Forging

Forging is the process of shaping metal through compressive force, causing plastic deformation that transforms raw material into a desired form. This process is typically carried out using a hammer or die, with methods that vary depending on temperature. Forgings can be hot or cold processed, depending on the composition of the material and the specific demands of the application. The range of forged pieces spans from a few grams to several thousand pounds, crafted from various metals and alloys to suit different uses. Forged products are found in everyday and industrial settings, including kitchenware, tools, hardware, weapons, and jewelry. Larger-scale applications include engine blocks, ship valves, and mining drill bits.

The forging industry encompasses a range of specialized professions, such as boiler making, ironworking, blacksmithing, and die cutting. In addition to hands-on metalworking, related fields include casting, machining, and sheet metal fabrication. Large-scale operations require skilled heavy equipment operators and drivers to facilitate production. While historically a male-dominated trade, women are an increasing presence in the industry, now representing 5% of the workforce.

Once defined by the blacksmith’s hammer and anvil, forging has evolved with advanced machinery. Hydraulic drop hammers, forging presses, and power-driven tools now shape metal with precision and efficiency. Some presses use extreme pressure to force metal into molds or dies, while others rely on pneumatics, hydraulics, or electricity to hammer, roll, and bend metal into the required shape. Forging remains a cost-effective alternative to weld fabrication or casting, which requires molten metal and specialized molds. With minimal secondary operations, forging allows for flexible designs and produces strong, defect-free components by eliminating internal gas pockets.

Forging FAQs

What is forging in metalworking?

Forging is a process that shapes metal using compressive force from a hammer or die, creating strong, defect-free components. It alters the metal’s internal grain structure, improving durability and mechanical performance for applications ranging from tools to industrial machinery.

How does hot forging differ from cold forging?

Hot forging heats metal above its recrystallization point, making it easier to shape with less force. Cold forging occurs at or near room temperature, preserving the metal’s structure and producing tighter tolerances and increased strength without scaling or oxidation.

