Hydraulic Presses

A hydraulic press is a compression molding press machine that harnesses hydraulic pressure, or fluid pressure, through a cylinder to exert force on an object. These machines are called presses because they apply downward pressure onto a substrate and die, effectively stamping the material into shape.

Hydraulic presses operate based on Pascal’s principle, which states that pressure within a closed system is distributed evenly, exerting equal force across all areas. As the most common and efficient type of industrial press, they generate a powerful lifting or compressing force that surpasses the capabilities of pneumatic and mechanical presses.

Hydraulic Presses FAQs

What is a hydraulic press and how does it work?

A hydraulic press uses hydraulic fluid to generate immense force through a system of cylinders. Based on Pascal’s principle, pressure is applied evenly across the system, compressing materials between a die and substrate to form precise shapes efficiently.

What are common applications of hydraulic presses in manufacturing?

Hydraulic presses are widely used for stamping, forging, punching, deep drawing, molding, and blanking. Industries like automotive, aerospace, packaging, and appliance manufacturing rely on them for shaping metals and producing precision components.

Why are hydraulic presses preferred over mechanical or pneumatic presses?

Hydraulic presses provide consistent force throughout the stroke, require less maintenance, and offer superior control and overload protection. They operate quietly and handle higher pressure loads than mechanical or pneumatic presses, extending tool life and ensuring accuracy.

What types of hydraulic presses are available for industrial use?

Industrial options include C-frame, H-frame, forging, platen, extrusion, vacuum, and stamping presses. Each type supports specific forming, bending, or molding operations, allowing manufacturers to match the press design to their application needs.

How do manufacturers customize hydraulic presses for different applications?

Presses can be tailored by adjusting tonnage limits, die dimensions, stroke length, hydraulic fluid type, and station configuration. This flexibility ensures compatibility with small-scale lab work or heavy-duty production exceeding 3,000 tons.

What maintenance practices keep hydraulic presses operating efficiently?

Regularly check for leaks, maintain proper oil levels, inspect seals, hoses, and fittings, and monitor operating temperature around 120°F. Keeping components lubricated and replacing electronic parts on schedule helps prevent downtime and extend machine life.

What safety features make hydraulic presses reliable for operators?

Hydraulic presses include built-in overload protection via relief valves that automatically release pressure when limits are reached. This prevents overloading, die damage, and equipment failure, ensuring safer operation across industrial environments.

Applications of Hydraulic Presses

Hydraulic presses are engineered to enable manufacturers to stamp metal materials into various finished parts. Beyond stamping, they facilitate a range of other metal forming processes, including clinching, forging, punching, shearing, molding, deep drawing, and blanking. These processes allow industries to achieve high-precision shaping and manufacturing efficiency.

Industries that depend heavily on hydraulic press services include automotive manufacturing, packaging, appliances—such as components for microwaves, dishwashers, and refrigerators—ceramics, aerospace engineering, military and defense, food and beverage processing, pulp and paper, and marine applications. Among the most widespread hydraulic press applications are beverage can fabrication and the production of automotive parts, where precision, force, and efficiency are critical.

The History of the Hydraulic Press

The hydraulic press was first invented in England in 1795 by Joseph Bramah, who was inspired to explore the properties of fluids following his development of the flush toilet. As a result, hydraulic presses are sometimes referred to as Bramah presses. His invention was based on the Pascal principle, or Pascal’s law, which asserts that pressure within a closed system remains constant and is transmitted equally in all directions.

At the time of its invention, the hydraulic press had few comparable technologies, making Bramah a pioneer in hydraulic engineering. His foundational work set the stage for the development of numerous variations on the original hydraulic press, leading to the vast range of models and applications in use today.

Benefits of a Hydraulic Press

The force generated by hydraulic presses is unmatched, far exceeding what can be achieved with mechanical or pneumatic presses. However, the benefits of hydraulic presses extend well beyond their raw power.

- Low Upfront Investment and Operating Cost

- Hydraulic presses are cost-effective due to their simple construction and minimal number of moving parts. This makes them inexpensive to purchase, easy to maintain, and straightforward to troubleshoot when compared to alternative press technologies. If a component fails, replacement is quick and does not require complete disassembly of the machine. Additionally, hydraulic equipment and supplies are readily available worldwide, ensuring minimal downtime and low maintenance costs.

- Operation of Power Stroke

- Unlike other types of presses that only deliver full power at the bottom of the stroke, hydraulic presses exert full power at any point in the stroke. This eliminates the need to invest in a heavier press—such as a 200-ton press—simply to achieve a lower force, like 100 tons, consistently throughout the stroke. This capability is particularly beneficial for drawing operations where precision and controlled force application are essential.

- Easy Operation and Built-in Protection

- A hydraulic press designed to exert a specific pressure, such as 100 tons, will apply that exact force regardless of setup errors, making it highly reliable and foolproof. Operators do not need to worry about overloading, breaking a die, or damaging the press. When a hydraulic press reaches its set pressure, the relief valve automatically opens to prevent excessive force, eliminating the risk of overload.

- Control and Flexibility

- Hydraulic presses offer a high degree of control, allowing operators to adjust various parameters according to specific application requirements. These include pressure dwell duration, direction of movement, ram force, speed, and force release. This level of flexibility ensures optimal performance for diverse manufacturing needs.

- Lower Operation Noise

- Because hydraulic presses lack flywheels and have fewer moving parts, they operate with significantly less noise than mechanical presses. Modern hydraulic presses, when equipped with a properly mounted pumping unit, comply with and often exceed current federal noise regulations, contributing to a quieter and safer work environment.

