Chillers

Liquid chillers rapidly cool large volumes of refrigerant to efficiently extract heat from air or other liquids, then circulate the cooled fluid or air as required.

Chillers FAQs

What is the main function of a liquid chiller?

A liquid chiller removes heat from air or other liquids by circulating refrigerant through a sealed system. The cooled fluid or air is then circulated to maintain stable temperatures for industrial processes or facility cooling.

How do industrial chillers work?

Industrial chillers rely on a continuous refrigeration cycle. The refrigerant absorbs heat, moves it away, and releases it into the atmosphere through a condenser, maintaining efficient temperature control and system stability.

What are the main components of a chiller system?

A typical chiller includes a compressor, condenser, evaporator, expansion valve, and refrigerant. These components work together to absorb heat, compress and condense the refrigerant, and regulate cooling flow for stable operation.

What are the benefits of using chillers in manufacturing?

Chillers improve efficiency by providing rapid, consistent cooling for machinery and materials. They help prevent overheating, reduce energy waste, and ensure product quality, making them essential in manufacturing and processing environments.

What is the difference between air-cooled and water-cooled chillers?

Air-cooled chillers use ambient air to condense refrigerant, while water-cooled chillers use water circulated through cooling towers. Air-cooled models are easier to install, whereas water-cooled systems offer higher efficiency in large facilities.

How do glycol chillers benefit food and beverage applications?

Glycol chillers use a glycol-water mixture to achieve low temperatures ideal for cooling beverages and food products. They help maintain flavor, clarity, and freshness while meeting strict food safety requirements in production environments.

What factors should be considered when selecting a chiller?

Choosing a chiller involves evaluating cooling capacity, refrigerant type, power source, space, and operational needs. Proper selection ensures efficiency, compliance with safety standards, and compatibility with the facility’s existing infrastructure.

Why are modern chillers important for industrial facilities?

Modern chillers provide precise temperature regulation essential for process stability, energy efficiency, and equipment longevity. They support operations in manufacturing, medicine, and power generation by preventing downtime and improving reliability.

A History of Chillers

Chiller technology shares its origins with air conditioning, as both rely on the same fundamental principles of heat transfer. In the 18th century, scientists such as Benjamin Franklin explored how liquid refrigerants could be used to cool air and other liquids, laying the foundation for modern cooling systems. These early experiments revealed that certain liquids could absorb heat efficiently, lowering air temperature and setting the stage for future advancements.

The breakthrough in mechanical air conditioning came in 1902 when Willis Carrier developed the first self-contained system. He discovered that heating air reduces relative humidity, allowing it to absorb moisture, while cooling air extracts heat and humidity, creating a more controlled environment. This two-step process became the cornerstone of modern chiller technology, enabling precise temperature regulation across industries.

As demand for efficient cooling solutions grew, scientists sought more effective refrigerants. In 1931, they identified Freon as a superior alternative to water or air alone due to its enhanced cooling properties. By 1938, Trane introduced a fully enclosed refrigerant-based system with a compressor, condenser, and evaporator—components still integral to today’s industrial chillers. The 1950s saw the plastics industry adopt chillers to improve product quality, fueling the widespread use of plastic in consumer and industrial applications.

By the late 20th century, chiller technology had become essential across a broad range of industries, from glass manufacturing to power generation. These systems played a vital role in supporting industrial expansion and even helped sustain the digital age by enabling more reliable electrical grids. Today, chillers are an indispensable part of modern infrastructure, ensuring temperature control in critical applications worldwide.

Benefits of Using Chillers

While some operations may function without liquid chillers, these systems provide undeniable advantages in efficiency, space utilization, temperature control, and cost savings.

Cooling Speed of Chillers

Industrial chillers excel at quickly lowering the temperature of large volumes of materials, outperforming other cooling methods in both speed and reliability.

Space Saving of Chillers

Unlike ice or chemical-based cooling systems, chillers require less space and operate with greater efficiency. Their compact design allows businesses to allocate a dedicated area for cooling without disrupting workflow, ensuring consistent temperature regulation without unnecessary bulk.

Predictable Cooling Temperature in Chillers

Other cooling methods can create uneven temperature distribution, leading to product inconsistencies or potential damage. Industrial chillers maintain stable and uniform cooling, preventing hot spots and ensuring product integrity.

Chiller Cost Savings

Compared to alternative cooling solutions, chillers offer a more cost-effective approach by reducing waste, improving energy efficiency, and minimizing ongoing maintenance expenses.

