Electric Hoists

Hoists are essential for lifting, lowering, and transporting goods and materials in industrial environments where conveyor systems or crane are impractical or ineffective. They use a cable, rope, or chain in combination with a pulley or pulley system to provide the necessary lifting force. Hoists can be operated manually or powered by pneumatic, hydraulic, or electrical sources.

While hoist systems are most commonly associated with elevators, they have widespread use across various industries, including automotive, paper, mining, forestry, oil and gas, shipbuilding, energy, and nuclear sectors.

Hoists in pharmaceutical settings may need to handle very heavy loads in clean room environments. Those in food service applications must comply with strict sanitary standards to ensure safe food handling. Hoists used in production environments might need to endure extreme temperatures, hazardous conditions, or continuous heavy-duty use. Additionally, some hoists are explosion-proof, making them suitable for environments where flammable materials are present.

The History of Electrical Hoists

-

Early Hoist Creation

As far back as 1480, Leonardo da Vinci designed a simple hoist, consisting of a large wheel attached to a windlass wound with rope. When the wheel turned, it either fed out or took up the slack in the rope, thus raising or lowering a load—likely a bucket or container—for the purpose of lifting water from a well.

In 1556, Agricola’s De Re Metallica described mine hoists powered by water, manual labor, or animals, used to lift ore from deep mine shafts.

Hoists in the 1800s

In 1845, the "Flying Chair" was introduced by Gaetano Genovese. This was a bench seat suspended on ropes used to lift passengers.

A year later, Sir William Armstrong invented the hydraulic crane. By using water pressure to level the load and counterweights to raise and lower the crane, it was able to move cargo with more force than existing steam-powered cranes.

In 1852, the Otis Elevator brake was created to stop the elevator cab from falling in the event of a cable failure.

Thomas A. Weston’s invention of the differential pulley block, also known as the block and tackle, in 1854 revolutionized lifting. It allowed heavy loads to be lifted with minimal effort by using a rope looped around pulleys attached to an axle.

In 1876, Yale Lock Company acquired the patent for the differential pulley block and began its commercial production.

In the 1880s, Alton J. Shaw, a draftsman for Edwin P. Allis, began improving steam-driven cranes by incorporating three reversible electric motors, driving hoists, trolleys, and cranes from a single control point. By 1889, Shaw designed, manufactured, and sold over thirty different crane configurations.

The first electrically operated elevator was built in Germany in 1880 by Werner von Siemens. By 1895, Frank Sprague had designed and sold nearly 600 elevators, later selling his company to Otis.

Hoists in the 1900s

The early 1900s saw a surge in industrial growth, resulting in faster, safer, and more affordable lifting equipment. Cranes, hoists, and elevators became commonplace across industries.

In 1935, the first portable electric chain hoist was developed, followed by the lever-operated chain hoist, making hoisting equipment accessible to a wider range of industries.

World War II further fueled the need for hoisting equipment as small factories became more involved in the war effort, and hoists were produced rapidly.

Post-war industrial growth saw the development of electric wire rope monorail hoists, electric chain hoists, and ratchet lever hoists, further advancing manufacturing and production.

In the following two decades, the package hoist was introduced—a single, economical unit designed for lighter lifting duties and smaller projects, revolutionizing construction and manufacturing.

In the following two decades, the package hoist was introduced—a single, economical unit designed for lighter lifting duties and smaller projects, revolutionizing construction and manufacturing.

By the 1960s, built-up hoisting systems were integrated to handle large-scale heavy lifting tasks over extended periods. Though more expensive, these systems proved durable and easier to repair, driving further innovation in lifting technology.

Design of Electric Hoists

A manual chain hoist is a straightforward device that operates using two loops of chain. The hand chain is looped around a chain wheel, which has indentations designed to catch and pull a link of the chain as it rotates. The lifting mechanism consists of a cog wheel, axle, drive shaft, gears, and sprockets.

When the hand chain is pulled, it turns the axle, which drives the gears of various sizes. Larger gears rotate slowly but provide more lifting force, while smaller gears spin faster with less force. The lifting chain is wrapped around the gears in a double or triple loop to increase lifting capacity. As the hand chain is pulled, it turns the drive shaft, which in turn moves the larger gears, lifting or lowering the load attached to the hoist hook.

