Load Cells

Load cells are precision measuring devices designed to monitor and quantify forces related to compression, tension, and shear. As a type of transducer, they function by converting mechanical force into electrical signals, allowing for accurate measurement and analysis. In essence, a load cell—also referred to as a load monitor or load sensor—acts as a crucial tool for force detection across numerous applications.

From medical advancements to architectural engineering, load cells play an integral role in various industries, ensuring precise force measurement and structural integrity. Their electromechanical nature allows them to provide real-time data critical for safety, performance optimization, and quality control.

Measurements taken by load cells are typically expressed in newtons (N), meganewtons (MN), or kilonewtons (KN), reflecting the force being applied. These standardized units ensure consistency in measurement and enable accurate assessments in fields requiring precise load monitoring.

Load Cells FAQ

What does a load cell measure?

A load cell measures mechanical force—such as compression, tension, or shear—by converting it into an electrical signal. This allows precise monitoring of weight, stress, or pressure across industrial, scientific, and commercial applications.

How accurate are load cells?

Load cells offer exceptional accuracy, typically within 0.25%. This precision ensures dependable measurements for applications ranging from small-scale testing to industrial systems handling several thousand tons.

What are the main types of load cells?

Common load cell types include hydraulic, compression, tension, shear beam, and strain gauge models. Each type measures force differently, with specific designs suited for weighing, testing, and monitoring in industrial and laboratory settings.

What materials are used in load cell construction?

Load cells are typically made from stainless steel, alloy steel, aluminum, or tool steel. These materials provide durability, corrosion resistance, and strength to ensure accurate and consistent force measurement under demanding conditions.

Where are load cells used?

Load cells are used in industries such as manufacturing, construction, transportation, food processing, and pharmaceuticals. They ensure precise weighing, structural testing, and process monitoring for improved safety and efficiency.

How should load cells be installed?

Proper installation involves aligning the load cell correctly, securing it to a stable base, and following manufacturer guidelines. Correct mounting ensures long-term accuracy, prevents damage, and maintains reliable operation.

What certifications should quality load cells have?

High-quality load cells typically meet ISO, ANSI/J-STD-001B, or SAE AS9102 standards. Some also hold RoHS or NASA-STD-8739.3 certification, ensuring compliance with strict performance, safety, and environmental requirements.

The History of Load Cells

Modern load cells operate using a combination of the Wheatstone bridge equation and the strain gauge, two essential components that allow for precise force measurement. The Wheatstone bridge equation, originally developed in 1833 by Samuel Hunter Christie and later refined and popularized in 1843 by Sir Charles Wheatstone, introduced the concept of difference measurement. Today’s load cells typically incorporate four strain gauges arranged in a Wheatstone bridge configuration, enabling accurate and reliable force detection.

Before the advent of strain gauge technology, industrial weighing applications relied on mechanical lever scales. As technology progressed, hydraulic and pneumatic force sensors became the next evolution in force measurement. While the Wheatstone bridge equation had been established in the mid-1800s, it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that it was successfully combined with strain gauge technology to create the first effective load cells. The breakthrough came in the 1940s with the development of the first bonded resistance wire strain gauge, a pivotal moment that set the stage for future advancements.

As modern electronics advanced, the production of load cells became not only technically feasible but also economically viable. This innovation sparked rapid industry growth, transforming load cell technology into a critical component for industrial, commercial, and scientific applications. Since then, the field has continued to evolve, with ongoing advancements in materials, precision, and digital integration pushing the capabilities of load cells even further.

Advantages of Load Cells

One of the most significant advantages of load cells is their exceptional level of accuracy. With measurement precision reaching within 0.25%, load cells, sensors, and gauges reliably determine mass, weight, and pressure for loads ranging from the smallest measurements to several thousand tons. This high degree of accuracy ensures consistent and dependable results across a wide variety of industrial and commercial applications.