How Chillers Work

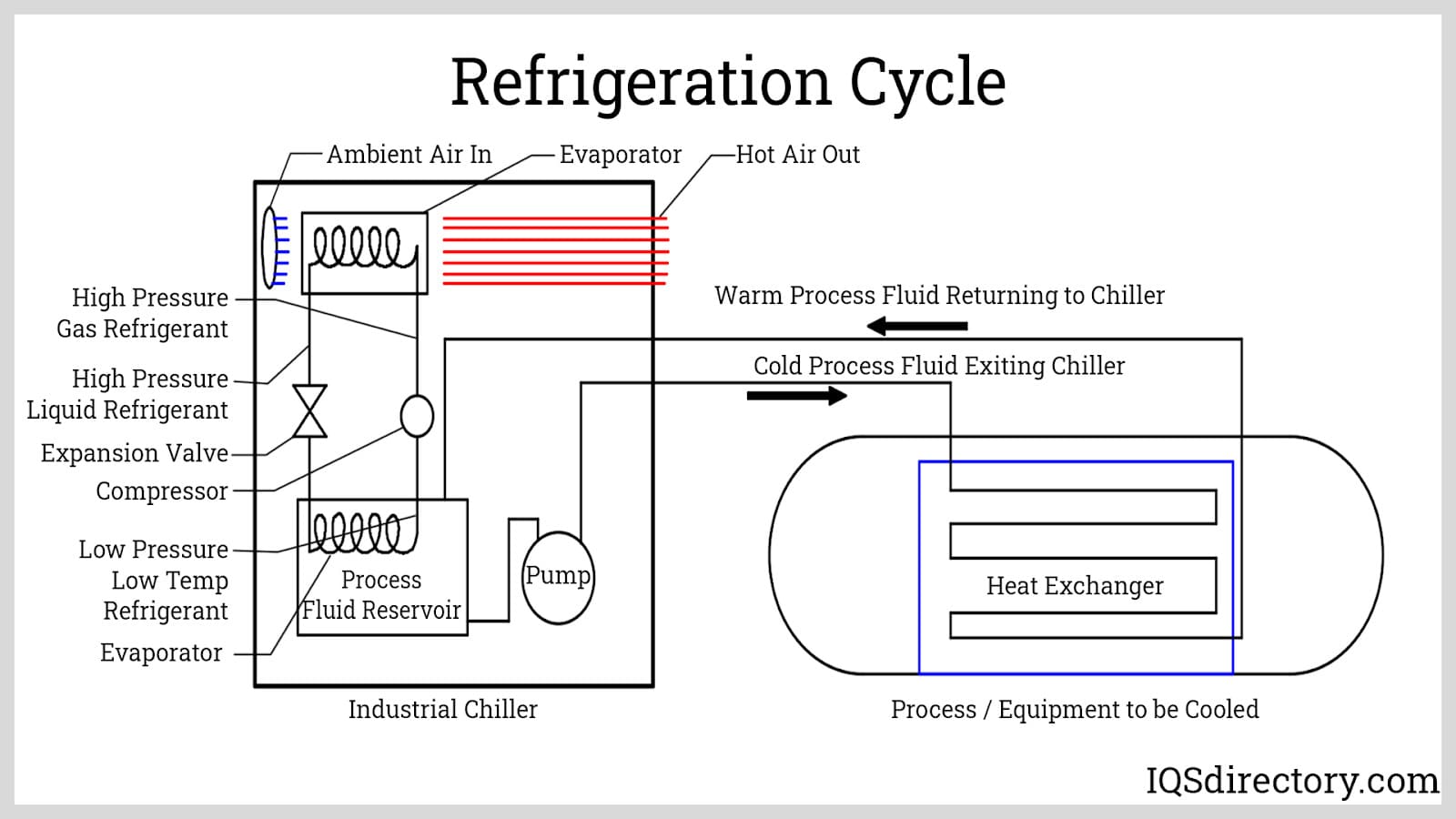

Modern liquid chillers rely on a continuous cycle of heat transfer, driven by the movement of liquid refrigerant through a sealed system. As refrigerant circulates, it absorbs heat from air or water, transports it away, and then safely releases the excess heat into the atmosphere. This controlled process ensures efficient cooling while maintaining system stability.

To sustain this cycle, chillers must keep refrigerant contained within durable pipes and mechanisms capable of withstanding high temperatures and pressure. Specialized refrigerants like Freon enhance efficiency due to their unique thermal properties—they boil at lower temperatures than water while freezing at higher temperatures than ice. This narrow operational range optimizes heat exchange, enabling faster and more effective cooling of air or water.