The hoist includes hooks for securing it to a ceiling or overhead monorail, as well as for suspending the load. Many manual chain hoists are equipped with a chain stopper or braking system to prevent the load from being dropped.

Manual chain hoists are slow but cost-effective and simple to operate, without requiring any power source.

Hoists can operate using either a chain or wire rope. Chains are typically made of links or rollers, while wire ropes consist of twisted wire strands. For the same load capacity, chain is heavier than wire rope. However, wire rope is limited in length by the size of the cable drum it is wound around, whereas chain hoists can use larger lift wheels, allowing the lift to travel a greater distance.

Both wire ropes and chains require lubrication, especially under continuous use or harsh conditions. Without proper maintenance or if excessive force is applied, wire rope can rust internally, while chains may become worn, stretched, or develop stress fractures. Wire rope is prone to snarling when not under load, while chain is heavier but less likely to tangle. Wire ropes are best used for lifting at speeds over sixty feet per minute, as they can cause fatigue-inducing resonance at higher speeds. Wire rope hoists can handle material weights up to eighty tons.

Electric hoists are available as portable units or overhead lift systems. Portable hoists are stand-alone, lightweight, and easy to transport, typically used for light to medium-duty tasks, lifting up to a few tons. Overhead hoist systems, mounted to ceilings, beams, or heavy-duty tracks, can handle heavier loads—up to five tons for chain hoists and up to eighty tons for wire rope hoists.