- Long Machine Tool Life

- The built-in overload protection of hydraulic presses extends the lifespan of tools. Since the pressure applied remains consistent, the risk of tool damage due to overloading is eliminated. Additionally, the absence of shock, vibration, and impact reduces wear and tear on auxiliary equipment, such as press brakes and machine guards, leading to longer service life and reduced operational costs.

How Hydraulic Presses Works

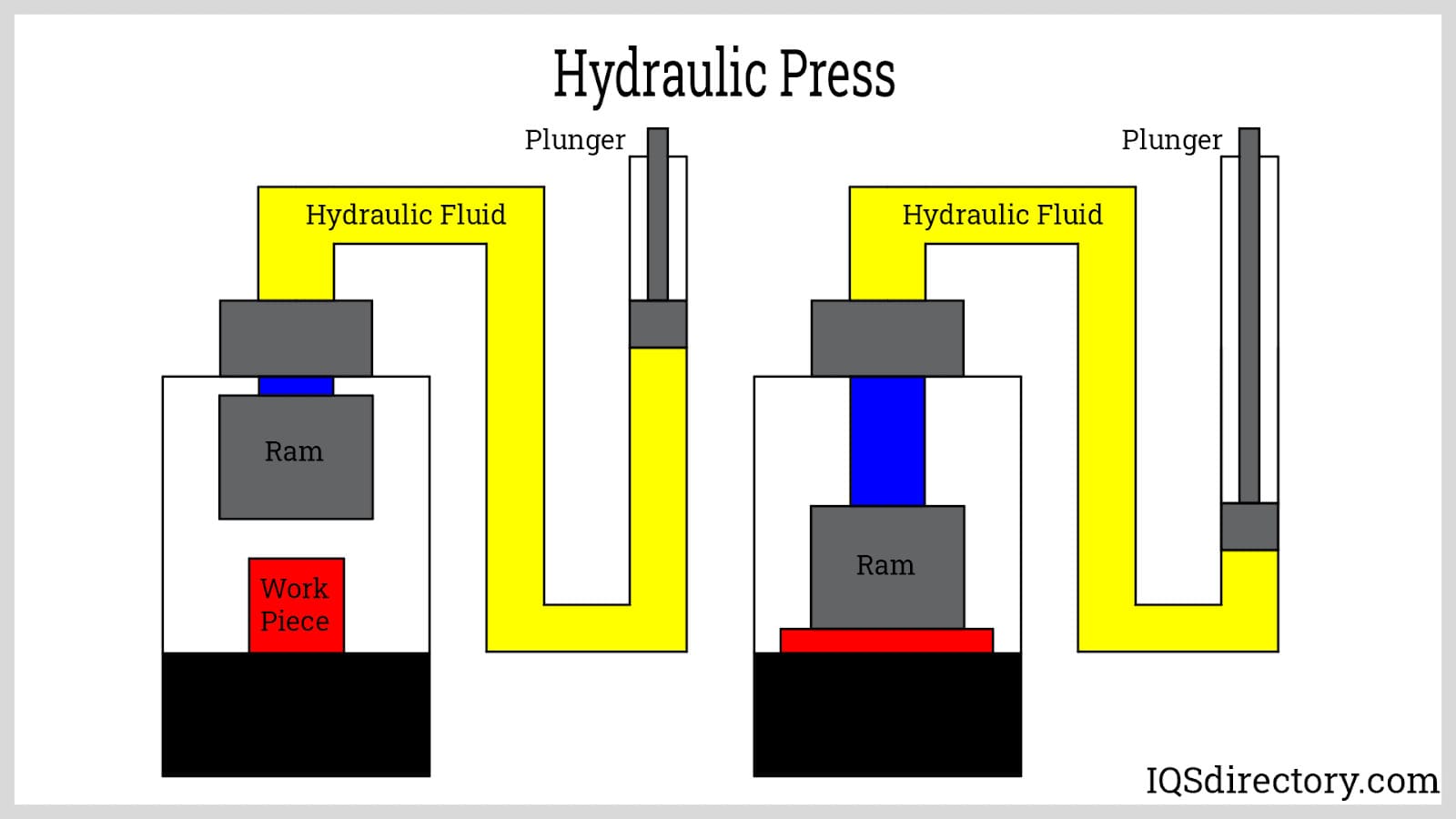

A hydraulic press operates by utilizing hydraulic fluid to generate immense force through a system of interconnected cylinders. The process begins when hydraulic fluid is forced into a small double-acting cylinder, known as the slave cylinder, by either a hydraulic pump or a manual lever. Within this cylinder, a sliding piston applies compressive force to the fluid, propelling it through a pipe into a larger cylinder, called the master cylinder. Here, the fluid undergoes additional compression under the influence of a larger piston, which, in turn, forces the fluid back into the smaller cylinder.

As the fluid cycles between the two cylinders, the pressure continues to build, increasing with each transfer. Eventually, the accumulated force becomes powerful enough to press against the anvil, baseplate, or die, initiating the material-forming process. At this stage, the press exerts force on the material, deforming it into the intended shape with precision and uniformity.

To prevent overload, the hydraulic system is equipped with a built-in pressure regulation mechanism. Once the preset pressure threshold is reached, the fluid activates a valve that triggers pressure reversal, ensuring safe and controlled operation. Because of this intelligent pressure management, hydraulic presses do not require an elaborate guiding system; the die itself naturally guides the pressing process, maintaining accuracy and efficiency throughout.