Parts of a Chiller

While chiller designs vary, all systems share essential components that work together to regulate temperature efficiently.

Chiller Condenser

The condenser rapidly cools heated refrigerant, converting it back into a liquid to restart the cooling cycle. Depending on the chiller type, condensers may be air-cooled, water-cooled, or evaporation-cooled to optimize efficiency and performance.

Compressor in a Chiller

By applying extreme pressure, the compressor prepares the refrigerant to absorb heat effectively. The type of compressor varies based on chiller design. For example, screw chillers use twin rotary screws to maintain continuous, high-speed operation with a smoother, more consistent flow than other motorized compression methods.

Chiller Evaporator

This critical component cools liquid by allowing highly pressurized refrigerant to undergo a phase change. As the refrigerant transitions, it reaches extremely low temperatures, drawing heat from the surrounding liquid and enabling efficient cooling.

Chiller Refrigerant

Different chillers utilize various refrigerants, often blended for optimal performance. Due to environmental regulations, refrigerants are carefully controlled to prevent leaks and ensure safe operation. Chiller maintenance may involve topping off or replacing refrigerants to maintain efficiency and compliance.

Expansion Valve of a Chiller

Regulating the refrigerant flow, the expansion valve responds to both actual and target temperatures. In industrial chillers, this valve can trigger a chain reaction by increasing refrigerant flow as cooling progresses. As the refrigerant absorbs heat, the expansion valve introduces additional coolant, accelerating the cooling process.

Vents and Cooling Towers

Efficient heat dissipation is essential for all cooling systems. Industrial chillers, handling large liquid volumes measured in tons, often incorporate external cooling towers to expel excess heat, maintaining system stability and efficiency.