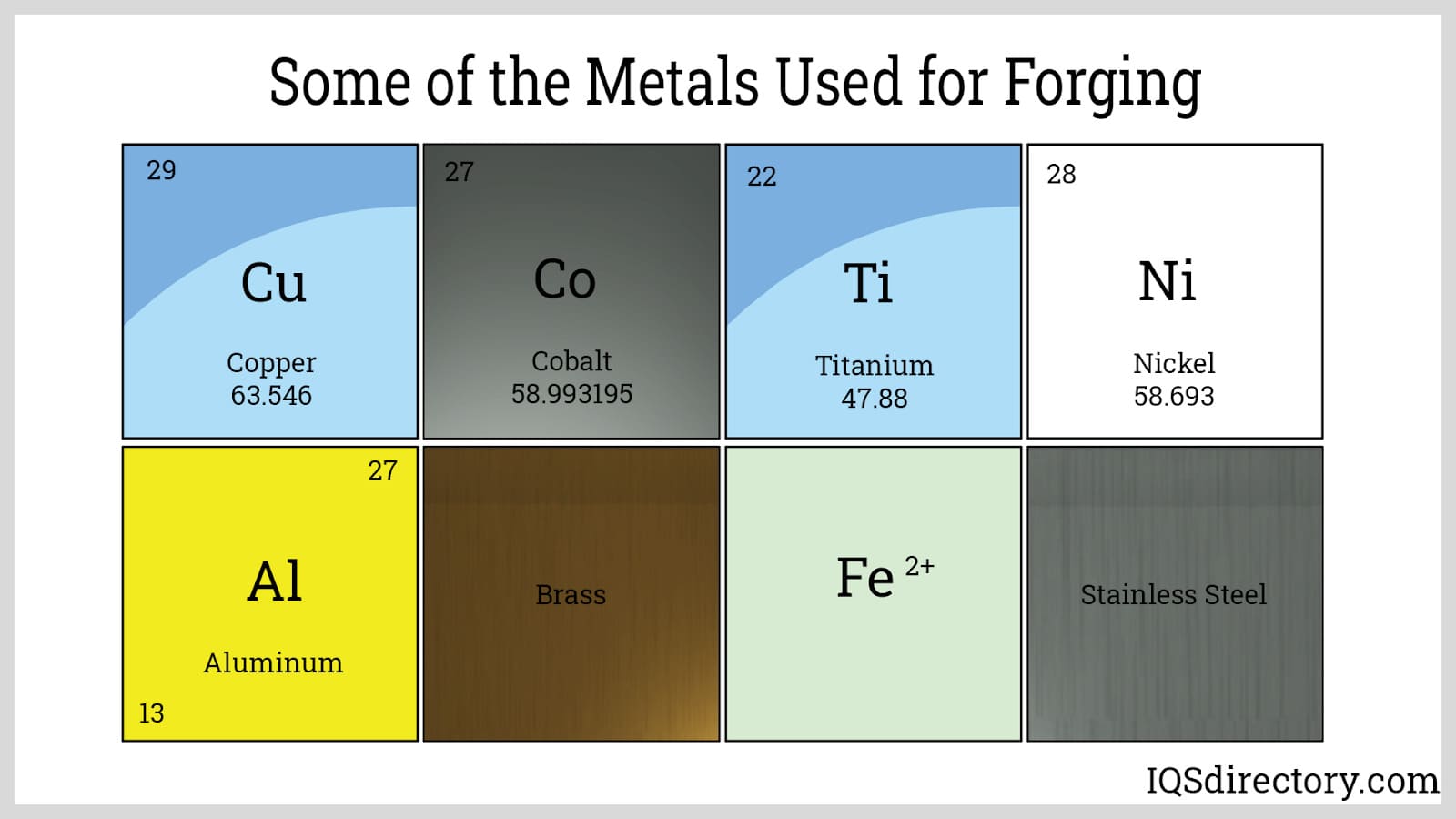

What materials are commonly used in forging?

Common forging materials include iron, carbon and stainless steels, aluminum, titanium, copper, and nickel alloys. Each metal offers unique properties—such as aluminum’s lightness, titanium’s strength, or copper’s conductivity—tailored to specific industrial or structural applications.

What are the main types of forging processes?

Key forging processes include open die forging, closed die forging, roll forging, and automatic hot forging. These methods vary in temperature, precision, and production volume, with open die best for custom shapes and closed die ideal for complex, repeatable parts.

Why is forging preferred over casting or machining?

Forging produces stronger, more reliable components by eliminating internal gas pockets and improving grain structure. It requires fewer secondary operations than casting and provides better dimensional accuracy and fatigue resistance than machining or weld fabrication.

What industries rely on forged components?

Forged parts are critical in aerospace, automotive, defense, mining, and energy sectors. They’re used for gears, valves, engine blocks, and ship components—applications demanding high strength, durability, and precision under extreme operating conditions.

How has forging evolved over time?

Forging began with ancient blacksmiths and evolved through innovations like the water wheel, steam power, and the Bessemer Process. Modern techniques use hydraulic presses and computer-controlled equipment to produce complex metal parts with exceptional accuracy and consistency.

A Brief History of Forging

As early as 4500 B.C., Sumerians in the Tigris and Euphrates River Valleys were forging softer metals, heating copper and bronze over fires and shaping them with rocks into primitive tools. By 750 B.C., during the Iron Age, the invention of the Bloomery Furnace—a structure of stone and clay that utilized bellows to intensify heat—enabled the widespread use of iron. The ancient Romans held forging in such high regard that they prayed over their forges to the god Vulcan. Between the 10th and 12th centuries A.D., innovations such as the water wheel, followed by the development of hammers and forced-air bellows, dramatically increased productivity. Evidence suggests that metal horseshoes were being forged as early as 900 A.D., though the most commonly produced items were knives and tools, with rudimentary jewelry beginning to emerge on the eve of the Dark Ages.

The forging industry saw significant expansion during the Dark Ages, when warfare dominated Europe. The demand for weapons surged, leading to large-scale production of knives, swords, and spearheads. Despite its growth, the industry remained relatively unchanged until the Industrial Revolution. The 19th century saw the introduction of the steam engine, which provided power to forges in nearly any location, fueling advancements across the globe.

