Electric Transformers

Electric transformers are inductively coupled electromagnetic devices designed to transfer electrical energy between circuits. They play a critical role in the operation of all electronically powered equipment by converting electrical currents into voltages tailored to specific applications. Power transformers ensure that electrical systems receive the appropriate voltage for optimal performance, while current transformers are essential for storing and transmitting energy efficiently through power lines and grids.

Electric Transformers FAQ

What is the main purpose of an electric transformer?

Electric transformers regulate electrical voltage to ensure safe and efficient operation of electronic devices. They convert power between circuits by stepping voltage up or down as needed, preventing equipment damage and ensuring optimal performance.

How do electric transformers work?

Transformers operate using electromagnetic induction. Alternating current in the primary coil creates a magnetic field that induces voltage in the secondary coil. Depending on coil windings, this process either increases or decreases voltage for power distribution.

What is the difference between a step-up and step-down transformer?

A step-up transformer increases voltage by having more windings in the secondary coil, while a step-down transformer reduces voltage using fewer windings in the secondary coil. Both maintain energy transfer efficiency across circuits.

What are distribution transformers used for?

Distribution transformers lower high transmission voltages to safer levels for residential and commercial use. Typically rated between 3 and 500 KVA, they play a crucial role in local power delivery systems across North American grids.

Why are toroidal transformers more efficient?

Toroidal transformers, shaped like a ring, reduce electromagnetic interference and energy loss. Their continuous winding design minimizes leakage and noise, making them ideal for sensitive electrical equipment and compact installations.

What type of cooling do dry-type transformers use?

Dry-type transformers rely on natural or forced air circulation instead of oil for cooling. This design lowers environmental risk and allows safe use in indoor industrial and commercial environments.

How does transformer insulation impact performance?