Hoist Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

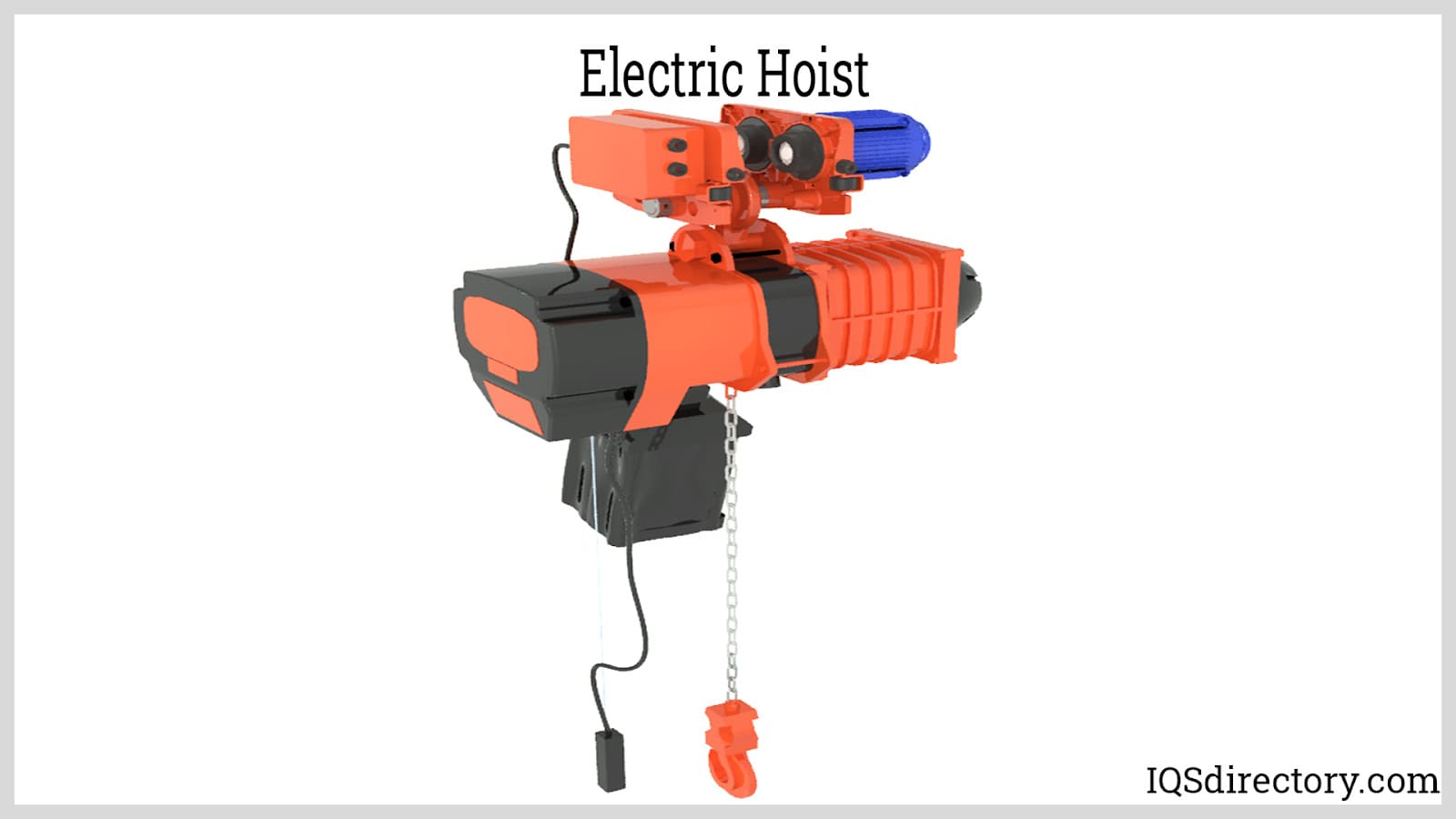

Electric hoists are handling equipment used for lifting, lowering, and transporting materials or products.

Electric hoists are handling equipment used for lifting, lowering, and transporting materials or products.

Manual chain hoists concentrate a low force with high travel input into a high force but its low travel output causes there slow operation.

Manual chain hoists concentrate a low force with high travel input into a high force but its low travel output causes there slow operation.