Hydraulic Press Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

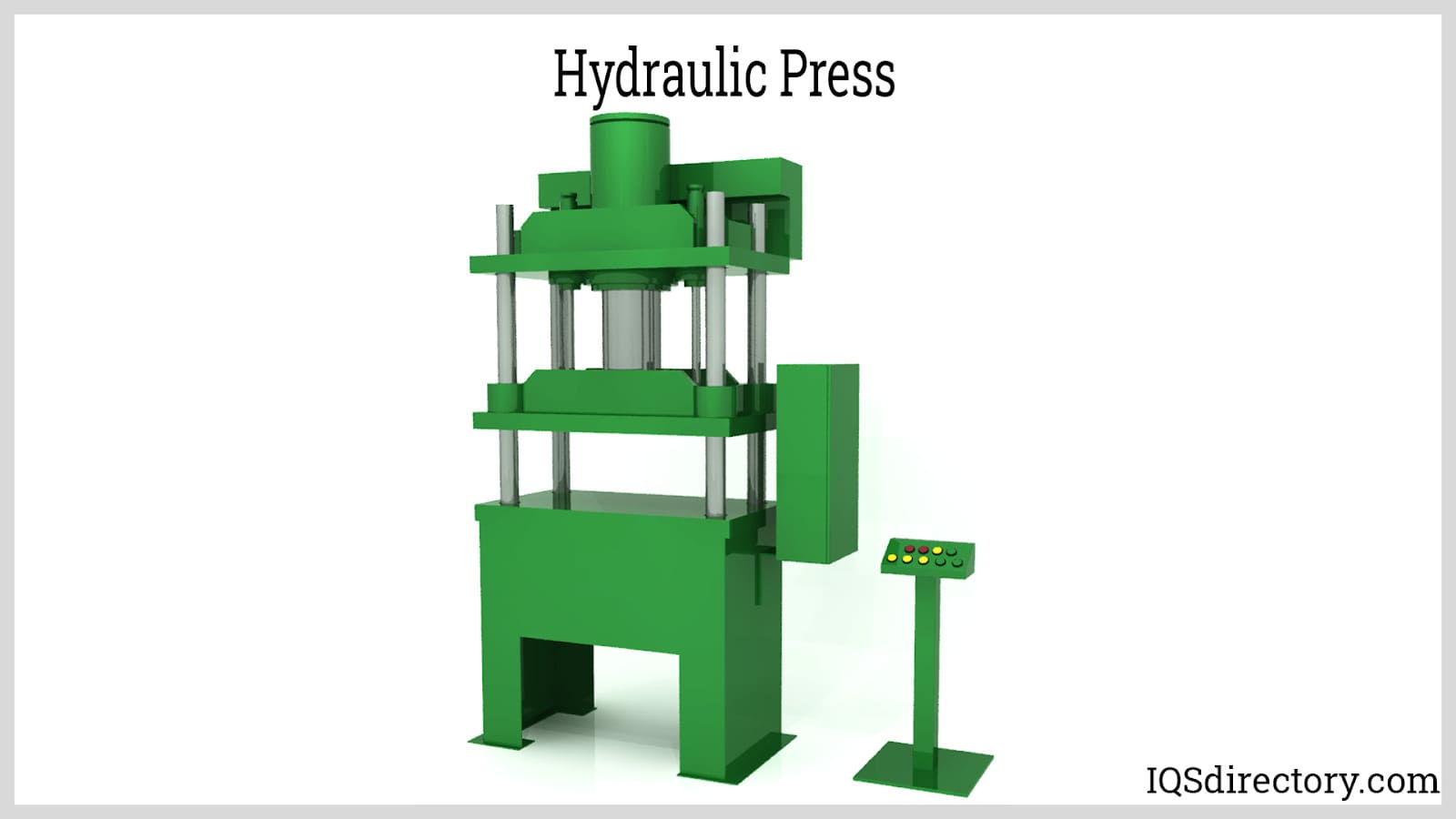

hydraulic press uses liquid static pressure to configure different materials into different shapes.

hydraulic press uses liquid static pressure to configure different materials into different shapes.

The hydraulic press uses the plunger displaces the fluid and extends the ram to shape the material.

The hydraulic press uses the plunger displaces the fluid and extends the ram to shape the material.