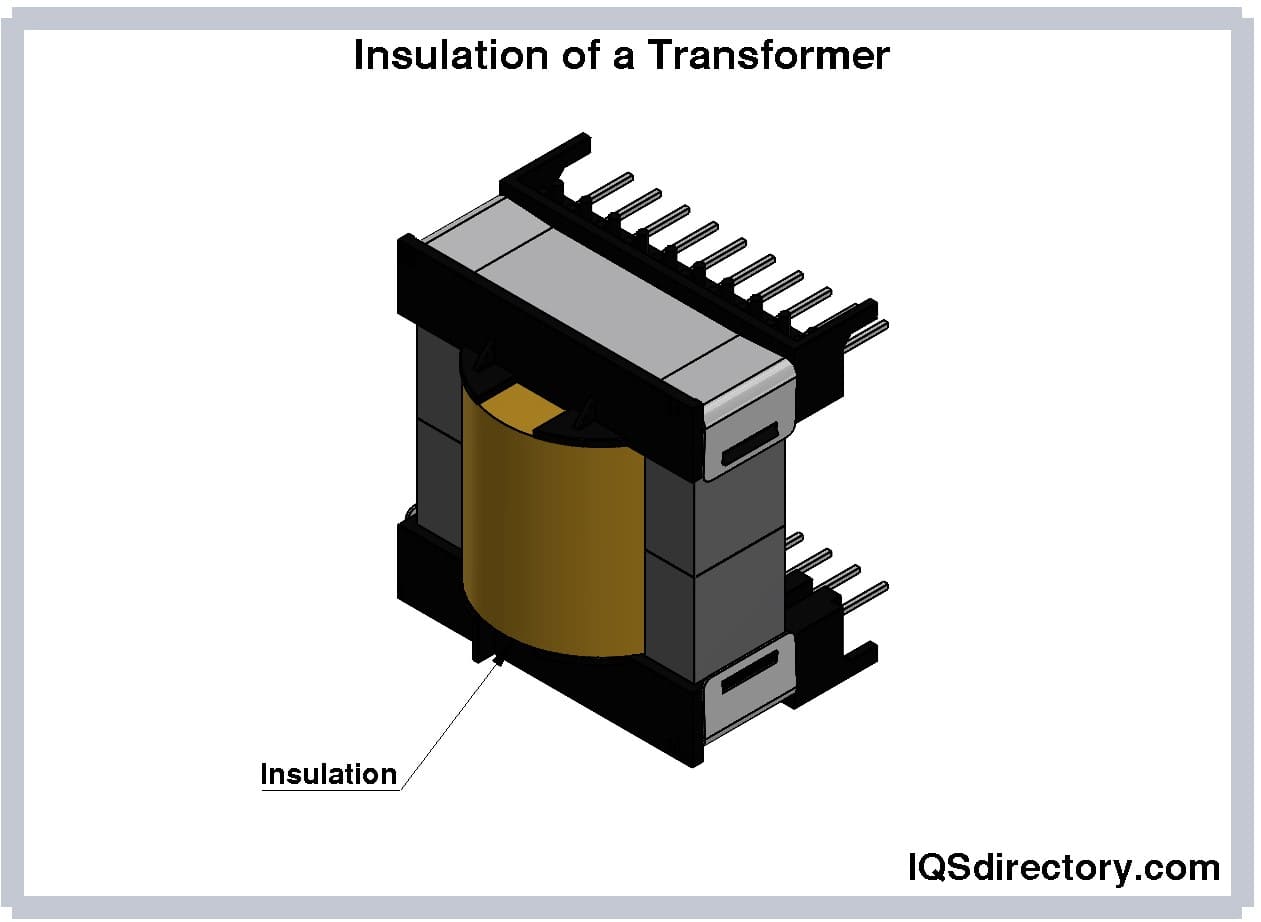

Proper insulation prevents electrical short circuits and overheating within transformers. Failure of insulation can cause severe damage or equipment loss, so high-quality materials are essential for safety and reliability in power systems.

What should be considered when selecting a transformer manufacturer?

Selecting a transformer manufacturer involves balancing cost, quality, and customization. The best manufacturers collaborate to design efficient solutions tailored to specific power requirements rather than offering standard models alone.

History of Electric Transformers

In the 1830s, Michael Faraday and Joseph Henry independently discovered the principle of electromagnetic induction through their pioneering work with electromagnets. Despite being on separate continents and having no collaboration, both men made their groundbreaking discoveries within a year of each other.

Faraday’s work led to what became known as Faraday’s Law, which would ultimately pave the way for the invention of the first transformer nearly 45 years later. Through a series of experiments, Faraday demonstrated how an electromagnetic field could induce an electrical current. In one key experiment, he wrapped two coils around opposite sides of an iron ring. One coil was connected to a galvanometer, while the other was attached to a battery. As he suspected, when the battery was connected, the coil with the galvanometer showed a current. However, the true breakthrough came when he disconnected the coil from the battery and observed that a current still flowed, proving that the battery continued to induce power in the second coil without direct physical connection. This discovery laid the foundation for the development of the transformer.

Decades later, Ottó Bláthy, Miksa Déri, and Károly Zipernowsky, working in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, built upon Faraday’s discoveries to create the first toroidal-shaped transformer. Their design was specifically developed for alternating current (AC) incandescent lighting systems, marking a major advancement in electrical engineering. While their initial invention in Budapest, Hungary, in the mid-1870s was revolutionary, it would take another decade before transformers became practical for widespread use.

By the 1880s, William Stanley and George Westinghouse introduced the first commercially viable transformers. In 1886, Stanley's transformer was successfully used to provide power to Great Barrington, Massachusetts, making history as the first commercial application of a transformer-based electrical system. This innovation laid the groundwork for the electrical infrastructure we rely on today. Modern transformers are embedded in all forms of electronic circuitry, found on utility poles supporting power lines, built into lamps, and even integrated into small devices like flashlights.