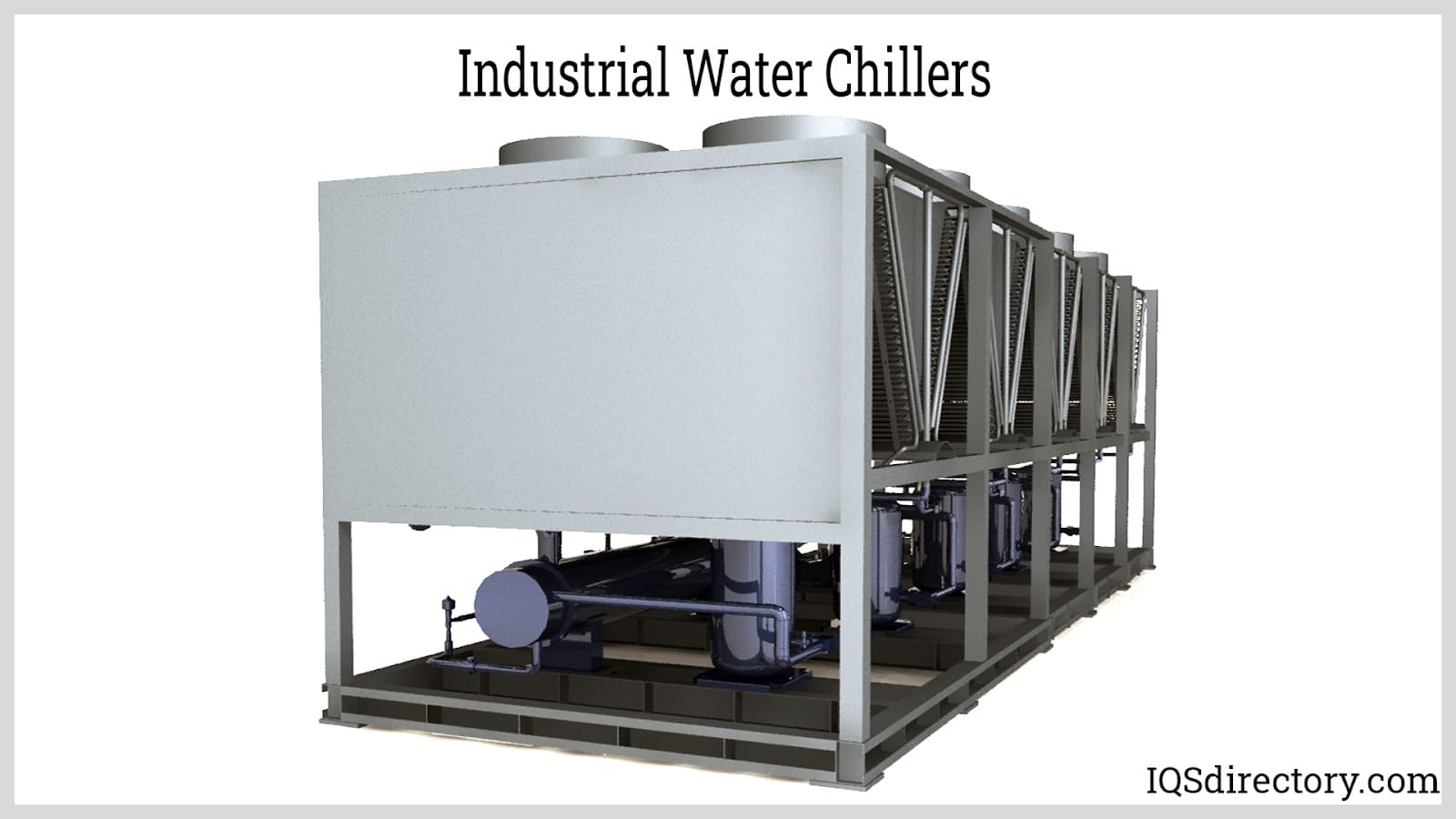

Chiller Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

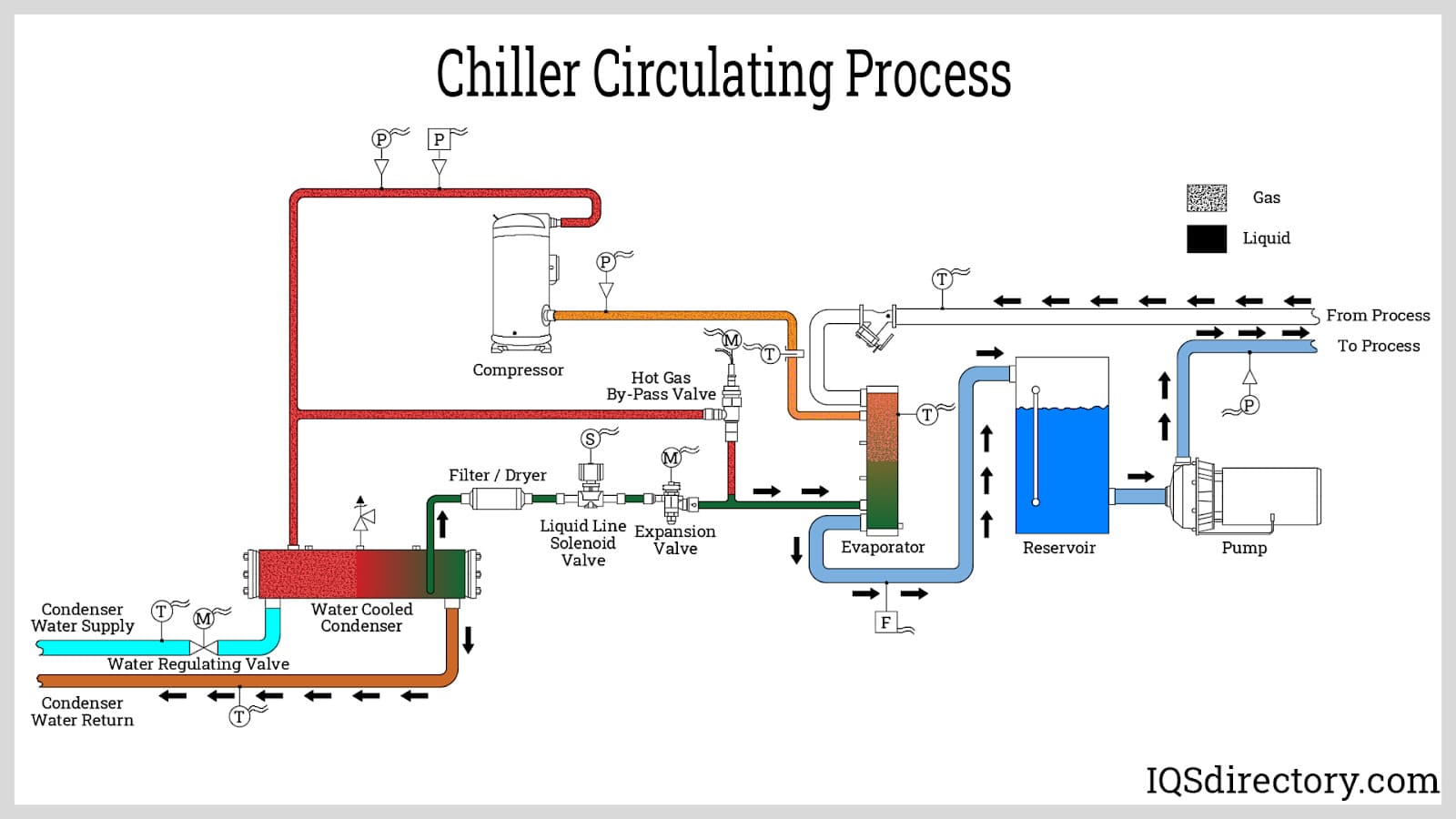

Chillers removes heat by circulating heat-absorbing a refrigerant through a series of mechanisms which releases the heat.

All chillers are designed to transform the refrigerant from a liquid to a vapor and back to a liquid, while in vapor form the refrigerant removes the heat from a process.

Industrial chillers circulates cooled liquid through equipment in order to maintain efficiency and productivity.

Glycol chiller uses a percentage of glycol mixed with water to create extremely low temperatures.

Laser coolers uses a multi-process that includes techniques in which atomic and molecular samples are cooled down to near absolute zero.

Air cooled chillers uses cool fluids that works in tandem with the air handler system and rely on fans to reject outside heat rather than relying on cooling towers.

Water chillers uses water as a secondary refrigerant.

Centrifugal chiller uses compression to convert kinetic energy into static energy to increase the refrigerant pressure and temperature.

Chiller Types

Absorption Chillers

Unlike traditional chillers that rely on electricity for compression, absorption chillers use heat from combustion or hot water to drive the cooling process. While they follow the same fundamental cycle of evaporator, compressor, and condenser, the compression stage operates through a chemical absorption process rather than mechanical means.

During compression, chilled water flows into the system and absorbs heat within a heat exchanger. The refrigerant, mixed with a chemical absorbent, passes through the heat exchanger before advancing to the next phase of the cycle. Once heat transfer is complete, the cooled water exits the system. Meanwhile, heated water or a combustible fuel source, such as natural gas, enters the generator at the condenser stage to sustain the cycle. Due to their design, absorption chillers typically require large cooling towers to regulate water temperature and maintain efficiency in industrial applications.

Air Cooled Chillers

Air-cooled chillers use ambient air to condense the refrigerant during the cooling cycle, eliminating the need for water in the condensing process. As the most commonly used chiller type, they offer a reliable and efficient cooling solution for a wide range of applications. By dissipating heat directly into the surrounding air, these systems simplify installation and maintenance, making them a preferred choice for facilities without access to a steady water supply or where water conservation is a priority.