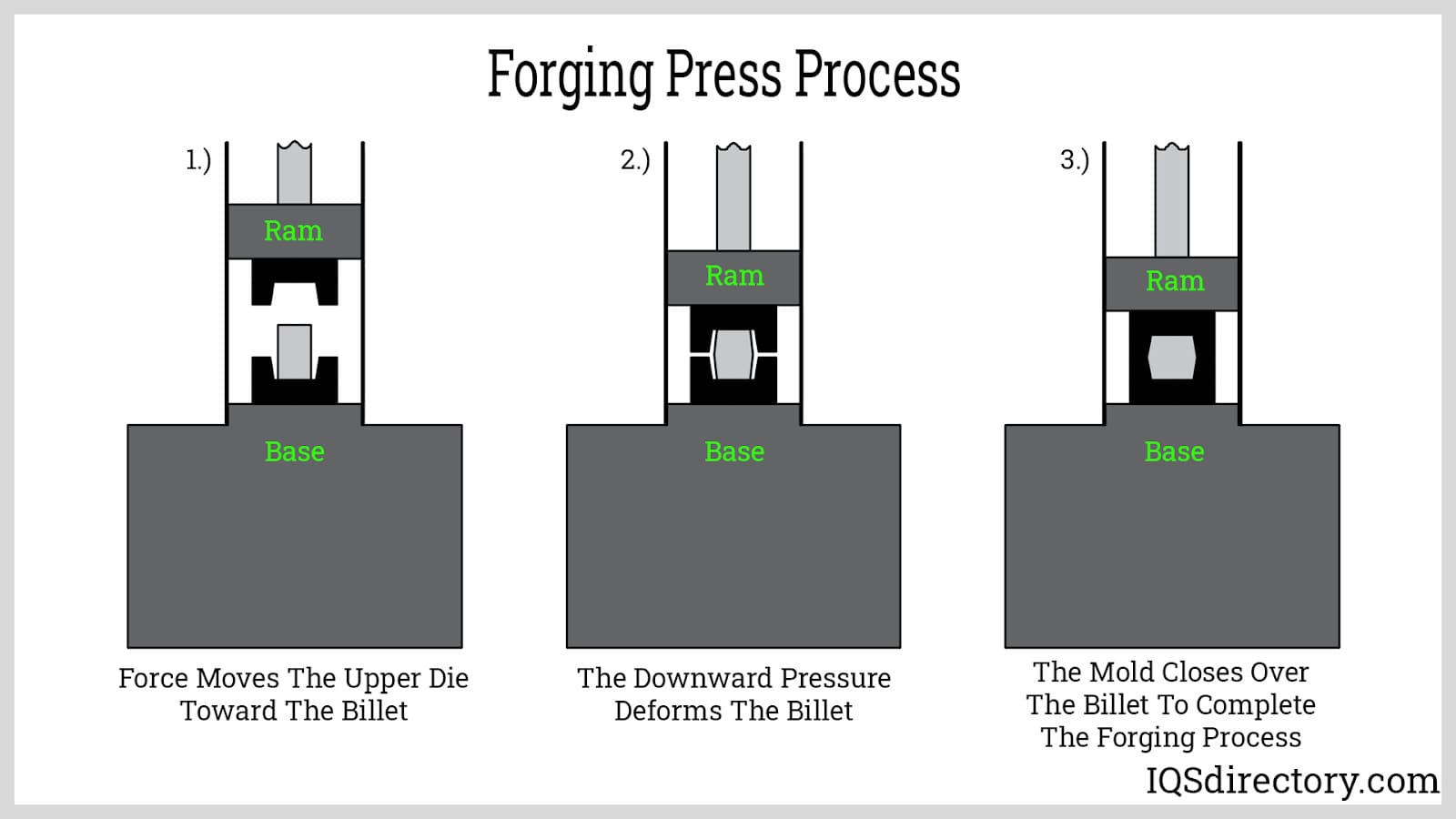

Forging presses use a vertical ram to apply gradual, controlled pressure to the workpiece inside a die.

Forging presses use a vertical ram to apply gradual, controlled pressure to the workpiece inside a die.

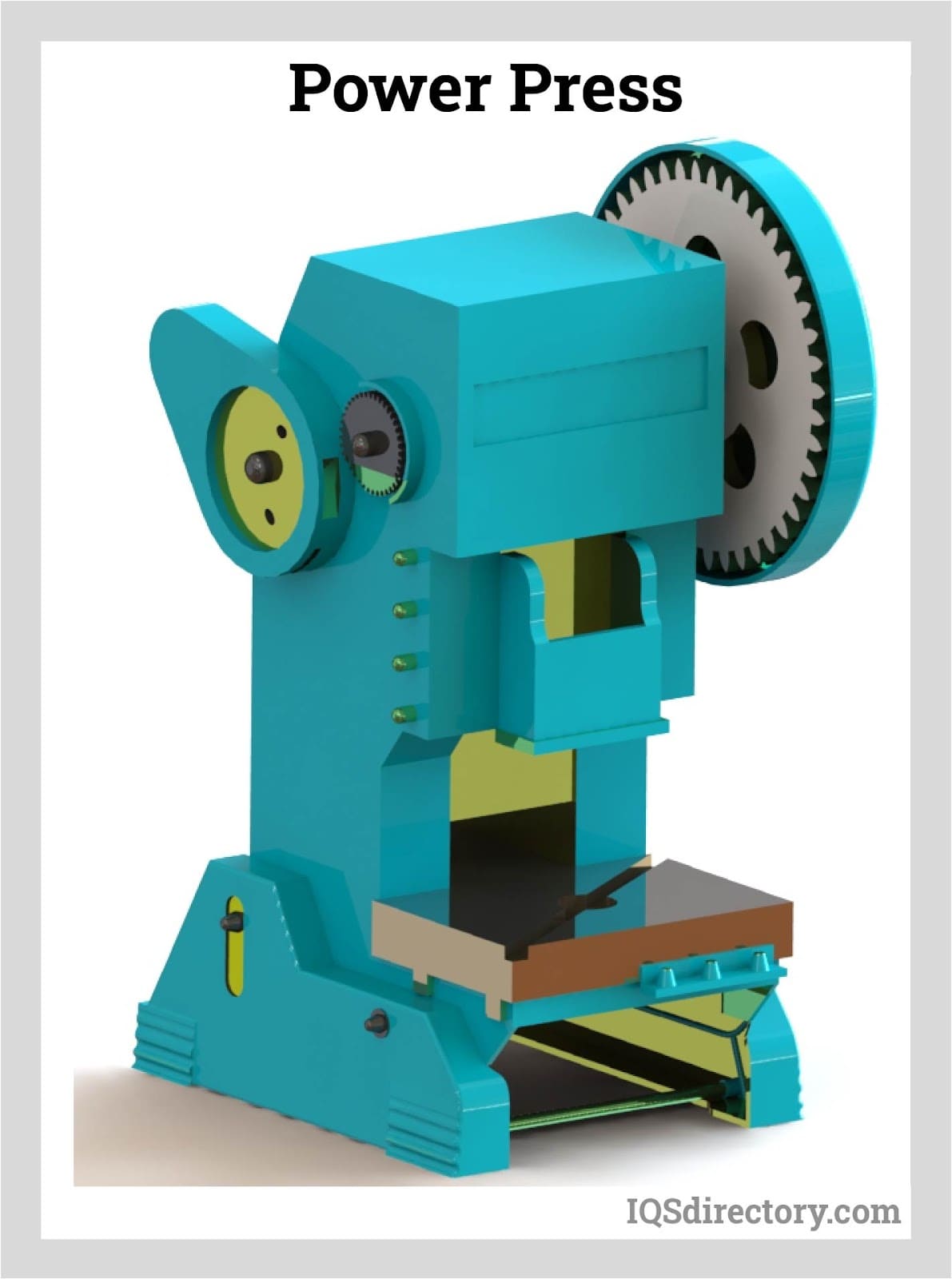

Power presses cut or shape any type of sheet metal to the required shape.