How Transformers Work

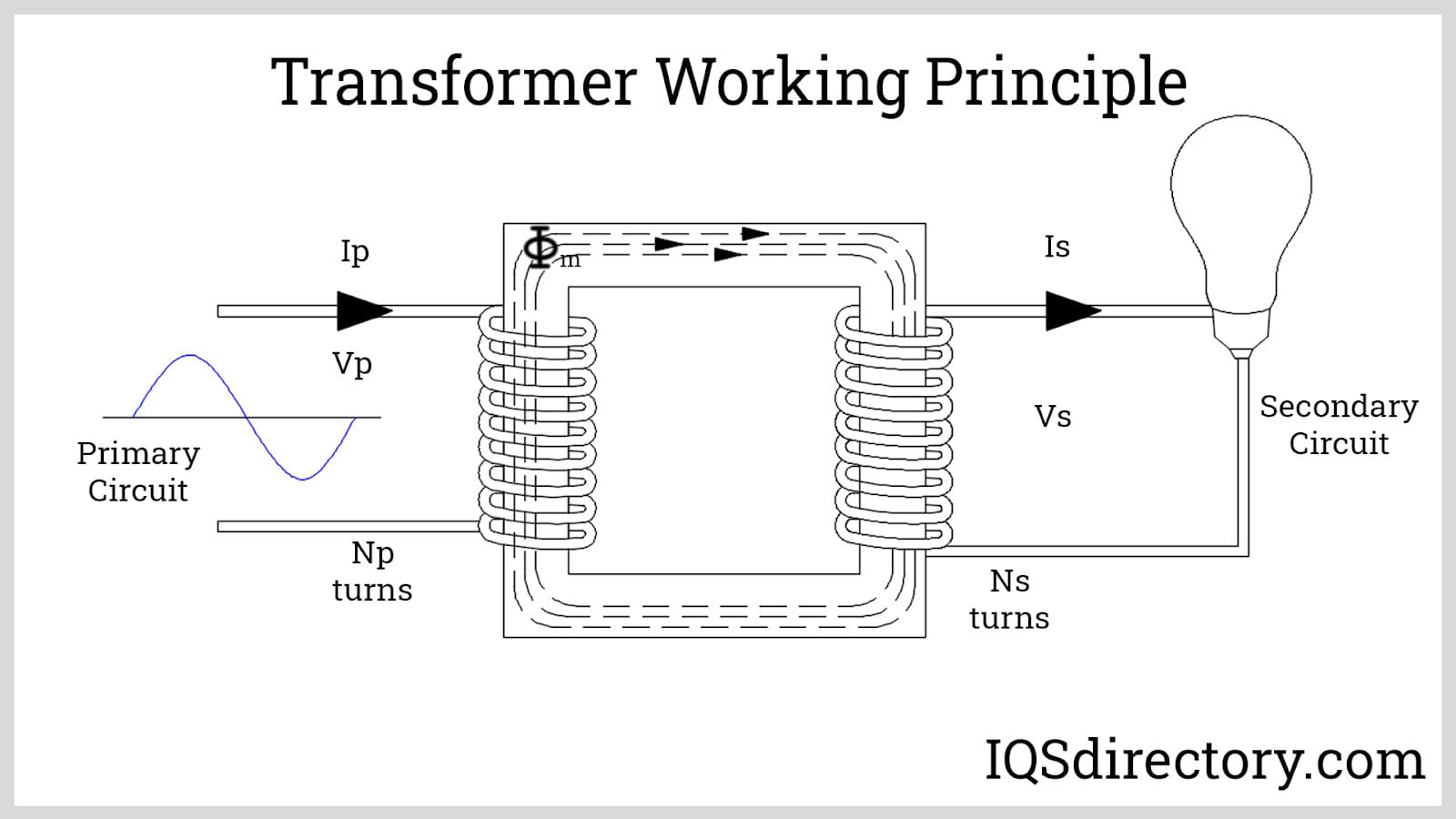

Transformers function based on the principle of electromagnetic induction, which requires an electromagnetic field to be present. To achieve this, a coil wrapped around a core is charged with an alternating current, generating a primary voltage. As energy flows through the coil, it creates an electromagnetic field—also known as a magnetomotive force—that travels through the core to a secondary coil, inducing a secondary voltage.