Blast Chillers

Blast chillers are specialized refrigeration units designed to rapidly cool food, preserving freshness and preventing bacterial growth. Commonly used in the catering and food service industries, these chillers lower food temperatures much faster than standard refrigeration, ensuring compliance with food safety regulations. Due to their advanced cooling capabilities, blast chillers are more costly to manufacture and are primarily found in commercial kitchens where efficiency and food quality are top priorities.

Brewery Chillers

Brewery chillers play a crucial role in beer production, particularly in cold crashing and fermentation. These systems circulate glycol at approximately 28°F to maintain beer at an optimal 33°F, ensuring proper temperature control throughout the brewing process. By precisely regulating cooling, brewery chillers help enhance flavor, clarity, and consistency in the final product.

Central Chilled Water Units

Central chilled water units are integral to large-scale air conditioning systems, using air handling units equipped with chilled water coils to regulate temperature. By distributing cooled water throughout a facility, these systems provide efficient climate control for commercial and industrial buildings, ensuring consistent and reliable cooling.

Centrifugal Chillers

Centrifugal chillers utilize a high-speed centrifugal compressor to drive the refrigeration cycle, making them ideal for large-scale cooling applications. Their design allows for efficient cooling with minimal energy consumption, making them a preferred choice for high-capacity industrial and commercial systems.

Chiller Systems

Chiller systems integrate multiple components to provide cooling for industrial processes or facility-wide temperature control. By working as a complete system, they optimize efficiency and ensure consistent cooling performance across various applications.

Cooling Systems

Cooling systems are designed to remove excess heat from an area, maintaining optimal temperatures for equipment, processes, or environmental comfort. These systems are essential in industries ranging from manufacturing to HVAC.

