Calibration Services

A thermometer measures temperature. Clocks track time. Hygrometers assess humidity levels. Odometers calculate distance traveled. Ohmmeters determine electrical resistance. These everyday instruments represent only a small fraction of the vast range of measuring tools used across countless industries and disciplines to quantify an extensive array of variables.

Meters, gauges, sensors, and other testing instruments are calibrated to standardized scales that assign quantitative values to the media being measured. These devices are essential across various industries, ensuring precise and reliable readings for standardized units of measurement.

To maintain accuracy and consistency, measuring instruments require calibration and periodic recalibration. Over time, environmental factors and regular use may cause an instrument to drift from its intended accuracy, impacting performance and reliability. Calibration services are available to test, adjust, and restore instruments to their correct operating parameters, ensuring continued precision for their designated applications.

The History Of Calibration

The practice of measurement dates back nearly as far as humankind, with the earliest objectives focused on quantifying weight and distance. Standardized lengths and weights provided the foundation for trade and commerce, allowing for fair and consistent exchanges.

The first recognized distance measurement was the cubit, defined as the length from a man's shoulder to the tip of his finger. However, this method lacked accuracy as it depended solely on the individual's size.

During his reign from 1100 to 1135, King Henry of England standardized the yard, declaring it as the distance from the tip of his nose to the tip of his outstretched thumb. This decision marked an early effort to bring uniformity to measurement.

In 1196, England established the Assize of Measures to standardize length measurements further. By 1215, the Magna Carta formally set standards for measuring wine and beer, reflecting the growing need for consistency in trade and industry.

The mercury barometer, invented in 1643 by Evangelista Torricelli, introduced a method for measuring atmospheric pressure. It was soon followed by the manometer, a water-filled tube that measured air pressure in inches, operating on similar principles.

In 1791, France introduced the metre, giving rise to the metric system, which was officially adopted in 1795. This system laid the groundwork for modern international measurement standards.

The word "calibrate" entered the English language during the American Civil War, though its origins are debated. Some argue it derives from the Latin "caliber", meaning steel, while others trace it to the Arabic "qualib", meaning mold, as in casting. Initially, calibration referred to the measurement of gun bores and bullets to ensure consistent ammunition and firing accuracy. During the 1860s, decades before the Industrial Revolution, only the most skilled forges and metal smiths handled this process.

With the Industrial Revolution, the need for consistency in materials, products, and delivery became paramount. More accurate scaling of quantity became essential in every aspect of measurement. As industry expanded, so did the development of more effective ways to quantify and standardize measurements into usable units.

By 1960, the metric system underwent modernization, establishing a worldwide standard of measurement that remains widely accepted today.

The oil crisis of the 1970s further accelerated the demand for economical transportation and environmentally conscious practices, leading to the rapid advancement of sophisticated testing equipment for an increasingly vast array of applications.

In the mid-1990s, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) were established to create global measurement and calibration standards, ensuring consistency across industries and applications.

The rise of the Computer Age introduced CAD (Computer-Aided Design) technology, which revolutionized measurement and manufacturing. Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) emerged as a method for translating symbols on engineering drawings into precise, computerized manufacturing instructions, ensuring accurate three-dimensional reproductions. Dimensioning defines the geometry of a theoretically perfect object, while tolerancing establishes the allowable variations in the form or size of the actual finished product.

With the continued advancement of environmental, manufacturing, and space exploration technology, the need for more precise measurement and calibration methods will remain a driving force in scientific and industrial progress.

What is Calibration?

Metrology, the science of measurement, establishes agreed-upon standards that facilitate fair trade and international commerce. Its impact extends across utilities, the environment, economics, healthcare, and manufacturing, directly influencing consumer confidence and ensuring consistency in product quality and safety.

Metrology is built upon three fundamental principles: defining a unit of measurement, realizing the measurement through instrumentation, and establishing traceability to a quantitative rating.

A unit of measure can represent various physical properties, such as temperature, time, or longitude. It may define distance, ranging from micrometers to light-years, or quantify mass, weight, volume, flow, and strength. Once a unit is clearly defined, it is placed on a quantifiable scale, allowing a rating to be applied. This rating is then compared to a standardized baseline, ensuring traceability and accuracy.