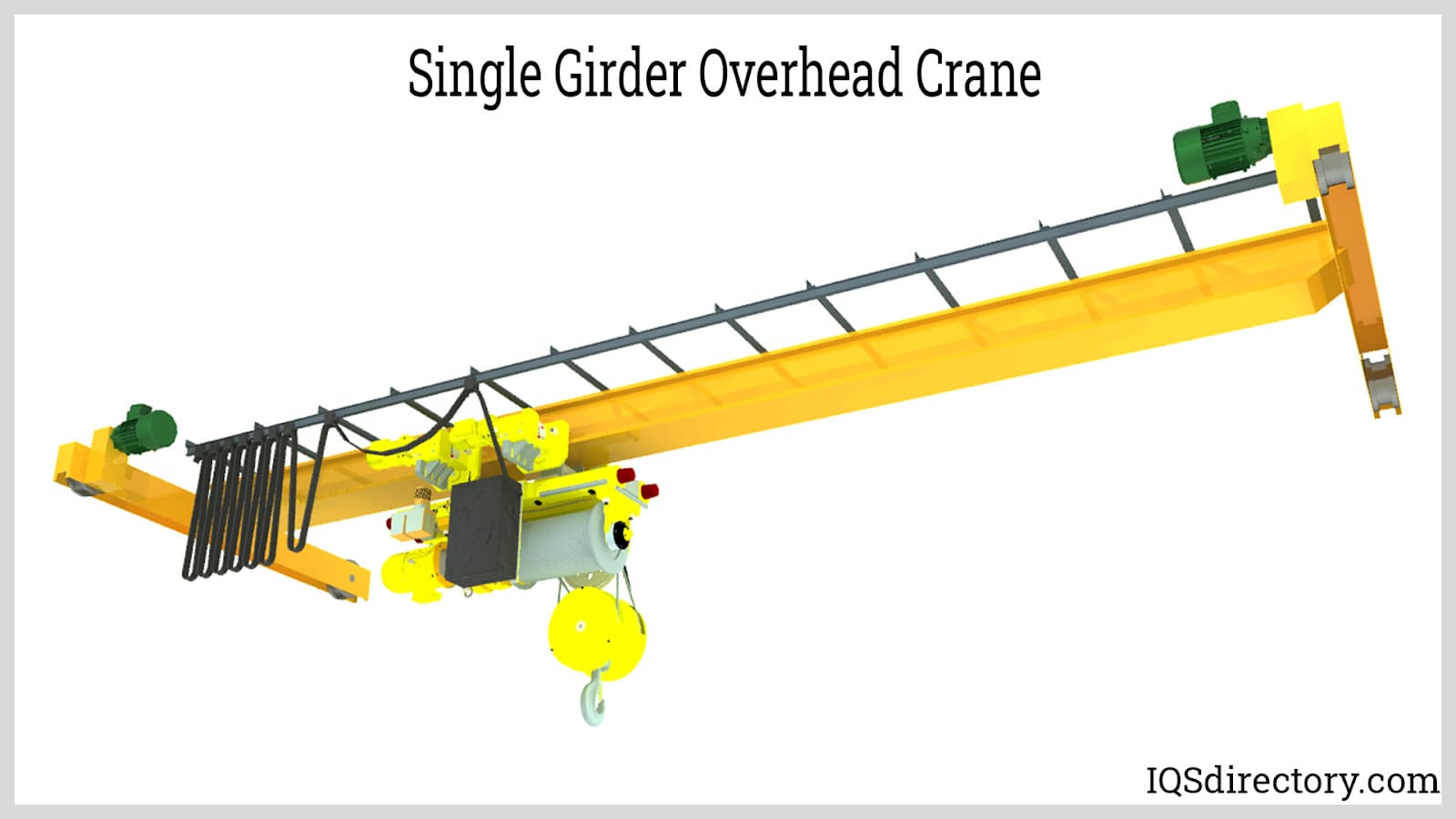

The bridge, are made up of beams and its structural frame is durable enough to support the combined load of the electric hoist and the lifted object.

The bridge, are made up of beams and its structural frame is durable enough to support the combined load of the electric hoist and the lifted object.

Electric travel trolleys have an electric motor to move the hoist a specific distance.

Electric travel trolleys have an electric motor to move the hoist a specific distance.

Electric hoists can be differentiated according to the type of suspension used and the position of the hoist.

Electric hoists can be differentiated according to the type of suspension used and the position of the hoist.

Hook-mounted hoists have a top hook that allows the attachment temporarily to a trolley or beam clamp.

Hook-mounted hoists have a top hook that allows the attachment temporarily to a trolley or beam clamp.

Overhead crane lift the heaviest loads at the highest lifting heights in an enclosed facility.

Overhead crane lift the heaviest loads at the highest lifting heights in an enclosed facility.

Jib cranes consist of a reach a horizontal beam where the electric hoist positions the load and a mast a vertical beam that supports the reach.

Jib cranes consist of a reach a horizontal beam where the electric hoist positions the load and a mast a vertical beam that supports the reach.

Types of Hoists

Hoisting systems can incorporate multiple hoisting devices to streamline production processes. The primary hoist may be an overhead trolley system that moves materials from one station to another.

Supplemental Hoists

Also known as auxiliary hoists, these are used to move lighter loads at faster speeds.

Trolley Hoists

Suspended by a hook attached to a track mounted overhead, trolley hoists lift the load and then move it to the next station for further processing.

Boat Hoists

These use a davit system to lift boats in and out of the water. Typically powered electrically or hydraulically, boat hoists can handle boats weighing up to ten tons.

Engine Hoists

Portable units, often mounted on wheels, these hoists are used in small shop environments and can be maneuvered easily.

Gate Hoists

Used in dam operations, gate hoists control the flow of water, allowing for precise adjustments to water levels.

Mini Hoists

These hoists are employed in placer and underground mining operations to move workers, equipment, and raw materials. In underground mining, mini hoists help create narrow shafts for deep mining, reducing the amount of excavation needed and minimizing disruption to the surrounding terrain.

Elevators

Elevators can be categorized as either rope-dependent or rope-free. Geared traction elevators are driven by a worm gear that uses steel ropes placed over a drive sheave, which is connected to a gearbox powered by a high-speed electric motor. These elevators are commonly used in settings where the car travels at up to 500 feet per minute.

Elevators are equipped with redundant safety systems, ensuring that the car won’t fall in the event of a failure. The cables are made from multiple intertwined strands of steel, and multiple rope loops hold each car, reducing the risk of complete cable failure.

Gearless Traction Elevators

These elevators operate with a low-speed, high-torque electric motor connected to the drive sheave. The cables, with counterweights on each end, are looped over the sheave, and the counterweights move in a separate shaft to balance the weight of the cab, requiring less power. Gearless traction elevators can travel at speeds up to 4,000 feet per minute.

Elevator Brake

This is activated by a governor if the car begins to move too quickly. The governor rope is looped around a sheave at the top of the shaft, and the counterweight balances the car's speed to prevent excessive dropping.