Dedicated-Process Chillers

Engineered for continuous, year-round operation, dedicated-process chillers provide precise, capacity-matched cooling for specialized applications. They are particularly suited for medical environments where maintaining stable temperature and water flow is critical for sensitive equipment and processes.

Evaporative Cooled Chillers

Though less common, evaporative-cooled chillers are among the most efficient liquid cooling solutions. By maintaining condensing temperatures between 85°F and 105°F, these chillers maximize energy efficiency while providing powerful cooling capabilities.

Fluid Chillers

Fluid chillers utilize a secondary cooling fluid to regulate temperatures in industrial processes. By circulating a controlled coolant, they enhance thermal management and improve efficiency in applications requiring precise temperature stability.

Glycol Chillers

Glycol chillers are refrigeration systems that circulate a glycol-water solution to cool various equipment and processes. Named for their use of glycol, a food-grade antifreeze, these chillers are widely used in the food and beverage industry, where maintaining precise and consistent cooling temperatures is essential for product quality and safety.

HVAC Chillers

HVAC chillers provide large-scale cooling for industrial and commercial environments. Often installed outdoors, these systems are available in both centralized and modular designs, allowing businesses to customize their cooling solutions for maximum efficiency and climate control.

Industrial Chillers

Industrial chillers are specialized refrigeration systems designed to cool liquids in manufacturing and processing environments. By regulating temperatures with precision, these chillers support a wide range of industrial applications, from plastics production to chemical processing, ensuring optimal performance, product quality, and energy efficiency.

Lab Chillers

Lab chillers are specialized refrigeration systems designed to maintain precise temperatures for laboratory equipment and sensitive materials. With a variety of models available, these chillers cater to different laboratory applications, ensuring that experiments and processes remain stable and temperature-controlled.

Liquid Chillers

Liquid chillers are refrigeration systems that effectively remove heat from various liquids, maintaining a stable temperature for industrial processes, cooling systems, and equipment. These chillers are essential in applications requiring consistent liquid cooling to preserve product quality or ensure operational efficiency.

Laser Chillers

Laser chillers are used to dissipate the heat generated by lasers and their components. By maintaining a consistent cooling flow, they prevent overheating, ensuring the laser system performs at its peak efficiency and prolongs the lifespan of sensitive components.

Liquid Coolers

Liquid coolers are recirculating chiller systems that operate within a closed-loop, continuously cycling the same refrigerant to maintain precise cooling. These systems ensure efficient temperature control while minimizing waste, making them ideal for applications that require consistent liquid cooling.

Machine Tool Chillers

Machine tool chillers regulate the temperature of coolant used in the cutting zone, ensuring precision and efficiency in machining operations. By recirculating coolant within a closed-loop system, these chillers help prevent overheating, extend tool life, and improve cutting accuracy.

Medical Chillers

Designed for critical applications, medical chillers feature high-pressure pumping, precise temperature stability, and advanced microprocessor controls. These self-contained systems ensure reliable cooling for sensitive medical equipment, such as MRI machines, CT scanners, and laser systems.

Portable Chillers

Portable chillers are self-contained cooling units designed for small-scale or dedicated applications. Their compact design allows for flexible placement and easy relocation, making them an ideal solution for situations where mobility and targeted cooling are essential.

Process Chillers

Process chillers are specialized cooling systems designed to regulate temperatures in industrial manufacturing and laboratory applications. Unlike HVAC chillers, which focus on air conditioning, process chillers cool materials and machinery, often handling large volumes of refrigerant at a time. Typically absorption-based, these systems feature high-quality stainless steel components to withstand extreme pressures and continuous operation. Their robust evaporators, compressors, and condensers ensure durability and efficiency in demanding industrial environments.

Recirculating Chillers

Recirculating chillers continuously circulate coolant within a closed-loop system, maintaining high efficiency while eliminating water waste. By reusing the same coolant, these systems ensure consistent temperature control for precision cooling applications in laboratories, industrial processes, and medical settings.

Screw Chillers

Screw chillers utilize a rotary screw compressor to drive the refrigeration cycle, offering reliable and efficient cooling. Known for their smooth operation and continuous high-speed performance, these chillers are ideal for applications requiring consistent and powerful temperature regulation.

Water Chillers

Water chillers are self-contained units that integrate a compressor, condenser, and chiller with internal piping and controls. These systems follow the standard refrigeration cycle but cool water instead of air, circulating it through an external piping system. Water chillers can include air- or water-cooled condensers and must be carefully designed to fit within existing structures for optimal performance and efficiency.