Another key benefit of load cells is their remarkable efficiency. They perform precise and linear measurements without experiencing discrepancies caused by environmental changes or variations in the medium in which they operate. This stability makes them an ideal choice for demanding applications where consistency and reliability are paramount.

Additionally, modern load cells are designed for longevity, with advanced engineering that ensures durability and sustained performance over time. Their robust construction incorporates a minimal number of moving parts, reducing wear and tear while minimizing the risk of mechanical failure. This not only extends the operational life of the load cell itself but also helps protect the machinery in which it is integrated, further enhancing overall system reliability and efficiency.

Design of Load Cells

Production Process

Load cell instruments are designed to precisely measure the actual mass of a material. Their production is based on fundamental principles of mass measurement under various conditions, including fluid pressure, elasticity, magnetic effects, piezoelectric properties, and zero environments. These principles allow load cells to deliver highly accurate and reliable measurements across different applications.

At the core of every load cell are two essential components: the sensing element and the circuit. The sensing element is most commonly a strain gauge, a small yet highly sensitive device composed of a coil that detects internal deformation and converts it into an electrical signal. This enables precise measurements of weight, force, tension, or strain. In some cases, the sensing element may be a piezoelectric sensor, which utilizes crystals to detect and convert mechanical stress into electrical output. The circuit, in turn, serves as the electrical network connecting these sensors, ensuring seamless signal transmission and measurement accuracy.

Load cells are designed to produce various types of output, including analog voltage, analog current, analog frequency, switch or alarm signals, and serial or parallel communication outputs. The most fundamental load cell configurations consist of four strain gauges forming the measuring circuit. However, for more intricate and high-precision applications, load cells can be equipped with up to thirty gauges, significantly enhancing their sensitivity and measurement capabilities.

Materials

The construction of load cells relies on various metallic materials, each selected for its unique properties and suitability for specific applications. Common materials used in load cell manufacturing include alloy steel, stainless steel, aluminum, and tool steel.

Each material offers distinct advantages in terms of strength, durability, and performance. Depending on the application, manufacturers choose materials based on key properties such as high strength, ease of machining, low weight, excellent thermal and electrical conductivity, high cryogenic toughness, malleability, high work hardening rate, corrosion resistance, and aesthetic appeal. These attributes ensure that load cells can withstand demanding industrial environments while maintaining precise measurement accuracy.

Design Considerations

The number of strain gauges within a load cell directly influences its sensitivity and ability to detect even the slightest measurement variations. More gauges allow for higher accuracy and finer resolution, making them ideal for applications requiring precision monitoring.

When determining the potential capacity of a load cell, manufacturers take several factors into account, including:

- The maximum force value the load cell must handle.

- The dynamic properties of the system, such as frequency response and reaction time.

- The impact of placing the transducer within the force path, ensuring minimal interference with measurement accuracy.

- The maximum extraneous loads the load cell may encounter, ensuring it remains stable and functional under varying conditions.

Proper mounting of load cells is equally critical to their performance and longevity. Several key factors must be evaluated before installation:

- Whether the load cell will be placed directly in the primary load path or if it will measure forces indirectly.

- Any physical constraints affecting size, orientation, and mounting configurations.

- The required level of accuracy, which dictates the design and placement of the load cell.

- Environmental factors such as temperature variations, humidity, vibrations, or exposure to corrosive elements, all of which can influence performance and may require specialized protection or materials.

Customization

Load cells come in a wide variety of sizes, shapes, and configurations, tailored to the specific demands of different industries. Their versatility allows them to be adapted for a vast range of applications, from aerospace and manufacturing to healthcare and construction. The ability to customize load cells ensures they provide optimal performance, durability, and reliability in even the most challenging operating environments.

Features of Load Cells

To make a load cell function, manufacturers apply it to a surface where the strain gauge or other sensor undergoes a physical change in shape or status in response to the applied force. The strain gauge detects this shift, measuring the stress, tension, or compression exerted on its surface with high precision. This fundamental process allows for accurate force measurement in various industrial and commercial applications.