Power presses cut or shape any type of sheet metal to the required shape.

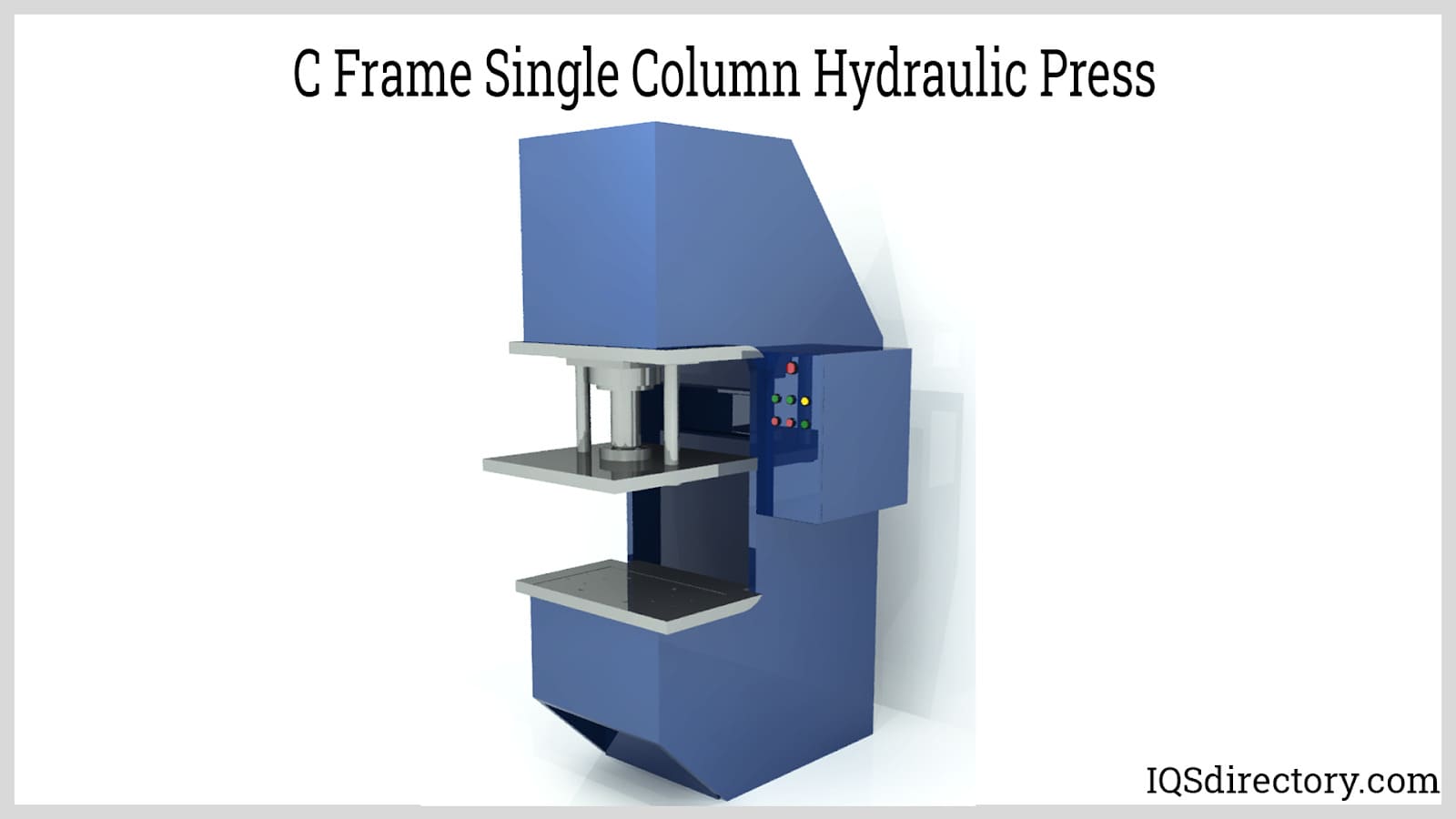

Single column C frame hydraulic presses have excellent rigidity, guide performance, speed, and exceptional precision.

Single column C frame hydraulic presses have excellent rigidity, guide performance, speed, and exceptional precision.