To guarantee reliable measurements, standardized instruments must be developed to precisely measure units, ensuring correct specifications while detecting defects, anomalies, or wear patterns. These instruments are calibrated to predetermined standards and are capable of identifying irregularities in the units being measured.

Since measurement accuracy is critical, the testing equipment itself must undergo routine verification to confirm that it continues to provide correct specifications. The scheduled timeframe for this verification process is referred to as the calibration interval. Additionally, if a calibration device is exposed to unusual environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, high humidity, or mechanical shock, it should undergo immediate recalibration to maintain accuracy and reliability.

Calibration Devices

- Load Cells

- Transducers that convert the acting force into an analog electrical signal that provides a reading of deformation. The load cell is calibrated by attaching a pre-standardized device that provides a separate reading from the transducer when the cell is loaded. If both readings are not the same, the load cell is adjusted and another reading is taken. This process may be repeated until the load cell is in precise calibration with the testing device.

- Because the load cell is typically an integrated part of a larger system, follow-on steps in the process may be exponentially affected by a mis-calibrated piece of equipment, causing catastrophic failure of the product or the line. Accurate readings provide traceable calibration to assure proper function of equipment and machinery.

- Instrument Calibration

- Used to adjust and maintain accurate readings from electronic measuring devices. The electronic signals are measured with calibration tools that are set to manufacturer's specifications. Electronic measuring devices that require periodic calibration include weighing scales, acoustic and vibration test equipment, lasers, industrial ovens, and speedometers.

- Strain Gauges

- A sensing element in a sensor. The most common consists of a resistive foil pattern on a backing material. When stress is applied to the foil, it will deform in a predetermined way. It is the main sensing element for a variety of sensors, including torque sensors, position sensors, pressure sensors, and force sensors.

- Data Acquisition

- Sensors can convert electronic signals into physical parameters which are assigned digital values. This process allows for the conversion of information into an electronic stream that provides fast, uninterrupted communication. The flow of the data, and the electricity that powers it, must be carefully regulated to avoid overloading the system.

Calibrating Through Sensors

Sensors can detect and record measurements of sound, vibration, and acoustics through the use of geophones, microphones, hydrophones, and seismometers.

- Chemical Sensors

- Can detect the presence or absence of substances in a liquid or gas. Carbon monoxide detectors and breathalyzers are common chemical sensors.

- Automotive Sensors

- Measure everything from oil, water, and air pressure to camshaft and crankshaft positions, wheel speed, engine coolant temperature, fuel level and pressure, and oil level and pressure. There are airbag sensors, mass air flow sensors, light sensors, and temperature sensors to ensure passenger comfort and safety.

- Proximity Sensors

- Can detect an undesired presence and set off an alarm if the presence crosses specified boundaries. These are most commonly found as motion-detecting lights and car alarms but can also apply to excessive moisture or sound levels.

Instruments that Calibrate

Instruments that measure elements of the environment provide information on moisture and humidity levels, temperature, air flow and quality, soil content, environmental conditions for flora and fauna, and tidal conditions.

There are instruments that read levels of radiation, ionization, and subatomic particles. These include Geiger counters, radon detectors, dosimeters, and ionization chambers.

Navigational instruments such as a compass, gyroscope, or altimeter are delicate tools that require frequent calibration to maintain accurate readings.

Gauges That Calibrate

- Optical Gauges

- Measuring instruments that may be sensors detecting, translating, and transmitting quantifiable levels of light, color, or heat into an image that can be read. Some optical gauges are scintillators, fiber-optic sensors, infrared sensors, LED sensors, photo switches, and photon counters.

- Temperature Gauges

- Not limited to a simple mercury or alcohol bulb thermometer, temperature measuring devices may include bimetal strips, calorimeters, flame detectors, thermocouples, or pyrometers.

Calibration Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

Calibration service aims to detect inaccuracies and uncertainties of measuring instruments or pieces of equipment.

Calibration service aims to detect inaccuracies and uncertainties of measuring instruments or pieces of equipment.

The International System of Units (SI system) is a standardized system of measurement, which goal is to communicate measurements precisely through a coherent and consistent expression of units describing the magnitudes of physical quantities.