A major breakthrough came in 1856 with the discovery of the Bessemer Process, which enabled the mass production of steel from pig iron through high-temperature oxidation using blasts of air. With an abundance of raw materials, the Colt Arms Company pioneered the closed-die process, allowing for the mass production of gun components through forging and machining. The modern forging press emerged in the 1930s, revolutionizing metal shaping by applying continuous pressure rather than repetitive hammer blows to form metal with greater precision.

Products of Forging and Their Applications

Forging transforms metal by redirecting its internal grain structure, resulting in components of exceptional strength and durability. This process allows for endless reproduction of identical parts or provides the flexibility to sculpt intricate metal forms. With forges and forge presses designed to meet any specification, metalworking has continued to evolve, incorporating new techniques that enhance structural integrity and expand the range of applications.

Forged parts play a crucial role in industries such as aerospace, aviation, defense, oil and gas, mining, shipping, transportation, and food processing. These components range from the smallest bolts to massive ship anchors, train tracks, augers, and gears, each benefiting from the strength and reliability that forging provides. Whether shaping industrial equipment or creating specialized fasteners, forged products remain a cornerstone of modern manufacturing. You can find forged bolts and other components here on IQS Directory.

Materials Used in the Forging Process

Forging incorporates a diverse range of metals, including iron, aluminum, titanium, copper, nickel, and various alloys such as brass, aluminum alloy, and stainless or carbon steel. Custom alloys are also developed for specialized applications. Each metal possesses unique properties, necessitating specific treatment methods. Heat forging raises the temperature of the metal beyond its recrystallization point but stops short of melting, allowing it to be shaped through hammering or drop forging.

Iron has been a primary forging material for centuries due to its abundance and durability. Today, it is often alloyed with other elements to enhance its strength and temper. Aluminum, with its low melting point, lightweight nature, and high tensile strength, has been instrumental in the development of the aviation and aerospace industries. Copper is a soft, non-magnetic, non-sparking metal with excellent electrical conductivity, making it indispensable in electrical applications. Nickel resists oxidation and remains stable at elevated temperatures, ensuring longevity in extreme environments. Carbon Steel is an economical option with strong mechanical properties and can be heat treated (annealed) for additional strength. Stainless steel offers corrosion resistance, while titanium, though costly, provides an exceptional combination of strength and lightness, making it ideal for demanding applications.