The accuracy of the measurement output is guided by the principles of the Wheatstone bridge circuit. Once the circuit is properly configured, it is energized using stabilized voltage, known as excitation voltage. The system then detects the difference voltage, which is directly proportional to the applied load, and transmits it through the signal output. The sensor interprets this data and sends a corresponding signal to the machine’s LED display, where it is presented in a clear and understandable format for real-time monitoring and analysis.

For recording and transmitting data, load cell technology can be either analog or digital. In recent years, digital load cells have gained significant popularity over analog models due to their faster processing speed, superior accuracy, and improved resolution. When load cells are integrated into automated systems, they can actively monitor ongoing processes, detecting any inconsistencies or deviations. If an anomaly occurs, the load cell system can trigger an alarm or even initiate an automatic shutdown to prevent errors or equipment damage until the issue is corrected.

While other force and energy measurement tools exist, including elastic systems, vibration systems, and dynamic balance devices, none match the precision and technical sophistication of load cells. Unlike these more traditional measurement methods, which rely on mechanical principles and often introduce minor inaccuracies, load cells provide unparalleled accuracy, reliability, and responsiveness in force measurement and system control.

Load Cells Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

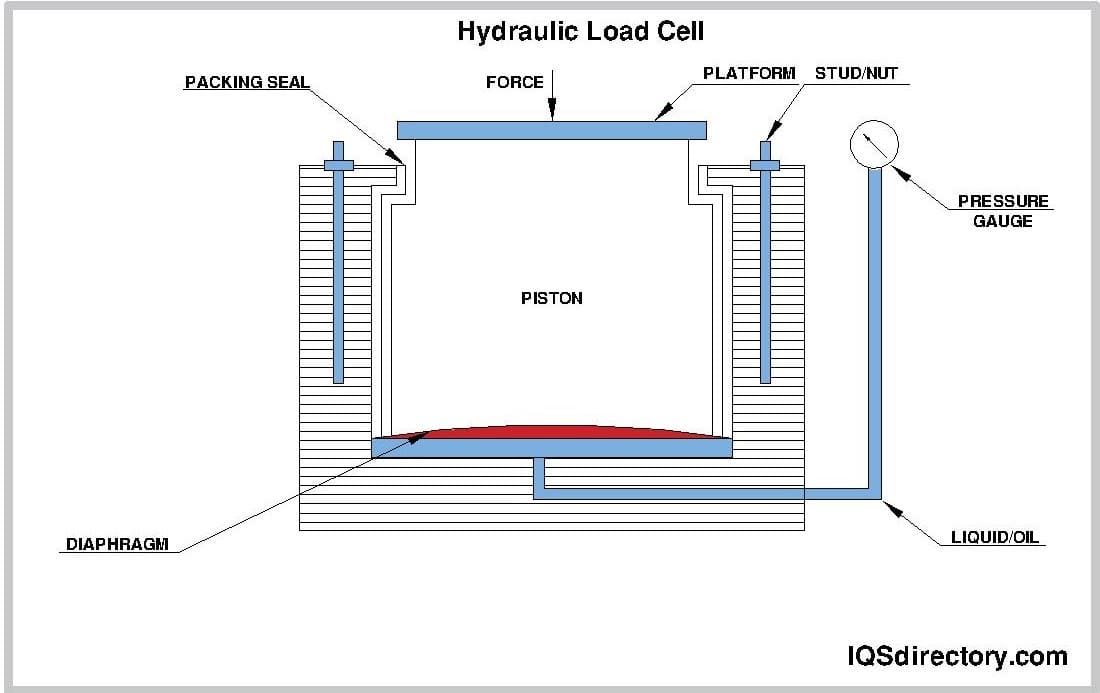

A hydraulic load cell measures a change in pressure in fluid substances.