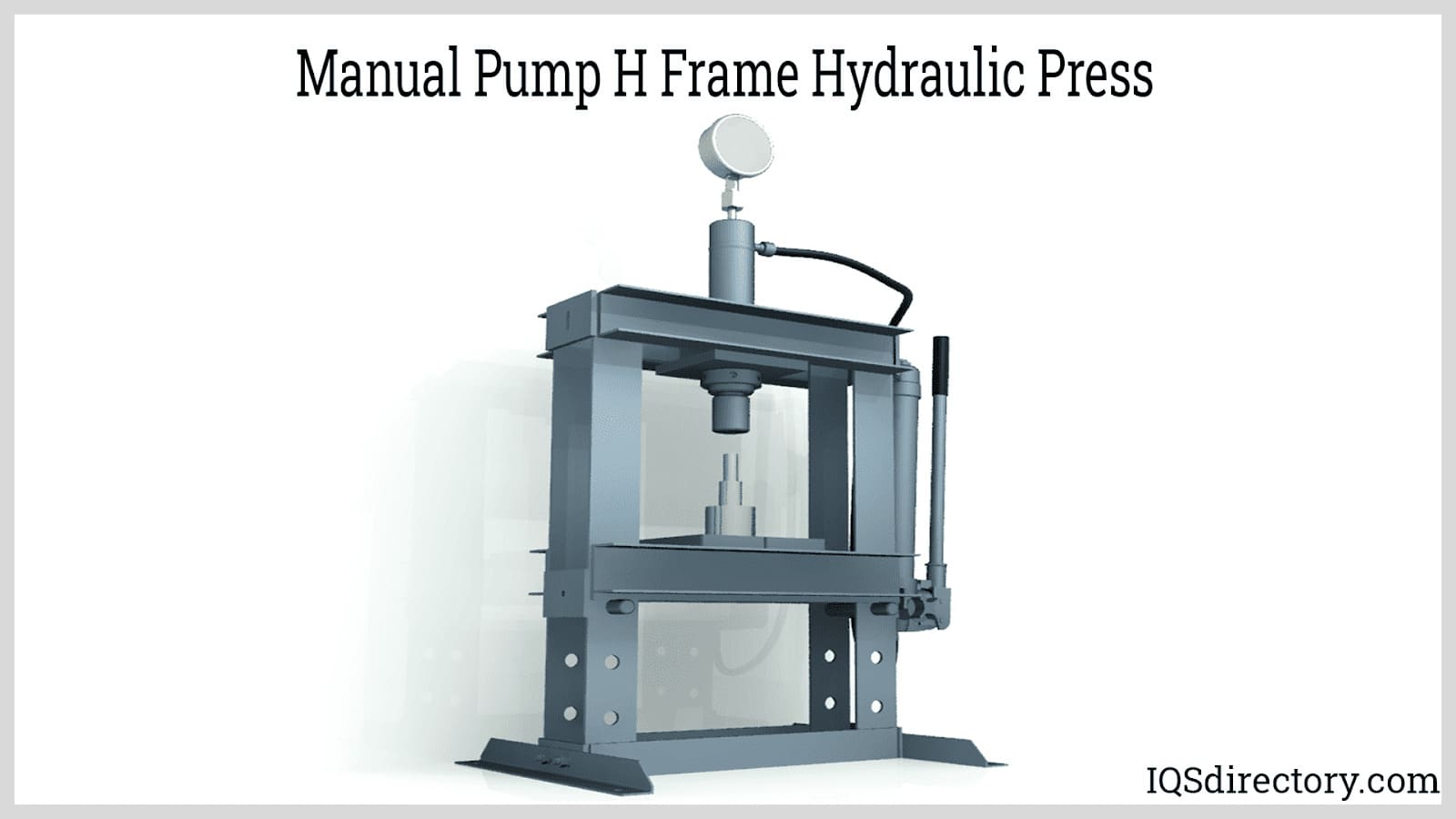

H frame presses can either be manual or automatic depending on the function.

H frame presses can either be manual or automatic depending on the function.

Types of Hydraulic Presses

- Arbor Presses

- Designed for high-pressure assembly, repair, and production tasks, arbor presses are widely used for seating, stamping, and removing bearings.

- Assembly Presses

- These presses apply immense pressure to securely fasten or assemble multiple parts together with precision and stability.

- C-Frame Presses

- Named for their compact, C-shaped frame, these presses are streamlined in size and typically used for single press applications.

- Compression Molding Presses

- These presses function by pressing two plates together to compress material within a mold, forming the desired shape.

- Forging Presses

- Hydraulically powered metal-forming machines that force metal blocks into specific shapes using molds, extreme force, and pressure—sometimes combined with heat—to achieve the final product.

- Platen Press

- A broad category of hydraulic presses that utilize a ram and a solid, stable surface to carry out a range of forming and shaping operations.

- Hydraulic C-Frame Press

- With a space-saving yet sturdy C-shaped frame, these presses handle a variety of industrial applications, including forming, straightening, blanking, punching, drawing, and riveting. They are available in both manual and automatic configurations.

- H-Frame Hydraulic Press

- Distinguished by their welded H-shaped frame, also known as 4-column presses, these machines can support multiple press applications simultaneously. They are commonly used for coining, crimping, bending, punching, and trimming, offering greater versatility than C-frame presses.

- Extrusion Press

- Designed for metalworkers and manufacturers, extrusion presses push material through a die to create a fixed cross-sectional profile, enabling precision extrusion of metal and other materials.

- Laboratory Presses

- Compact, single-run hydraulic presses primarily used in research laboratories for short production and test-run scenarios.

- Laminate Press (Laminating Press)

- Manually operated compression presses equipped with two plates—one for heating and one for cooling—allowing simultaneous heating and cooling to speed up the lamination process. These presses are commonly used to laminate polymers onto surfaces such as wood, metal, and paper.

- LIM Presses

- Specialized hydraulic presses designed for liquid injection molding, handling plastics that are formed through an injection process.

- Vacuum Press

- Engineered for specialized applications such as film application and material encapsulation in industries like electronics, credit card production, and ID card manufacturing.

- Stamp Press (Stamping Press)

- Used for shaping or cutting materials with a die, these presses are widely employed in metalworking and automotive industries for precision stamping operations.

- Transfer Press

- These presses automate the stamping and molding process by feeding flat plastic, rubber, or metal blanks into the press. Feed bar fingers then transport the part from one die to the next, making them ideal for high-efficiency manufacturing in medical and aerospace industries.