Forging Processes

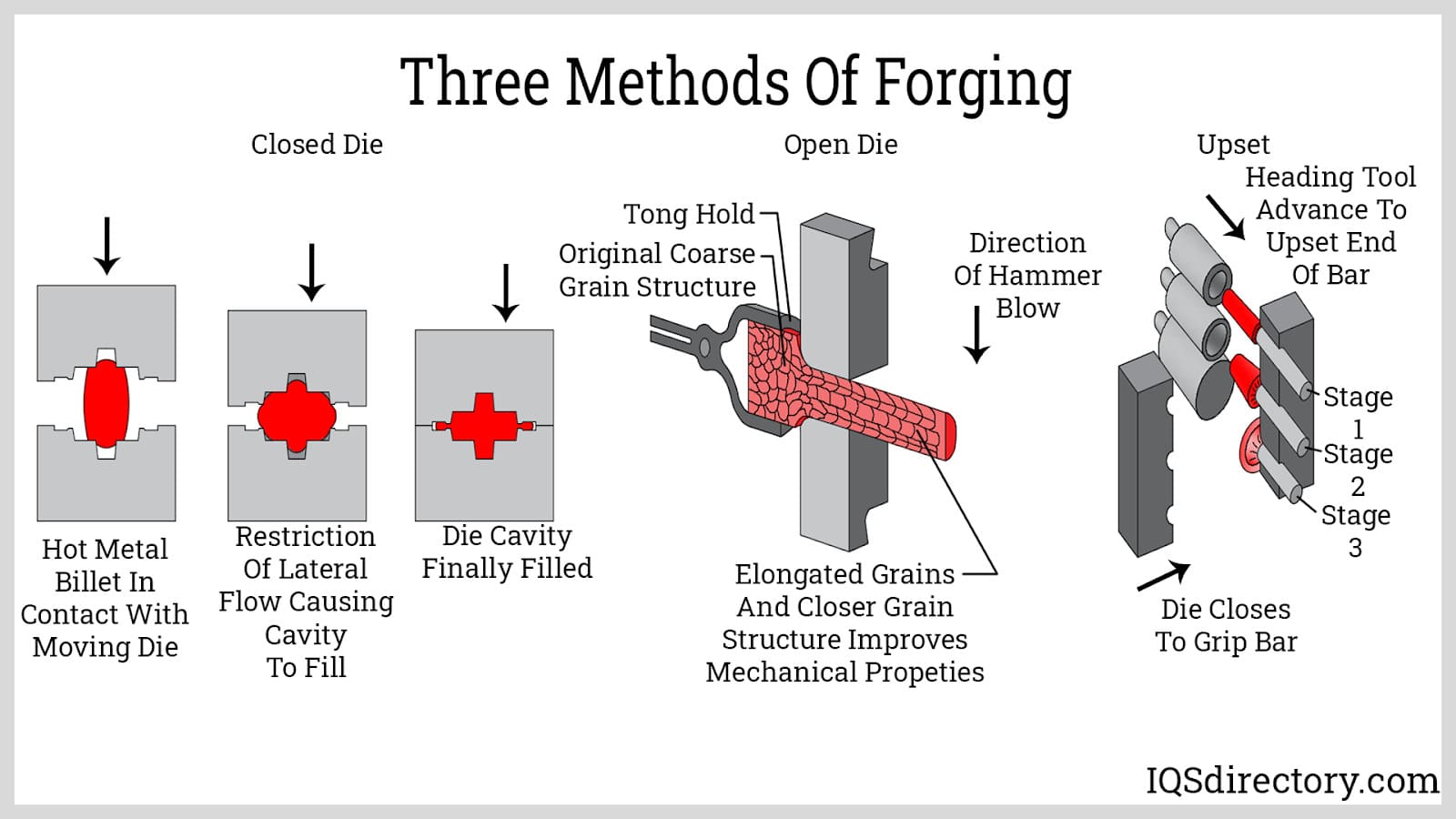

The forging process fundamentally alters the internal grain structure of metal, aligning it for increased strength, durability, and ductility. In its natural state, a base metal’s crystalline structure is randomly oriented. Forging manipulates this grain flow, creating a more organized, multidirectional arrangement, reinforcing the metal's integrity across multiple planes. Depending on the direction of the grain alignment, the material is said to be "drawn out" or "upset."

Several forging techniques are employed to achieve desired shapes and mechanical properties. Open die forging, closed die forging, roll forging, swaging, cogging, upsetting, and automatic hot forging each serve specific industrial applications. These processes operate at varying temperatures, categorized by their relationship to the material’s recrystallization point. Hot forging occurs when the metal is heated above this point, making it more malleable and easier to shape. If the temperature falls below the recrystallization point but remains above 30% of that threshold, the process is classified as warm forging. Cold forging takes place at or near room temperature, preserving the metal's original structure while increasing its strength.

Open Die Forging (Smith Forging) involves placing a workpiece on a stationary anvil and shaping it through hammer blows. The dies do not fully enclose the workpiece, allowing metal to flow except where it contacts the die. This technique optimizes grain flow, reduces void formation, enhances fatigue resistance, and improves the metal’s microstructure. Specialized techniques such as cogging, edging, and fullering refine the metal’s thickness, width, and concavity. Open die forging is particularly suited for short production runs, custom work, and artistic metalworking.

Closed Die Forging (Impression-Die Forging) involves placing heated metal within a mold or die attached to an anvil. A shaped hammer strikes the workpiece, forcing it into the cavity’s contours. Excess metal, known as "flash," is squeezed out at the die’s edges, cooling faster than the inner portion and forming a temporary seal that enhances cavity filling. Once forging is complete, the flash is removed, leaving behind a precisely shaped component. This process is widely used for producing intricate, high-strength parts.