Vapor Compressors

Vapor compressors operate using a mechanical compression system to vaporize liquid refrigerant for cooling. This method efficiently moves high volumes of refrigerant through the evaporator, compressor, and condenser, allowing for rapid temperature reduction. Ideal for smaller operations or spaces where storing large quantities of coolant is impractical, vapor compressors deliver effective cooling for a variety of industrial and commercial applications.

Industry Uses for Chillers

The effectiveness of a chiller depends on the specific needs of each industry. Manufacturing facilities, for example, rely heavily on process chillers to prevent machinery from overheating. Selecting the right chiller requires careful consideration of available space, power supply, and operational demands. While some chillers operate only as needed, others, such as water chillers supplying a building’s cooling system, must run continuously.

Many industries integrate chillers into their daily operations, ensuring efficiency, safety, and reliability.

Uses in Manufacturing

Manufacturers, particularly in the plastics industry, depend on industrial-grade process chillers to remove excess heat from materials during production. Without chillers, many processes would require frequent pauses for air cooling, significantly reducing efficiency and output.

Uses in Food and Beverage

Strict federal regulations govern the storage and production of consumable goods. Chillers provide stable, uniform cooling to preserve ingredients and finished products. Process chillers can rapidly flash-freeze large quantities without compromising moisture content or altering ingredients, ensuring product quality and safety.

Power Generation Industry Uses

Power plants generate immense amounts of heat while producing electricity. Process chillers play a critical role in dissipating excess heat, allowing plants to maximize energy output within limited space. Without efficient cooling systems, modern power grids would struggle to sustain demand.

Chillers in Medicine

In the medical field, chillers support both equipment and storage needs. MRI machines and other advanced imaging devices produce significant heat during operation, requiring precise cooling to prevent overheating. Additionally, liquid chillers ensure the proper storage of temperature-sensitive medical supplies, preserving their integrity and effectiveness.

How to Custom Design Chillers

Every business has unique requirements when it comes to chiller technology. As with any large equipment, space considerations play a crucial role in system design. Chillers that connect to piping for water cooling or temperature regulation must be integrated seamlessly into the overall infrastructure. Factors such as coolant volume, power source, chiller size, and the selection of compressor and evaporator types can all be tailored to fit specific operational demands.

Planning for the future is key when designing a custom chiller system. Modular liquid chillers offer flexibility, allowing businesses to expand or relocate cooling systems as needed. Meanwhile, larger, stationary models provide robust cooling capacity with the ability to cycle on and off based on demand. The ideal custom chiller balances present operational needs with the ability to adapt to future growth, ensuring long-term efficiency and reliability.

Standards and Specifications for Safety With Chillers

The use of chiller technology is often regulated by local and federal laws, particularly in industries such as food, beverage, and medicine, where precise cooling is essential for product safety. Inconsistent temperature control can lead to contamination and product loss in various sectors, including plastics manufacturing. Additionally, refrigerant leaks pose serious health and environmental risks, which is why regulations typically require that chiller installation, service, and maintenance be handled by licensed professionals equipped to manage liquid refrigerants safely.

When selecting and installing a chiller system, several critical factors must be considered. The foremost concern is cooling capacity, which is measured in tons—where one ton is equivalent to the heat of fusion of one ton of ice, or 12,000 Btu/h. Chiller capacities range from small portable chillers to large-scale, multi-unit plants capable of handling thousands of tons of cooling demand.

Another important decision is the choice of refrigerant, which depends on the temperature range required for the application. Common refrigerants include water, ammonia, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, alcohol, brine, and methane. While fluorocarbons—especially chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—were once widely used, they have been largely phased out due to their harmful effects on the ozone layer.

Additional specifications to evaluate include condenser and evaporator flow rates, power source, cooling efficiency, system location, compressor type, and compressor horsepower. Most modern chillers are also equipped with local and/or remote control panels featuring temperature and pressure indicators, emergency alarms, and automated safety functions. When properly configured, chiller systems provide reliable and efficient cooling solutions for a wide range of industrial and process applications.

Things to Consider When Purchasing a Chiller

Chiller Expense and Your Bottom Line

Chillers represent a significant investment for any manufacturing or industrial facility, and cooling operations often consume a substantial amount of energy. However, advancements in chiller technology continue to improve energy efficiency, reducing both operational costs and environmental impact.

Many businesses underestimate the financial benefits of upgrading to a modern chiller system. One San Francisco company, for example, saved over $1.3 million annually after replacing outdated absorption chillers with new, energy-efficient electric chillers. Additionally, upgrading their chilled water distribution system reduced maintenance costs by over $100,000 per year, allowing the company to recoup its investment in less than six years.