The International System of Units (SI system) is a standardized system of measurement, which goal is to communicate measurements precisely through a coherent and consistent expression of units describing the magnitudes of physical quantities.

The goal of calibrating services are to minimize error and increase assurance of measurements.

The goal of calibrating services are to minimize error and increase assurance of measurements.

A universal calibrating machine main function is to calibate compression type instuments.

A universal calibrating machine main function is to calibate compression type instuments.

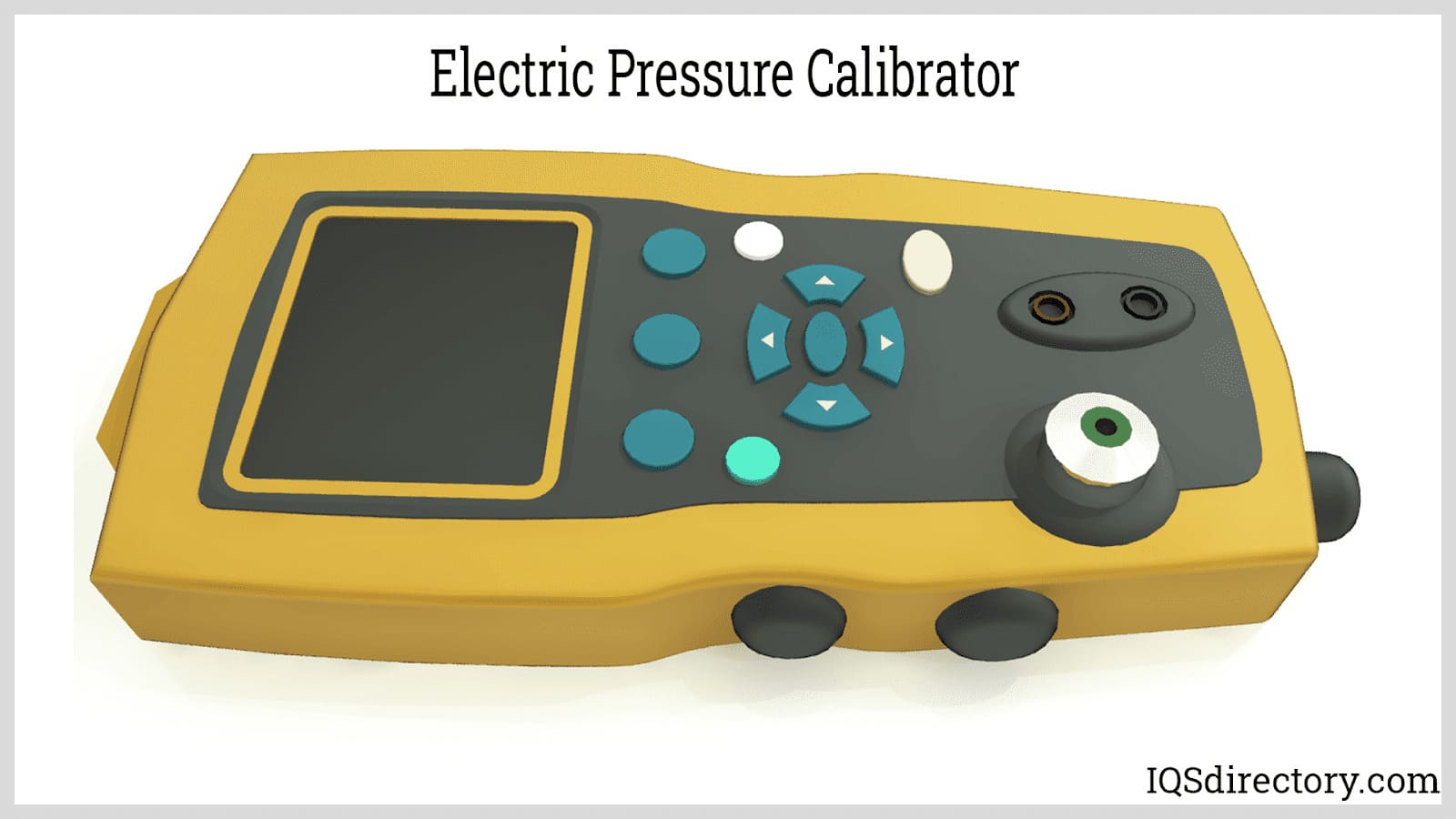

An example of a pressure calibrator which apply and control the pressure to a DUT.