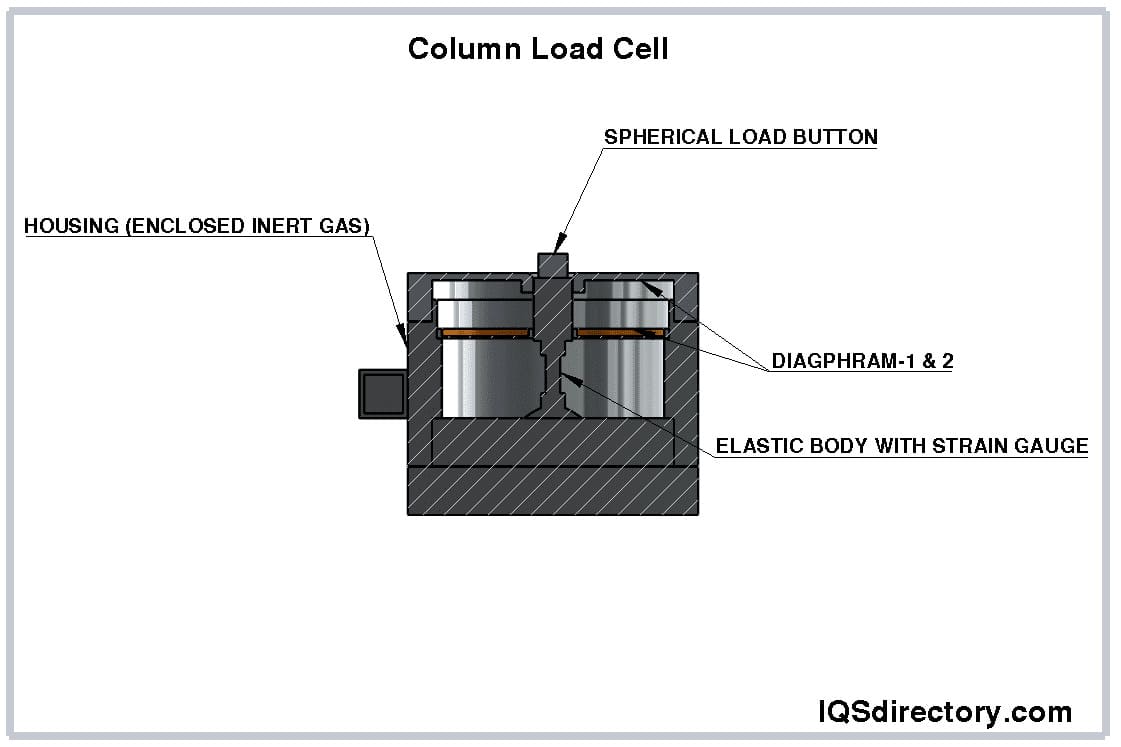

Column load cells measures compression forces and higher rates of load are necessary for the task.