- Press Brake

- Used for bending and folding sheet metal, these machines typically feature two C-frames, a movable beam, and a bottom tool mounted on a table. Hydraulic press brakes operate with synchronized hydraulic cylinders that control movement, and when automated, they are classified as CNC press brakes.

- Hydraulic Forge Press (Forging Press)

- Exclusively used for metal forging, these presses force metal blocks into molds under extreme force, pressure, and sometimes heat. The process stretches the metal beyond its yield point without breaking it, making forge presses essential for vehicle manufacturing and other heavy-duty applications.

- Shop Press

- Primarily used in automotive repair, shop presses are versatile machines capable of removing, repairing, and setting bearings, bushings, U-joints, and more. They are also used for straightening bent parts, making them a practical choice for small garage businesses.

- Non-Hydraulic Presses

- A hydraulic press is a type of power press, but there are alternatives, including mechanical, electric, and pneumatic presses.

- Mechanical Press

- Utilizing a flywheel to store and release energy, these presses shear, punch, form, or assemble materials through tools or dies attached to slides or rams. Mechanical presses are categorized by the number of slides or rams they use—single, double, or triple action—and their stroke adjustability allows precise control over pressing operations.

- All-Electric Press

- A more recent innovation, these presses employ advanced drive systems where the ram is directly linked to the drive motor, providing efficient control over speed and eliminating hydraulic fluid variations, which can fluctuate due to temperature and time.

- Pneumatic Press

- Capable of performing operations similar to hydraulic presses, such as piercing, stamping, bending, and punching, pneumatic presses operate at speeds of up to 400 strokes per minute. They rely on compressed air for movement rather than rotary motion, reducing the number of moving parts compared to hydraulic and mechanical presses. However, pneumatic presses cannot achieve the extreme pressures that hydraulic presses can generate.

- Platen Presses

- Large-scale industrial hydraulic presses that use two heated steel plates to crush, mold, condense, or form materials into specific shapes.

- Power Presses

- Hydraulic-powered machines equipped with tools and dies for shearing, punching, and forming metal parts.

- Press Brakes

- Manual, mechanical, or hydraulic pressing machines that shape sheet metal through bending and folding. Hydraulic press brakes are controlled by synchronized hydraulic cylinders for precision metal forming.

- Stamping Presses

- Presses designed to stamp materials using specialized dies, enabling precision shaping and cutting operations in metalworking.

- Straightening Presses

- Designed to apply pressure to metal surfaces to straighten and align them with high accuracy.

- Tableting Presses

- Used for compressing powdered materials into uniform tablets or compacted shapes for pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

- Transfer Presses

- Hydraulic presses that automatically move parts from one stamping station to another using feed bar fingers, improving efficiency and consistency in high-volume production.

- Vacuum Presses

- Industrial hydraulic presses that utilize air pressure to create the necessary force for laminating and bonding applications, ensuring uniform adhesion of materials.

System Equipment Components of Hydraulic Presses

A hydraulic press is composed of essential components that form the foundation of a hydraulic system. In its basic form, a hydraulic press consists of a set of double-acting cylinders, pistons—also referred to as punches—hydraulic pipes, and a stationary anvil or die.

The system incorporates two cylinders of different sizes: a smaller one, known as the slave cylinder, and a larger one, referred to as the master cylinder. These cylinders work in tandem to generate the immense force required for pressing operations. The pistons serve as mechanical devices that create a plunging or thrusting motion, transferring hydraulic pressure throughout the system. The anvil or die, which is preformed to a specific design, determines the final shape of the substrate as it undergoes the pressing process.

Design and Customization of Hydraulic Presses

Hydraulic presses are engineered to handle extremely heavy loads, measured in tons. Manufacturers possess significant flexibility in designing presses that accommodate a wide range of load capacities. While some presses are built to withstand load limits as high as 3,500 tons, others can be designed for smaller-scale applications with load limits as low as 15 tons.

Constructed from robust materials such as stainless steel, high-strength steel alloys, aluminum, and brass, hydraulic presses are built for durability and longevity. These machines are available in both single and multi-station configurations.

Single-station presses feature a single set of press tools, including a die and punch, integrated into a worktable. In contrast, multi-station presses contain multiple sets of press machine tools. These tools can either perform identical operations on multiple materials simultaneously or execute different press operations as materials move progressively through various stages of production.

For enhanced customization, manufacturers can tailor a hydraulic press to specific requirements. They can modify the press ton limit, adjust length and folding dimensions down to the millimeter, customize die shapes, select the appropriate hydraulic fluid type, and implement additional modifications to optimize performance based on application needs.

Things to Consider When Purchasing a Hydraulic Equipment

Proper maintenance is essential for keeping hydraulic equipment operating efficiently and reliably. To ensure your machine remains in peak condition, consider these key preventative measures.

- Don’t Allow Leaks

- A leaky hydraulic system significantly reduces performance and efficiency. Operators should routinely inspect O-ring seals, the ram of the press, hydraulic lines, hose end fittings, and valve seats for any signs of leakage. Addressing leaks early prevents costly downtime and extends the machine’s lifespan.

- Don’t Exceed Load Limits

- Always ensure that the press operates within its designated load capacity. Applying a load heavier than the specified tonnage can place undue stress on the machine, leading to breakage, system failure, and potential safety hazards for operators.

- Keep a Well-oiled Machine

- To minimize wear and tear and ensure smooth operation, hydraulic machines must be adequately lubricated, particularly around seals. Additionally, it is crucial to use only the hydraulic fluid specified in the operator’s manual to maintain system integrity and performance.