While initial installation costs may seem high, focusing solely on short-term savings can lead to greater expenses in the long run. Businesses that take a forward-thinking approach to chiller investments can redirect utility savings toward operational improvements and increased profitability. As demonstrated by the San Francisco case, a well-planned chiller upgrade can generate lasting financial and operational benefits.

Finding the Right Chiller Manufacturer

Selecting the right chiller manufacturer is essential to ensuring long-term reliability and efficiency. A high-quality manufacturer should possess extensive expertise in temperature control and hold certifications for handling industrial-grade refrigerants. Since industrial chillers are long-term investments, businesses should choose a supplier with a proven track record of performance and support.

Industry Knowledge

A reliable chiller manufacturer understands the specific cooling requirements of different industries. For example, manufacturers supplying chillers for medical applications must be knowledgeable about strict temperature control requirements for laboratory and research facilities. The best manufacturers align their expertise with the operational needs of their customers to provide tailored solutions.

Working Relationship With a Chiller Manufacturer

Chiller manufacturers should act as long-term partners, offering valuable insights and recommendations for custom configurations that match a business’s unique cooling demands. A strong working relationship built on mutual respect and understanding allows businesses to maximize the benefits of their chiller investment, ensuring efficiency, reliability, and ongoing support as needs evolve.

Chiller Terms

Ambient

The surrounding environment, including temperature, pressure, and humidity, that interacts with a system or component.

Brine

A mineralized water solution containing sodium chloride, metallic elements, and/or organic contaminants.

British Thermal Units (BTU)

A unit of heat measurement representing the energy required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit.

Capillary Tube

A narrow tube between the condenser and evaporator that regulates refrigerant flow.

Central Chilling System

A self-contained chiller system consisting of multiple units and compressors but lacking a pump tank set.

Chlorofluorocarbon (CFC)

A refrigerant gas composed of chlorine, fluorine, and carbon. CFCs have been largely phased out due to their ozone-depleting effects.

Coefficient of Performance (COP)

A measure of a refrigeration system’s efficiency, calculated by dividing cooling output by heat input, expressed in BTU/hr.

Compressor

A device that increases refrigerant pressure, converting vaporized refrigerant into a high-pressure gas suitable for liquefaction in the condenser.

Condenser

A component that removes heat from the refrigerant, transforming high-pressure gas back into a liquid using forced air, water coils, or other cooling methods.

Control Center

The main control unit where the refrigeration system is operated and maintained.

Coolant

A liquid used to absorb and remove heat.

Energy Efficiency Rating (EER)

A measurement of a cooling system’s efficiency, calculated by dividing the system’s BTU output by its wattage.

Evaporator

A component where refrigerant absorbs heat, boils, and transitions into a vapor to facilitate cooling.

Expansion Valve

A device located between the evaporator and condenser that regulates refrigerant flow into the evaporator, controlling its temperature.

Filter Drier

A component that removes moisture and contaminants from vaporized refrigerants.

Heat Exchanger

A system that transfers heat from one fluid to another without mixing them.

Hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC)

A refrigerant composed of chlorine, fluorine, carbon, and hydrogen. HCFCs have lower ozone depletion potential than CFCs.

Hydrofluorocarbon (HFC)

A chlorine-free refrigerant that replaces CFCs and HCFCs, with no impact on the ozone layer.

Laser Cooling

A method that uses light to cool atoms to extremely low temperatures.

Ozone

A molecule composed of three oxygen atoms that absorbs ultraviolet radiation in the stratosphere but can contribute to smog and respiratory issues at ground level.

Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP)

A measurement of a substance’s impact on the ozone layer compared to CFC-11, which has an ODP of 1.

Ozone Layer

A protective layer in the stratosphere, located 12-30 miles above sea level, that absorbs harmful ultraviolet radiation.

Receiver

A storage vessel for condensed liquid refrigerant.

Refrigerants

Liquids that generate cooling effects through evaporation.

Refrigeration Ton

A unit equal to 12,000 BTUs, representing the cooling capacity of a chiller.

Sight Glass

A viewing window in a refrigeration system that allows operators to observe the refrigerant flow and system operation.

Solenoid Valve

A mechanism that controls refrigerant flow, particularly into the expansion valve.

Total Equivalent Warming Impact (TEWI)

The total amount of carbon dioxide emissions a refrigeration system produces throughout its operational lifetime.