<img data-cke-saved-src="https://www.iqsdirectory.com/articles/calibration-service/calibration-sticker.jpg" src="https://www.iqsdirectory.com/articles/calibration-service/calibration-sticker.jpg" alt="calibration sticker" title="Calibration" sticker"="">

A calibration sticker is attached to the equipment for verification of the calibration, which usually indicates the equipment serial number and the date of the next calibration.

An example of a pressure calibrator which apply and control the pressure to a DUT.

<img data-cke-saved-src="https://www.iqsdirectory.com/articles/calibration-service/calibration-sticker.jpg" src="https://www.iqsdirectory.com/articles/calibration-service/calibration-sticker.jpg" alt="calibration sticker" title="Calibration" sticker"="">

A calibration sticker is attached to the equipment for verification of the calibration, which usually indicates the equipment serial number and the date of the next calibration.

Types of Calibration

Calibration instruments may be handheld, portable, or fixed testing equipment. Handheld units are manually operated, compact devices that can be used in-house or for on-site calibration. Portable units are designed with carrying handles or wheels, allowing them to be moved to the equipment being calibrated. Fixed calibration stations are permanently mounted and provide the most accurate readings.

ISO IEC standards establish a baseline for the calibration of all measuring devices. The specific calibration process required depends on the type of testing equipment being calibrated.

Calibration services provide test facilities, equipment, or maintenance for systems already in use. A good service provider will offer guidance and information on ISO IEC standards relevant to the calibration process.

- Electrical Calibration

- Measures time, voltage, current, resistance, inductance, capacitance, radio frequency (RF), and power to ensure the accuracy of electrical instruments.

- Dimensional Calibration

- Uses tools and gauges such as dial indicators, calipers, micrometers, and dial indicators to measure physical dimensions and ensure precision.

- Mechanical Calibration

- Evaluates weight, tension, compression, and torque, ensuring that mechanical instruments provide accurate force and load readings.

- Physical Calibration

- Uses advanced equipment to measure temperature, humidity, vacuum, and pressure in a controlled environment. This process involves air, hydraulic, dial, and digital gauges, as well as high-accuracy pressure calibration.

- Equipment Calibration

- The process of adjusting pieces of equipment to ensure precision and consistency in measurements.

- Hardness Tests

- Assess the hardness and tensile strength of materials, determining their resistance to deformation and mechanical stress.

- Machine Calibration

- Adjusts machinery to meet established standards, improving accuracy and precision in operations.

- Pipette Calibration

- Verifies that pipettes accurately contain and dispense precise volumes of fluid, ensuring reliability in laboratory and industrial applications.

- Torque Wrench Calibration

- Ensures that torque wrenches apply the correct amount of force, allowing users to achieve proper fastening and tightening with precise measurements.

Industries that Use Calibration Services

The automotive industry is one of the most diverse users of calibration instruments, relying on precise measurement tools throughout design, manufacturing, and testing. Developing and producing automobiles requires the measurement of aerodynamics, weight, pressure, stress, strain, shear, torque, force, speed, electricity, comfort, fuel economy, environmental impact, load capacities, intake, and exhaust, among many other factors. The tools used to measure these values range from small, handheld gauges to large-scale wind tunnels and multi-mile test tracks, each playing a crucial role in vehicle development and performance validation.

Beyond automotive applications, calibrated measuring instruments are essential across a broad spectrum of industries, including electronics, aerospace, aeronautics, meteorology, construction, manufacturing, food service, medical, energy, and entertainment. Each industry relies on different types of measurement devices, tailored to their specific requirements. These instruments can measure time, distance, light, sound, air movement, temperature, electronic impedance, data acquisition, component strength, material composition, and pressure. The accuracy of these measurements ensures product reliability, regulatory compliance, and safety across all sectors.

Calibration Services Terms

- Accuracy

- A defined tolerance limit that establishes the allowable deviation between the measured output of a device and the true value of the quantity being measured. Ensuring high accuracy is crucial for reliable data collection and maintaining precision in various applications.