- Check Pressure Build-up Speed

- A properly functioning hydraulic press should reach its working pressure within half a second to one second. If it takes more than two to three seconds to achieve the preset pressure, there may be an issue with the pump or relief valve. In many cases, the problem stems from an insufficient pump revolution rate. Valve-related issues, such as dirt in the hydraulic lines or an excessively wide valve opening, can also contribute to pressure buildup delays.

- Listen for Unfamiliar Machine Sounds

- Operators should promptly investigate any unfamiliar noises during operation. Banging sounds are often caused by valve shifts, while other abnormal noises may result from insufficient lubrication. Identifying the source early and addressing it can prevent serious mechanical failures.

- Check Electronic Machine Elements

- Hydraulic presses rely on various electronic components, including coils and relays, which have finite life cycles. Coils typically last for 3 million strokes, while relays are designed for around 1 million strokes. Regular replacement of these components reduces troubleshooting efforts and machine downtime. To streamline maintenance, use an hour meter and a non-resettable cycle counter to track machine performance and anticipate necessary replacements.

- Check Other Machine Elements

- Regular checks on machine fittings, wiring, and hoses are essential. Frayed hoses and improperly crimped fittings can lead to plumbing failures, which may compromise system efficiency and safety. Ensuring that all connections remain secure and in good condition is vital for sustained operation.

- Maintain Oil and Temperature During Operation

- One of the simplest ways to extend the life of a hydraulic press is by maintaining proper oil levels and ensuring oil cleanliness. Running the machine with low or contaminated oil can lead to damage and reduced performance. Regular oil sampling helps detect dirt and contaminants—if present, changing the filter is necessary to maintain system health.

- Temperature control is equally important. The optimal operating temperature for hydraulic presses is around 120°F. If temperatures rise beyond this threshold, system efficiency declines, leading to increased wear and potential failure. Using air and water coolers can help regulate temperature, but these units, especially radiators, require regular cleaning and maintenance to function effectively.

Choosing the Right Hydraulic Press Manufacturer

For optimal results from start to finish, it is essential to partner with a reputable hydraulic press manufacturer. Unfortunately, many subpar suppliers pose as high-quality manufacturers, making it challenging to distinguish reliable options. To avoid confusion and ensure you receive a top-tier product, refer to a verified directory of trusted manufacturers.

To simplify your search, we have compiled a list of reputable manufacturers. Visit their websites, compare their offerings, and evaluate their customer service. When you're ready, reach out with your specifications and assess their responsiveness, expertise, and overall service quality. By taking the time to compare and contrast, you can confidently choose a manufacturer that aligns with your needs.

Hydraulic Press Terms

- Actuator

- A mechanical device that transforms fluid power into linear or rotary motion, driving movement within a hydraulic system.

- Age

- The required waiting period between molding and evaluating the physical properties of a molded part.

- Backrind

- A molding defect occurring at the parting line, where material shrinkage results in an internal indentation.

- Bed

- The flat, stable surface that supports the material being processed during press operations.

- Bolster

- Plates attached to the rods that support the platens or any structure mounted to the bed of a press. Some bolsters are designed to be removable.

- Check Valve

- A valve that permits hydraulic fluid flow in only one direction, preventing backflow and maintaining system pressure.

- Compression Set

- The residual deformation left after a compressive force is removed. For example, when a molded material is pressed with a fingernail, the impression that remains over time is an example of compression set.

- Contact Gauge

- A hydraulic system component that automatically turns the system on or off when the pressure reaches preset thresholds.

- Cylinder Assembly

- The complete assembly within a hydraulic press that includes the cylinder, piston, ram, seals, and packing, all working together to generate force.

- Daylight

- The maximum vertical clearance a press can accommodate, measured from the underside of the ram to the top of the bolster when the ram is in its fully raised position.

- Die

- A precision tooling component in a hydraulic press used for shearing, punching, forming, drawing, or assembling materials.

- Gate

- The final opening through which injected material flows before entering a part cavity during the molding process.

- Heat Exchanger

- A system that circulates air or water to regulate oil temperature, ensuring consistent hydraulic system performance.

- Hydraulic Pressure

- The force exerted by pressurized fluid within a hydraulic system, enabling mechanical movement.

- Hydraulic Cylinders

- Devices that generate linear motion and force through the controlled application of pressurized hydraulic fluid.

- Hydraulic Pump

- A mechanical component that converts energy into pressurized fluid flow, delivering hydraulic power to the system’s components.

- Hydraulic Seals

- Specialized devices that prevent hydraulic fluid leakage while blocking contaminants from entering the system.

- Hydraulic Valves

- Critical components that control the flow and pressure of hydraulic fluid, directing movement and force within the hydraulic power system.

- Knockout

- A mechanism used to eject a finished part from the punch or die after processing.

- Low Pressure System

- A function allowing the press to operate continuously at no more than 10% of its maximum rated force, often used for preheating applications at reduced pressure.

- Platen

- A flat, rigid surface where the mold is attached. Hydraulic presses typically feature one stationary platen and one movable platen to facilitate pressing operations.

- Rod or Tie Rod

- A long, sturdy shaft that connects different press components, ensuring synchronized movement and structural integrity.

- Shut Height

- The vertical clearance above the bed when the ram is fully lowered, defining the maximum height of workpieces that can be processed.

- Sprue

- The main feed channel that directs molten material from the outer face of an injection or transfer mold into a single cavity or multiple cavity mold system.

- Stroke Control

- An adjustable feature that regulates the length of the press stroke, allowing operators to customize movement according to specific application needs.

- Throat Clearance

- The distance from the press frame behind the bed to the vertical centerline of the ram. This measurement determines the maximum width of workpieces that the press can accommodate.