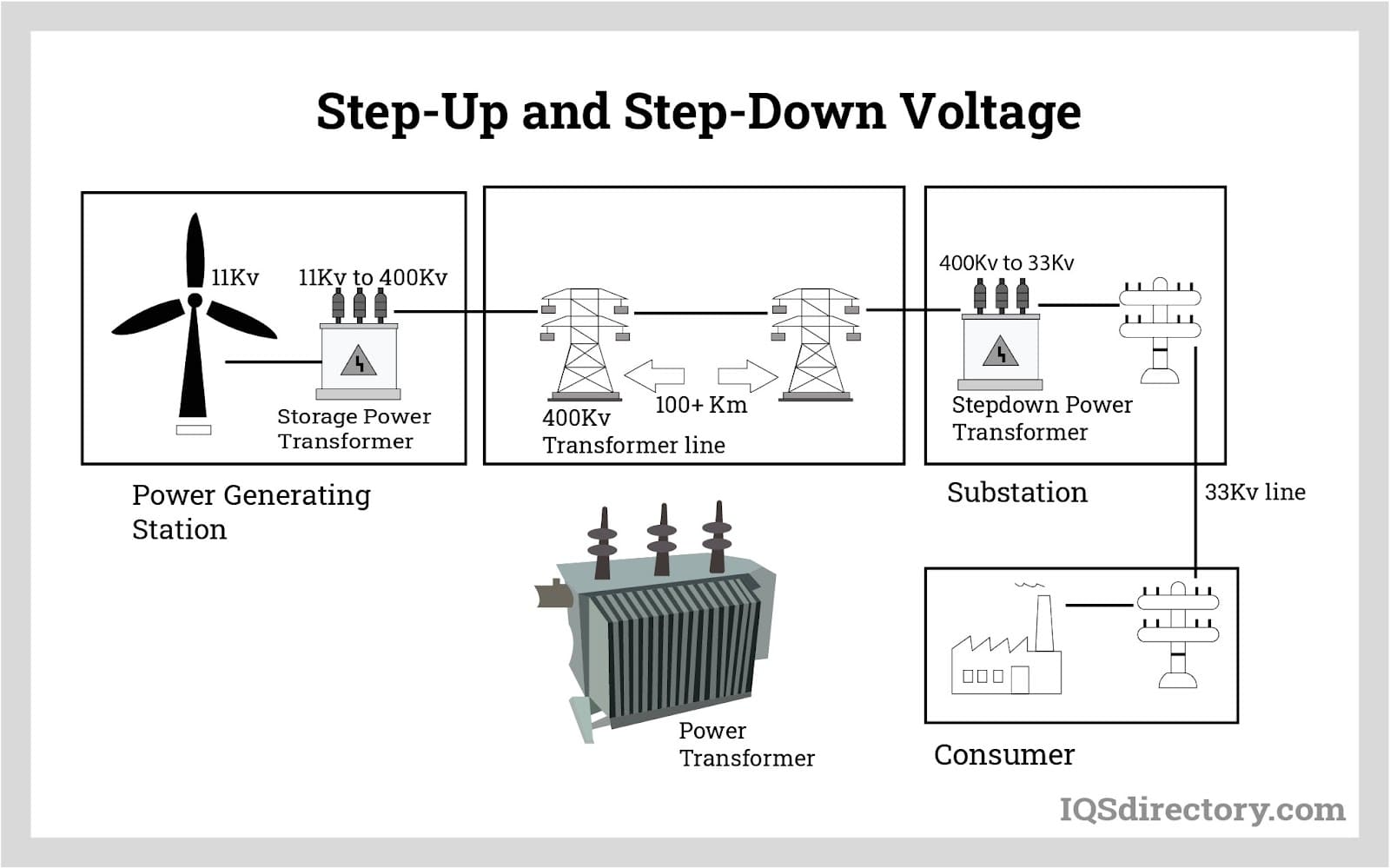

The input voltage of a transformer is determined by the power source, while the output voltage depends on the secondary coil. If the number of windings in the secondary coil matches the primary coil, the output voltage remains the same as the input. However, if the secondary coil has fewer windings than the primary, the voltage decreases, forming what is known as a step-down transformer. Conversely, when the secondary coil has more windings than the primary, the voltage increases, creating a step-up transformer.