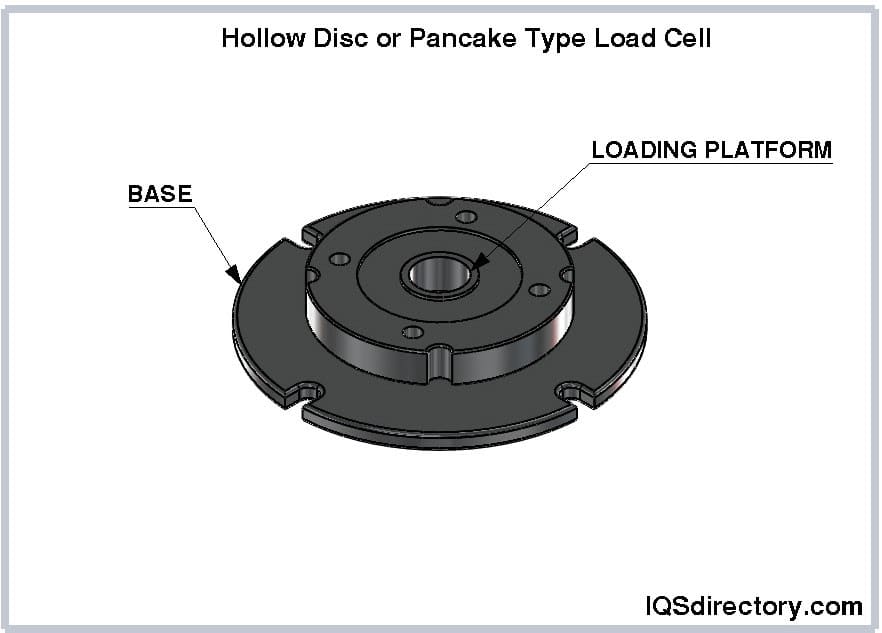

A pancake load cell used for both tension and compression measurements in materials.In addition to, component fatigue testing and axial force measurements.

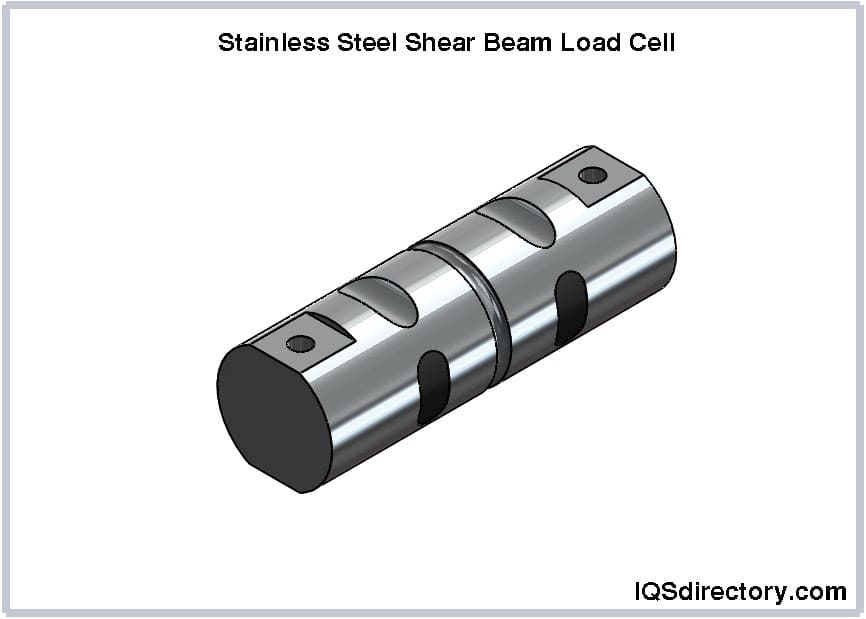

Beam load cells also known as bending load cells primarily used for industrial weighing.

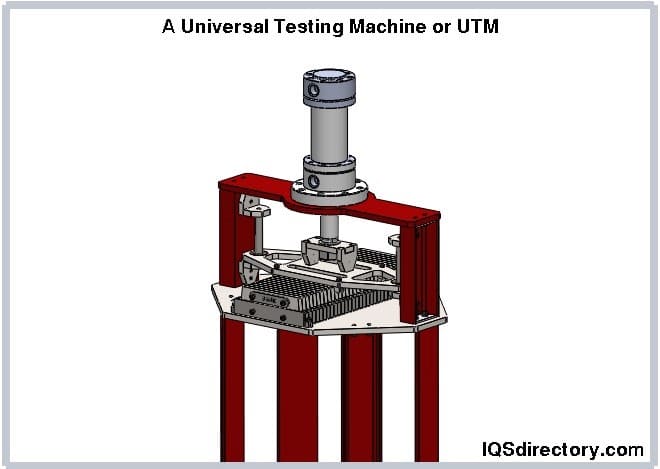

This equipment uses a load cell to test the tensile strength of products.

Types of Load Cells

Load cell manufacturing is dominated by three primary categories: load cells that measure force, compression, and tension. However, some advanced load cells are capable of measuring multiple forces simultaneously. The following are various types of load cells and their specific applications.