Automatic Hot Forging is a high-speed, fully automated process that begins with metal bars rapidly heated via induction coils. These bars are descaled, cut into blanks, and then processed through a series of operations, including upsetting, preforming, final forging, and piercing. This method is ideal for mass-producing small components such as nuts and washers.

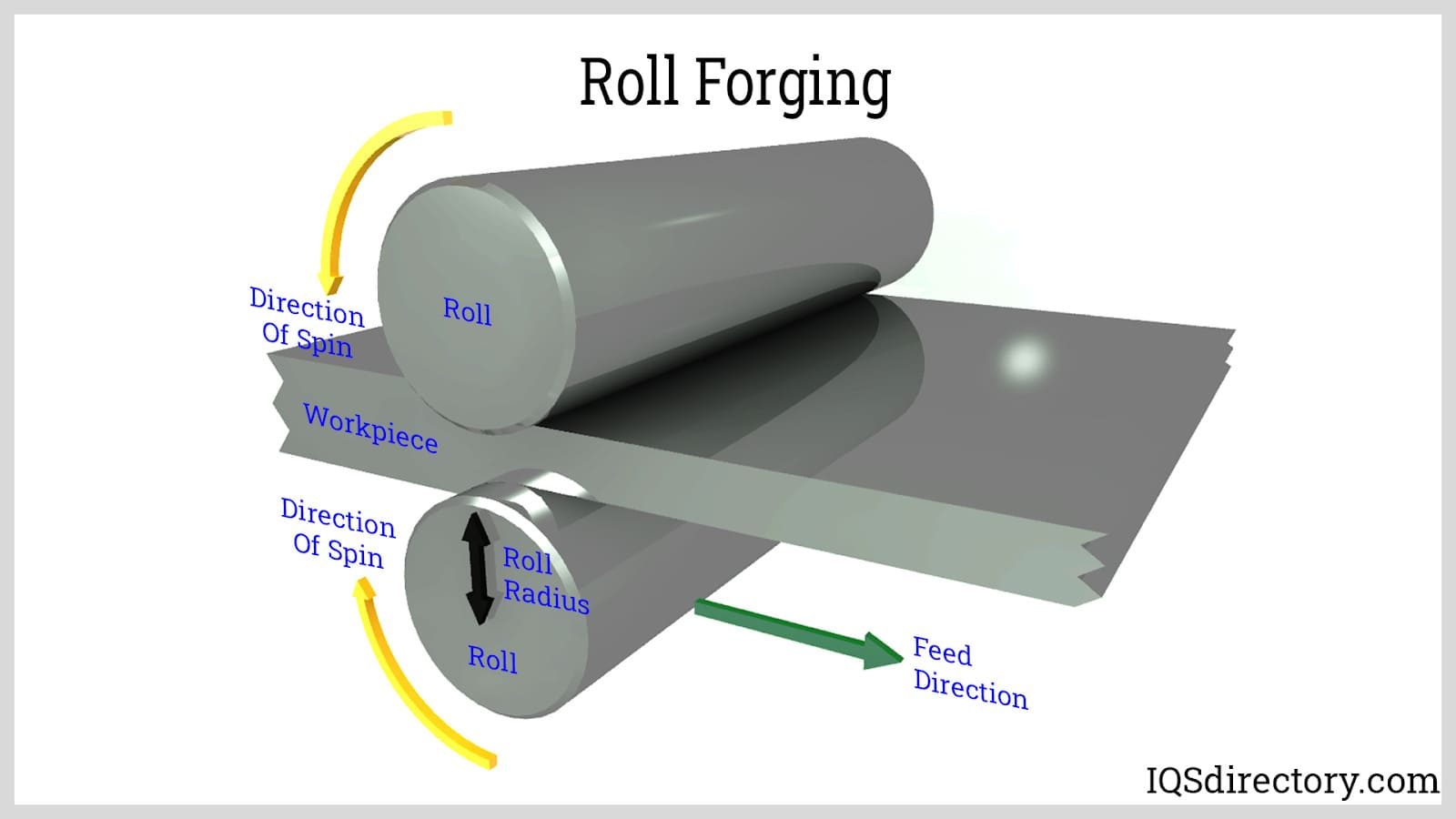

Roll Forging involves passing a heated metal bar repeatedly between two grooved rollers until the material reaches the required dimensions. Unlike closed-die forging, roll forging generates no flash, reducing material waste by 20-30%. The process enhances grain structure and is commonly used for producing axles, leaf springs, and similar components requiring uniform strength.