During operation, some energy is inevitably lost in the form of heat within the magnetic field of the transformer. To mitigate this energy loss, many transformers submerge their coils in a cooling agent. Manufacturers frequently employ a concentric coil configuration, where both the primary and secondary coils are wound together around the core. This design is especially prevalent in three-phase transformers.

Once the transformer adjusts the voltage, electricity is transported through power lines and distributed across power grids. Step-up transformers elevate voltage levels for long-distance transmission, reducing energy loss, while step-down transformers decrease voltage to safe levels for consumer use. This process ensures that electrical devices receive the correct voltage. If the voltage is too low, the device may fail to operate efficiently and suffer long-term damage. If the voltage is too high, it can destroy the device, potentially leading to electrical fires or shock hazards if it exceeds the device’s peak voltage capacity.

Electric Transformer Types

3 Phase Transformers

Used to regulate voltage in three-phase electrical transmission systems, these transformers have three primary windings connected to each other and three secondary windings also interconnected. They efficiently distribute electrical power across industrial and commercial grids.

Auto Transformers

These transformers feature a single winding that serves as a common link between both circuits, eliminating isolation between them. Their design makes them one of the most cost-efficient transformer types, reducing material and manufacturing costs while still providing effective voltage conversion.

Current Transformers

Designed to measure electrical current, these transformers have a primary winding integrated into the circuit. By scaling down high current levels to a measurable range, they allow for accurate monitoring and control in power distribution systems.

Distribution Transformers

Typically rated between 3 and 500 KVA with voltage levels of 601 volts or higher, these transformers are used in electrical distribution networks to step down voltage for residential and commercial applications.

Dry Type Transformers

Instead of liquid-based cooling or insulation, these transformers rely on air circulation for temperature regulation. Their design reduces environmental risks and makes them ideal for indoor applications.

High Resistance Transformers

These transformers feature high leakage reactance, which limits output current to a specified value in the event of a fault. This safety feature helps prevent electrical overload and damage to connected equipment.

High Voltage Transformers

Built to handle electrical energy at high voltage levels, these transformers ensure efficient power transmission across long distances. Instrument transformers within this category provide precise measurement and monitoring of power voltage as it transfers proportionally between primary and secondary coils.

Inverters

Devices that convert electrical power between alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC). They play a critical role in renewable energy systems, uninterruptible power supplies, and industrial applications.

Isolation Transformers

Designed to insulate the primary circuit from the secondary circuit, these transformers allow AC power transfer between devices without direct electrical connection. By preventing ground loops and enhancing safety, they help protect sensitive electronic equipment from voltage surges and interference.

Laminated Core Transformers

Among the most widely used transformer types, these units are commonly found in household appliances, where they step down voltages for safe operation. Their laminated core minimizes eddy current losses, improving efficiency.

Low Voltage Transformers

Engineered to reduce voltage to lower, safer levels, these transformers are commonly used in applications such as LED lighting, control circuits, and low-power electronics.

Polyphase Transformers

These transformers can either be a combination of multiple single-phase transformers or a single polyphase unit. Many polyphase transformers incorporate a zigzag winding configuration, particularly in grounded electrical systems, to enhance stability and power quality.

Power Transformers

Responsible for converting electrical voltage to lower levels, these transformers facilitate efficient power distribution across industrial and commercial networks, ensuring stable operation of electrical systems.