Hydraulic Load Cell

This type of load cell measures weight by detecting changes in pressure within an internal filling fluid. Hydraulic load cells are commonly used in tank, bin, and hopper weighing applications where highly durable and reliable force measurement is required.

Canister Load Cells

Designed for compact and cost-effective weighing applications, canister load cells accommodate a wide range of capacities. These load cells are frequently found in tanks, hoppers, and vehicle weighing systems due to their high strength and space-efficient design.

Compression Load Cell

Compression load cells measure straight-line pushing force along a single axis, commonly referred to as negative force. Because of their space-saving design and long-term stability, compression load cells are ideal for applications where compact solutions and precise weight measurement are necessary.

Tension Load Cell

Tension load cells measure pulling apart forces (positive force) along a single axis. Like compression load cells, tension models utilize strain gauge technology to ensure accuracy in force measurement applications.

Strain Gauge Load Cell

One of the most common types of load cells, strain gauge load cells have capacity ratings from 5 N to over 50 MN. These load cells provide high-resolution digital indicators and comply with industry force transfer standards for accurate and repeatable measurements.

Force Sensor

Also referred to as force gauges, force sensors utilize strain gauge technology to measure push-pull forces and assess flow rates in various applications.

Pressure Sensor

Similar to force sensors, pressure sensors are transducers designed to measure applied force, strain, and pressure in gaseous, liquid, and altitude-based applications. Many pressure sensors operate using piezoelectric technology, making them ideal for precise force measurement in dynamic environments.

Piezoelectric Crystal Force Transducer

These specialized load cells measure forces exerted on crystalline materials. When force is applied to a piezoelectric crystal, it generates electric charges, which are then measured and converted into a readable digital signal. Manufacturers often produce multi-component piezoelectric, hydraulic, and pneumatic load cells for high-precision applications.

Miniature Load Cell

Designed for precision measurement in compact applications, miniature load cells provide accurate readings in small-scale industrial, medical, and laboratory environments.

Donut Load Cell

Also known as thru-hole load cells, these devices measure compressive forces. Their smooth, round shape with a central hole allows for application parts or bolts to pass through. Donut load cells are commonly found in oil and gas pump applications where in-line force measurement is required.

Shear Beam Load Cell (S-Beam Load Cell)

This load cell consists of a straight block of material, with one end fixed and the other subjected to force. Members of the beam load cell family, also called bending load cells, are widely used in industrial weighing applications, including floor scales, tank and silo weighing, and vehicle weighing systems.

Low Capacity Transducer

These miniature transducers are utilized in medical testing equipment, wind tunnel sensors, weight counting machines, and residential scales. With a weight measurement range from 0.9 ounces to 150 pounds, low-capacity transducers are ideal for small-scale precision applications.

Mid Capacity Transducer

Capable of measuring loads between 200 and 20,000 pounds, mid-capacity transducers are well-suited for industrial and manufacturing applications, including industrial scales, truck weighing scales, bolt force measurement systems, and platform scales.

Micro Load Cells

A type of resistive load cell, micro load cells operate based on the principle of zero piezo-resistivity. When a load is applied, the sensor experiences a change in resistance and output voltage, allowing for high-accuracy measurements in delicate applications.

Multi-Axis Load Cell

Designed to measure multiple forces and moments simultaneously, multi-axis load cells contain multiple strain gauge bridges that enable precise force detection from different directions while minimizing cross-talk between forces.

High Capacity Transducer

Built for extremely heavy loads, high-capacity transducers are designed to measure forces exceeding 25,000 pounds. These load cells provide exceptional durability and reliability for applications requiring heavy-duty force measurement.

Specialty Transducer

Developed for specialized applications, specialty transducers are engineered to function in underwater, space, and extreme environmental conditions. Depending on their design, they may measure compression, tension, pressure, or other force parameters.