Each forging process offers distinct advantages. Hot forging takes advantage of increased metal malleability at high temperatures, reducing the force needed for deformation while maintaining consistent tensile strength throughout the workpiece. Aluminum hot forging occurs at relatively low temperatures, and 80% of aluminum forgings incorporate elements like silicon, magnesium, zinc, copper, or manganese to enhance strength and stability.

Warm forging reduces material scaling while maintaining a balance between formability and precision. Although it requires greater forming forces than hot forging, it achieves narrower tolerances than its high-temperature counterpart.

Cold forging allows for precise shaping at room temperature, facilitating easy material handling. It delivers the narrowest tolerances, prevents surface scaling, and significantly strengthens the final product. This method is commonly applied to softer metals such as copper, brass, bronze, gold, silver, and platinum. You can find companies specializing in cold forging here on IQS Directory.

Forging Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

Different types of metal that can be forged.

Different types of metal that can be forged.

Roll forging is a heated metal process that uses opposing rolls to shape the material.

Roll forging is a heated metal process that uses opposing rolls to shape the material.

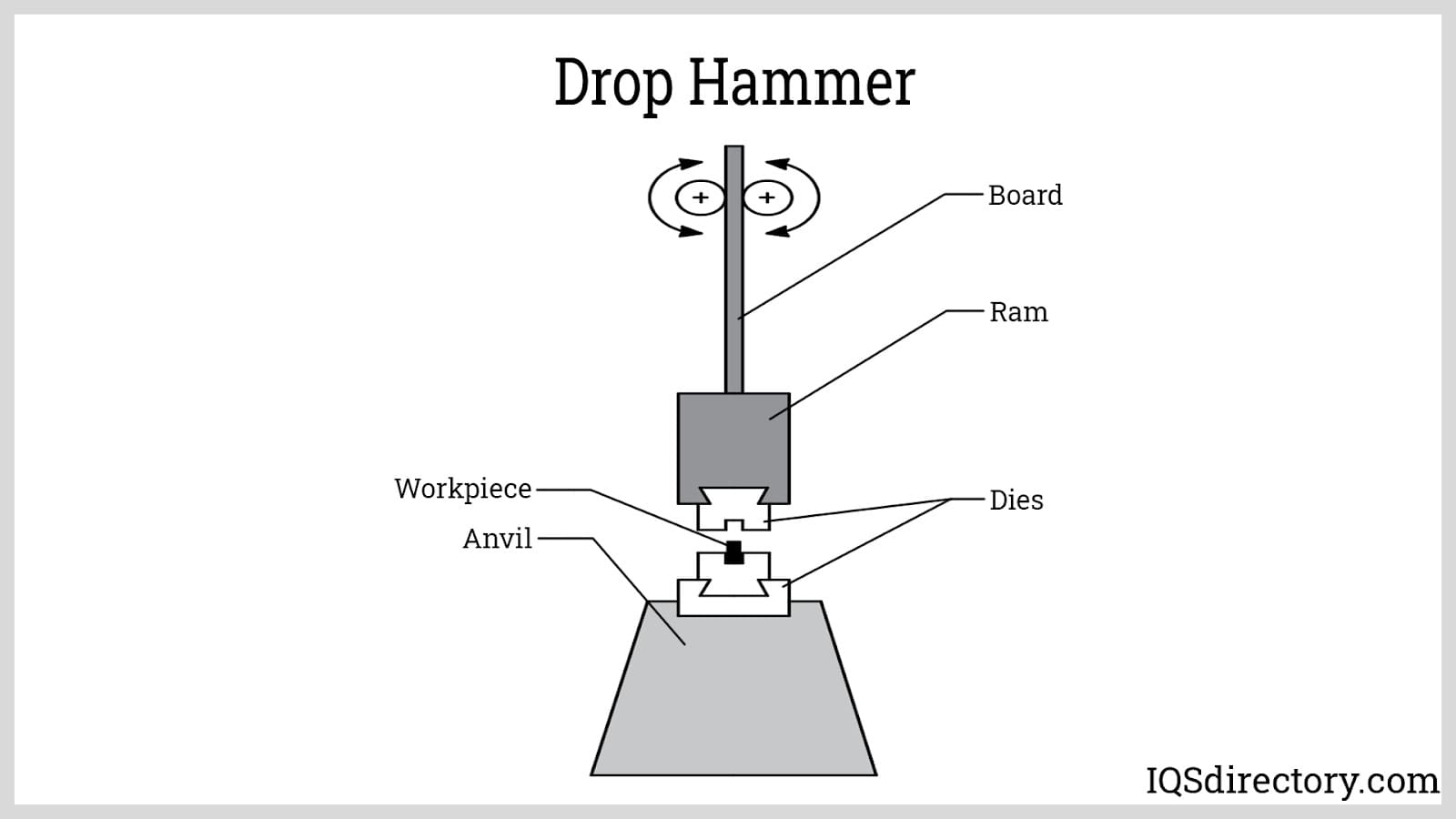

Power drop hammers use pressurized air to raise the ram to accelerate the dropping speed of the hammer.

Power drop hammers use pressurized air to raise the ram to accelerate the dropping speed of the hammer.

The three different methods of forging.

The three different methods of forging.

Forging Equipment

Different metals and applications demand specialized equipment to achieve the desired results. In both hot and warm forging, the metal must be preheated before any forging work begins. This can be accomplished through the use of a torch, oven, or electrical induction. Ovens, which may be heated with coal or gas, provide different advantages. Coal burns hotter but requires constant attention, while gas is cleaner, more user-friendly, and offers consistent heating, though at a higher cost. In cold forging, where extreme heat is not necessary, even a short period of exposure to sunlight may provide enough warmth to slightly ease the forming process.