Pulse Transformers

Designed for waveform transmission, these wide-band transformers primarily transfer rectangular electrical pulses with rapid rise and fall times while maintaining a consistent amplitude. They are commonly used in digital circuits, telecommunications, and radar applications.

Step Down Transformers

Have the power to convert higher voltages to lower voltages by means of transferring electrical energy through two coil stages, the second coil stage having fewer coil windings.

Step Up Transformers

These transformers lower high voltages to safer, usable levels by transferring electrical energy between two coil stages, with the secondary coil having fewer windings than the primary. They are essential in residential and commercial electrical distribution systems.

Toroidal Transformers

Originating from early designs by Hungarian engineers Ottó Bláthy, Miksa Déri, and Károly Zipernowsky, these donut-shaped transformers are highly space-efficient and excellent at reducing electromagnetic interference. Their winding process is slow and requires specialized equipment, making them more expensive to manufacture. Toroidal inductors also limit AC flow and suppress high-frequency noise, improving electrical performance.

Zig Zag Transformers

These special-purpose three-phase transformers provide grounding for ungrounded electrical systems while also filtering and controlling harmonic currents. Their unique configuration allows them to manage power distribution in complex electrical networks, ensuring stable operation and minimizing electrical noise.

Purpose of Transformers

Transformers serve as essential regulators of electrical voltage, ensuring that the appropriate amount of power is supplied for a specific application. If the voltage is too high, it can severely damage electronic devices, potentially causing malfunctions, electrical fires, or even dangerous arcs of electricity. Conversely, if the voltage is too low, the device may not function properly, leading to inefficiencies or failures. To prevent these risks, transformers regulate voltage before electricity reaches the intended device, safeguarding both performance and safety.

Power transformers play a critical role in virtually every electrically powered device and system. Their primary function is to adjust the current to the required voltage level, making it usable for the specific application. Whether powering a computer, hair clippers, or a remote-control car, transformers ensure that electricity is transferred efficiently and safely. The regulation of electrical flow allows devices to operate as intended without the risk of overloading or underpowering.

Beyond voltage conversion, electric transformers also serve additional functions, such as isolating different sections of a circuit from one another. This isolation enhances electrical safety and prevents interference between connected components. Use IQS Directory to locate the power transformation equipment that meets your specific requirements.

Electric Transformer Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

Electric transformers are static electrical machines that transform electric power from one circuit to the other without changing frequency.

The electric transformers usage of the properties of the electricity to change the voltage of the electricity either making it high or to a lower degree.

Insulation is the most important requirement for transformers and in case of failure, severe damages to the transformers can occur.

The transformer either step up or step down voltage levels ensuring a safe and efficient power system.

Things to Consider When Purchasing a Transformer

Transformers operate under Faraday’s Law, making them indispensable for storing and transporting electrical power. Since their commercial introduction in 1886—when they were first used to power Great Barrington, Maine—transformers have remained in continuous use in various forms. They provide the safest and most efficient means of transferring electricity between circuits, with many units capable of supplying power to entire towns and large sections of major cities.

Transformers can be tailored to meet specific requirements, and while there are many standard types available, custom solutions are often necessary for specialized applications. Finding the right transformer starts with finding the right manufacturer. A good manufacturer and the right manufacturer, however, are not necessarily the same.

There are many reputable manufacturers, but the right one depends on your particular needs. While pricing is a logical starting point, it is important to recognize that quality often correlates with cost. The best manufacturer for your project is one that works collaboratively to identify the most effective power solutions for your operation rather than simply pushing the most expensive option.

Understanding what you need from a transformer is essential, but even if you are uncertain about the best fit for your power system, experienced manufacturers can guide you toward the optimal choice. Navigating the complexities of mechanical and electrical systems can be challenging, but you do not have to do it alone. To explore a range of transformer manufacturers who can meet your needs, return to the top of this page for a comprehensive list of trusted suppliers.

Electric Transformer Terms

Air Cooled

A transformer that dissipates heat using air, either through natural ventilation or forced-air cooling with fans.