- Alignment

- The process of making precise adjustments to a device or system to bring it into proper operational condition. Proper alignment ensures optimal performance, reduces wear and tear, and improves measurement consistency.

- Analog Measurement

- A measurement system that generates a continuous output signal corresponding to the internal input. Unlike digital measurements, which produce discrete values, analog measurement provides smooth, uninterrupted readings that reflect real-time changes in the measured parameter.

- Axial Strain

- A type of deformation that occurs along the same axis as the applied force or load. It measures how much an object stretches or compresses in the direction of the force, providing insight into its structural integrity and performance under stress.

- Calibration Curve

- A graphical representation that compares the output of a measurement device to a set of known standard values. This curve helps determine the accuracy of an instrument and assists in making necessary adjustments to ensure precise readings.

- Calibration Laboratories

- Specialized facilities or companies that provide professional calibration services for instruments, gauges, and sensors. These laboratories use highly accurate reference standards to verify and adjust measurement devices, ensuring compliance with industry regulations and quality control requirements.

- Capacitor

- An electronic component that stores and releases electrical energy in a circuit. Capacitors are used to regulate voltage, filter signals, and store energy for short-term power supply needs in various electrical and electronic applications.

- Compensation

- A method of correcting or minimizing known errors in a measurement system by using specially designed devices, materials, or computational techniques. Compensation enhances the accuracy and reliability of readings by counteracting the effects of external influences such as temperature changes, mechanical stress, or electrical interference.

- Equilibrium

- A stable condition in which all opposing forces or influences are balanced, preventing any net change in the system. Equilibrium is essential in physics, engineering, and chemistry, ensuring that processes function predictably and efficiently.

- Fatigue Limit

- The maximum amount of cyclic stress or strain that a material can endure without experiencing structural failure over an extended period. Knowing the fatigue limit of a material helps engineers design durable and long-lasting components for mechanical systems and structures.

- Hertz (Hz)

- A unit of frequency that measures the number of cycles or oscillations per second in a periodic waveform. Hertz is commonly used in the study of electrical signals, sound waves, and electromagnetic radiation to determine signal properties and behavior.

- K-Factor

- A value that represents the harmonic content of an electrical load current and its impact on a power source. The K-factor helps engineers assess the safe operating limits of electrical systems, reducing the risk of overheating and inefficiencies caused by harmonic distortion.

- Mean Stress

- The average stress level in a material subjected to repeated loading and unloading cycles. Mean stress is crucial in fatigue analysis, helping engineers predict how long a material can withstand repeated stress variations before failing.

- Metrology

- The scientific study of measurement, including the development of standards, methods, and instruments used for accurate quantification of physical properties. Metrology ensures consistency, reliability, and compliance with industry regulations across various fields, including manufacturing, healthcare, and research.

- Nonlinearity

- A condition in which the relationship between the input and output of a system deviates from a straight-line proportional response. In calibration, nonlinearity is expressed as the maximum deviation of a device’s output from an ideal linear response and is usually given as a percentage of the full-scale measurement range.

- Output

- The measurable result or signal generated by an instrument, sensor, or system in response to an input stimulus. The accuracy and stability of the output are critical in ensuring reliable data collection and process control in industrial, scientific, and electronic applications.

- Range

- The span of values over which a measuring instrument or sensor can provide accurate readings without exceeding its operational limits. The range defines the minimum and maximum values that a device can effectively measure while maintaining precision and reliability.

- Resistor

- An electrical component that introduces resistance into a circuit to control current flow and voltage levels. Resistors play a crucial role in regulating electrical signals, preventing overloading, and shaping circuit behavior in electronic devices and power systems.

- Resolution

- The smallest detectable change in the measured value that an instrument can register. Higher resolution allows for finer measurement distinctions, making it essential in applications requiring extreme precision, such as scientific research, medical diagnostics, and high-tech manufacturing.

- Torque

- A measure of the rotational force applied to an object around an axis, determining its ability to rotate or twist. Torque is fundamental in mechanical systems, automotive engineering, and industrial machinery, influencing the performance and efficiency of engines, motors, and drive systems.