A drop forge consists of a vertical hammer suspended over a stationary anvil. When the hammer is released, it falls with force onto the workpiece resting on the anvil, reshaping it while the excess energy dissipates through the foundation. Similar forging techniques include counterblow machines and impactors, which use hydraulic, pneumatic, or electric power to strike metal horizontally, with the opposing force being absorbed as recoil. A forging press, in contrast, applies continuous hydraulic or mechanical force, gradually pressing the raw material into the shape of the die rather than delivering a single powerful blow. For specialized applications, a ring press forge utilizes heat and concentric forces to form stock into seamless rolled rings, while a roll press forge repeatedly passes metal stock between cylindrical rollers to achieve dimensional accuracy.

The tools used in forging must be capable of withstanding immense force, high temperatures, and corrosive conditions. Dies, which shape metal within forging presses, are manufactured from high-alloy steel or tool steel to endure these extreme conditions. They can be produced through mechanical milling or casting, with the method selected depending on the application. In open die forging, the plates only make surface contact with the metal to imprint an image. In closed-die forging, the die plates must align precisely, incorporating a calculated percentage of flash to meet strict dimensional tolerances. When casting molds, a prototype is embedded in sand or coated in plaster to create a reverse image. Once the mold is set, the prototype is removed, and molten metal is poured into the cavity to produce a metal replica. This initial cast is then used to create a final mold from alloy steel, ensuring it can withstand the high pressures and repeated use of the forging process while accurately reproducing the prototype's shape.

Whether working as an artist or a large-scale manufacturer, selecting the right forging company is essential for success. A jeweler shaping delicate gold does not require the power of a 20-ton press, just as a high-volume nut and bolt manufacturer cannot rely on hand-hammered methods. The type of metal being forged—whether precious metals, iron, or stainless steel—determines the most effective forging process. Many forge companies also provide additional services, including heat treating, stress relieving, and stock hardening, as well as precision machining for dies. Some offer specialized testing and analysis, such as radiography, ultrasonic testing, or dye penetrant testing, to ensure quality and integrity. While many exceptional forge companies exist, the right one will elevate any metalworking project, whether it involves a blacksmith heating and hammering wrought iron tools by hand or a machinist crafting precision dies with computer-controlled accuracy.