Auto Transformer

A transformer that operates with a single winding per phase, reducing size and material costs while maintaining efficient voltage transformation.

Banked

Refers to multiple single-phase transformers connected together to supply power to a three-phase load, enhancing distribution flexibility.

Core

The central magnetic structure of a transformer, responsible for intensifying the magnetic field and directing energy transfer between windings.

Core Saturation

A condition where a transformer or inductor reaches its maximum magnetic capacity, preventing further increases in magnetic flux and potentially affecting performance.

Delta

A three-phase transformer connection in which windings form a closed loop, allowing balanced power distribution and efficient load management.

Duty Cycle

The proportion of time a transformer can continuously supply its full-rated power to a load. This measurement is crucial in determining the appropriate transformer size for an application.

Electrostatic Shielding

A shielding layer placed between windings—typically between the primary and secondary—to enhance isolation. Additional shielding may be used between secondary windings, with all shields typically grounded to the core.

Encapsulated

A dry-type transformer with an enclosed core and coil assembly, providing added protection against contaminants and environmental exposure.

Exciting Current

The amount of current a transformer draws when operating at nominal input voltage without a connected load.

Ferroresonance

A resonance condition caused by core saturation in an inductive component, which increases inductive reactance relative to capacitive reactance, potentially leading to voltage instability.

Filter

A system within a transformer composed of capacitors, inductors, and resistors, designed to selectively allow certain frequencies or direct current while blocking or attenuating undesired frequencies.

Flexible Connector

A conductive component that accommodates thermal expansion and contraction while also helping to reduce noise and mechanical stress.

Impedance

The total resistance to current flow in an AC circuit, combining resistance, inductive reactance, and capacitive reactance.

Inductance

The ability of a coil to store energy in its magnetic field and resist changes in current flow. It is influenced by the core material, the number of turns in the coil, and the coil’s cross-sectional area.

Inrush Current

A brief surge of current that occurs when a transformer is first energized, often due to residual flux in the core.

Isolation Transformer

A transformer with physically separated primary and secondary windings, allowing for magnetic coupling while minimizing electrostatic coupling and improving circuit isolation.

KVA

Kilovolt-Ampere rating, which defines the power-handling capacity of a transformer without exceeding its temperature limits.

Load

The amount of electrical power supplied or required at a specific point in a system. It also refers to the power demand (KVA or VA) placed on a transformer by connected devices, such as light bulbs or appliances.

Magnetic Shielding

A conductive material surrounding a transformer’s coils that reduces stray magnetic fields and prevents interference with nearby components.

Polarity

The directional relationship between current flow in two transformer leads. Transformers have either additive or subtractive polarity, which affects phase alignment in electrical systems.

Power Factor

The ratio of real power (watts) to apparent power (volt-amps), expressed as KW/KVA. Power factor accounts for the phase difference between voltage and current caused by inductive or capacitive loads. Harmonic power factor considers distortions from nonlinear loads.

Rated Power

The combined voltage and current output capability derived from all secondary windings of a transformer.

Reactance

The opposition to changes in alternating current, divided into capacitive reactance (related to capacitors) and inductive reactance (related to inductors and coils).

Resonance

An AC circuit condition in which inductive and capacitive reactances interact, creating maximum or minimum impedance.

Secondary Winding

The transformer winding that connects to the load or output side, providing the desired voltage level.

Sudden Pressure Relay

A pressure-sensitive switch designed to disconnect a transformer from the power supply in response to internal pressure surges.

Voltage

The measurement of electrical potential difference, indicating the force exerted on a unit charge due to surrounding electrical fields.

Voltage Regulation

The percentage change in output voltage from no-load to full-load conditions, reflecting the transformer's ability to maintain consistent voltage levels.

Voltage Taps

Additional connection points on a transformer winding that allow for adjustments in voltage output. Typically found on primary windings, these taps enable transformers to operate across different national grid voltages.

More Electric Transformers Information