Electromagnetic Elevator Brakes

These brakes rely on electricity to keep the brake system in an open position. If there’s a power loss, the brakes close automatically, securing the car in place.

Auxiliary Hoists

These are used to handle lighter loads at higher speeds compared to the main hoist.

Boat Hoists

Hydraulically or electrically powered hoists designed specifically for lifting boats, capable of handling up to 20,000 pounds.

Car Hoists

Used in automotive maintenance and repair, these hoists raise vehicles so technicians can work on the tires or underbody.

Engine Lifts

Designed for lifting and safely transporting large engines within a facility.

Modular Hoists

These hoists feature an integrated drum, motor, and gearbox, with no visible shaft couplings between them, offering a more compact and efficient design.

Electric Hoist Manufacturers

A reliable electrical hoist manufacturer will tailor a system that aligns with your specific lifting requirements while ensuring compliance with state and federal health and safety regulations. The design process should address important factors such as the hoist's maximum weight capacity, lift speed, type of line, and mounting method. Inadequate or improperly designed equipment poses risks not only to materials but also to workers and machinery.

The hoist supplier will also develop a maintenance program that works seamlessly with your production schedule. This includes operator training, load testing, capacity certifications, inspections, and regular servicing of the equipment. The Overhead Alliance offers detailed guidelines for the design, manufacture, and safe use of cranes, elevators, and hoists.

Additionally, many companies provide 24/7 service with on-site repair, refurbishment, and replacement of faulty equipment, helping to minimize downtime and keep operations running smoothly.

Electric Hoist Terms

-

Attachments

Components used in conjunction with lifting devices, often forged, stamped, or cast.

Boom (Crane)

The extending part of a hoist, often connected to a rotating structure, responsible for supporting the hoisting tackle and the load.

Breaking Strength

The load required to break a chain or wire rope, indicating its strength limit.

Carbon Chain

A type of chain commonly used for various pulling and towing applications.

Clevis

A U-shaped fitting with one or more pins. A shackle clevis is used for safely lifting a load.

Controller

A device used by the hoist operator to control the power delivered to the hoist’s motor.

Critical Load

The load at which any uncontrolled movement of the hoist or load would result in hazardous conditions.

Critical Service

Using hoisting equipment to handle crucial or sensitive items.

Cushioned Start

A method for reducing the acceleration rate when moving loads to avoid sudden shocks or jerks.

Drum

A cylindrical barrel, either grooved or smooth, around which wire rope or chain is wound for operation and storage.

Festooning

A system for supplying power to a hoist moving along a beam, often involving a series of cables or chains.

Hook

A lifting attachment connected to the hoist, used to suspend the load.

Hook Load

The total weight supported by the hoist's hook, including the load, rope or chain tackle, and any other suspended mass.

Idler

A roller used to support and guide a rope or chain during the hoisting process.

Lifters

Grabs or devices designed to attach, hold, control, and direct loads, commonly used with hoists.

Line Speed

The speed at which the hoist winds or unwinds its lifting medium. This is usually measured without any load attached.

Load Capacity

The maximum weight a hoist is designed to safely lift. The line speed may decrease when operating at full capacity.

Pawl

A device that works with the ratchet to ensure the hoist only moves in one direction, providing safety if the lifting force is suddenly removed.

Plate Clamps

Devices used to lift large, heavy steel plates in hoisting operations.

Qualified Inspector

A certified professional or manufacturer representative responsible for inspecting hoists or rigging systems.

Ratchet

A circular mechanism with uniform ridges that facilitates line retrieval, often found in winches and hoists.

Reeving

The path that the wire rope follows as it unwinds from the hoist drum and wraps around the sheaves.

Rigging

All necessary equipment or hardware used to attach a load to the hoist.

Running Sheave

A sheave that rotates as the hook is raised and lowered, helping guide the lifting medium.

Side Pull

The horizontal portion of the hoist’s pull when the lifting lines are not acting vertically.

Sheave

A grooved wheel or pulley that changes the direction and application point of the pulling force.

Tag Line

A rope used to prevent load rotation by controlling the orientation of the suspended load.

Trolley

A wheeled mechanism that is supported by a frame, from which the hoist is suspended. It enables movement of the hoist to transport the load.

Winch

A lifting device featuring a horizontal cylinder that winds wire rope or chain using a crank to raise or lower loads.