Forging Terms

- As Forged

- The initial condition of a forging as it emerges from the finisher cavity, before any additional processing or finishing operations are applied.

- Backward Extrusion

- A forming process in which metal flows in the opposite direction of the applied force from the die and punch, shaping the material through controlled displacement.

- Bar

- A metal piece that has been hot-rolled from a billet into a uniform shape, which may be round, hexagonal, square, or rectangular.

- Bend

- A lengthwise deformation that occurs during the forging process or in secondary operations, such as trimming, altering the original alignment of the metal.

- Billet

- A semi-finished metal product, typically hot-rolled, with a uniform cross-section. Billets are generally larger than bars and serve as raw material for further processing.

- Block

- A forging stage where metal is progressively shaped into the desired contour through an impression die, forming a rough approximation of the final product.

- Bloom

- A semi-finished metal product with a square or round cross-section, sometimes used interchangeably with "billet," though generally larger in size.

- Board Hammer

- A type of gravity drop hammer that utilizes vertically raised wood boards attached to the ram. The boards are lifted by contra-rotating rolls and then released, allowing the ram and upper die to fall freely under gravitational force, delivering impact energy to the workpiece.

- Cavity

- A recessed area within a die that shapes the forging by confining the metal into a specific form. Typically created through machining, cavities ensure precision in die-forging applications.

- Coining

- A precision sizing process in which pressure is applied to forged parts to refine surface finishes, correct deformations, and ensure tight dimensional tolerances.

- Cold Working

- The process of altering an alloy’s size, shape, and strength through plastic deformation at temperatures below its recrystallization point. This method enhances mechanical properties without significantly affecting the material's internal grain structure.

- Die

- A tool component within a press that punches, cuts, or forms sheet metal, shaping the workpiece by applying force through a defined impression.

- Discontinuities

- Irregularities in a forging, either internal or external. External discontinuities include cracks, folds, and laps, while internal defects can manifest as porosity or segregated deformations within the material.

- Drifting

- A forging process in which a hole is created or an existing hole is enlarged through controlled punching techniques, often used in precision applications.

- Efficiency

- A measurement of how effectively applied energy is used in deforming the workpiece, expressed as a percentage of the total energy expended by the forging equipment.

- Extrusion

- A forming process in which metal is forced through a die opening in the same direction as the applied energy, creating elongated parts with uniform cross-sections. This technique is widely used in die-forging applications.

- Flash

- Excess metal that extends beyond the parting line of a die set, preventing uncontrolled material flow and ensuring complete filling of the die impression. The flash is typically trimmed away in secondary operations.

- Flow Stress

- A measure of a material’s resistance to deformation, influenced by temperature, strain rate, and composition. Flow stress is a key factor in determining the forging force required for a specific metal.

- Forging rings

- Modern forged rings serve critical roles in machine tools, aerospace applications, turbines, and high-pressure systems such as pipelines. These rings are typically forged from stainless steel, tool steel, aluminum, copper, or steel alloys to provide superior strength and durability.

- Large forging

- Forging technology has advanced over centuries, enabling the production of exceptionally large forgings. These massive components play an essential role in modern infrastructure, supporting industries such as power generation, transportation, and heavy machinery manufacturing.

- Ram

- The moving component of a press to which the punch is attached. The ram delivers force to the workpiece by driving the punch through the die to shape or cut the material.

- Ring forging

- A specialized forging process in which metal is manipulated into a hollow, circular, or cylindrical ring shape through the application of localized, compressive force. This method produces strong, seamless rings for demanding industrial applications.

- Trimming

- A secondary forging operation in which excess metal (flash) is removed from a forged workpiece to achieve the final dimensions and shape. This process ensures precision and consistency in the finished product.

- Twist

- A forging deformation that occurs across the width of a workpiece, leading to unwanted rotational displacement. Controlling twist is crucial for maintaining accuracy in high-precision components.