Pin Load Cell

A type of strain gauge load cell, pin load cells are constructed using load measuring pins embedded with strain gauges inside a central bore. These load cells are commonly used in anchors, shackles, sheaves, bearing blocks, and pivots, and are highly effective in underwater applications due to their sealed stainless steel construction and hermetically protected components.

Pancake Load Cells

Suitable for force measurement and weighing applications, pancake load cells can be used for both tension and compression. They are widely applied in materials testing and fatigue testing, where axial force measurement with high accuracy is essential.

Dynamometer Load Cell

A dynamometer load cell integrates load sensing technology with a dynamometer, a device used to measure force, torque, and power output. These load cells are primarily used for engine power measurement, though due to their high cost, they are typically employed only in applications where extreme precision is required.

Single Point Load Cell

Single-point load cells operate using a single load sensor and are commonly found in individual weighing applications, such as supermarket scales and other retail measurement devices. They are compact, highly precise, and designed for direct-force measurement.

Applications of Load Cells

Load cells, also referred to as load transducers, serve two primary functions: measuring physical quantities such as mass and converting force or energy into another form, including force, light, torque, or motion. Their ability to precisely detect and translate mechanical force into readable data makes them invaluable across multiple industries and applications.

Various types of load cells are widely used in mechanical testing, continuous system monitoring, and as integral components in devices such as industrial scales. Their versatility and reliability have made them essential in automation, sensor, and control systems across numerous sectors.

Industries in which load cells are used include:

Food Processing

Load cells ensure precise ingredient measurements and help maintain consistency in product distribution during packaging processes.

Industrial Warehousing

These sensors are used to determine the exact weight of loaded pallets, which is critical for inventory management, order fulfillment, and shipping logistics.

Building and Construction

Load cells play a key role in testing structural materials, such as beams, for tension and overall structural integrity, ensuring safety and compliance with engineering standards.

Transportation

Railcars and trucks rely on load cells for accurate weighing, improving safety, efficiency, and regulatory compliance in freight transportation and logistics.

Research Laboratory and Pharmaceutical Production

In scientific and pharmaceutical settings, load cells are used in precision weighing equipment, calibration systems, and fatigue testing to ensure product consistency and experimental accuracy.

Beyond these industries, load cells can be found in a variety of specialized applications, including security systems, electrical weighing scales, personal scales, thermometers, defense sector machinery, industrial automation, submarine pressure sensing, and material testing. Their adaptability and accuracy make them indispensable for applications requiring precise force measurement and monitoring.

Load Cell Installation

Each load cell is uniquely designed and requires careful handling during installation to ensure optimal performance and longevity. Proper installation is crucial for maintaining accuracy, preventing damage, and ensuring reliable operation within its intended application. To determine the precise installation procedure for your specific load cell, consult your supplier, who can provide detailed guidance tailored to your model and operational requirements.

Standards and Specifications for Load Cells

No matter your industry, ensuring the quality of your load cell is essential. To guarantee reliability and precision, we recommend sourcing load cells from a manufacturer with ISO certification, as this ensures compliance with internationally recognized quality management standards. Additionally, look for load cells that meet ANSI/J-STD-001B and/or SAE AS9102 standards, which set stringent requirements for manufacturing consistency and performance.

Before bringing a load cell into your facility, confirm that it has undergone insulation resistance testing, a critical quality control step that verifies its safety and operational readiness. This test helps prevent electrical failures and ensures the load cell performs as expected under various conditions.

For products intended for use in the European Union, request RoHS certification to confirm compliance with environmental and safety regulations regarding hazardous materials. Beyond these general standards, additional industry-specific certifications may be required. For example, if a load cell is to be used in NASA applications, it must comply with NASA-STD-8739.3, which governs high-reliability interconnections in aerospace and spaceflight environments. Ensuring compliance with the appropriate certifications guarantees that your load cell meets the highest standards for performance, safety, and longevity.

Things to Consider When Choosing Load Cells

In today's society, the accuracy and efficiency of balancing scales have reached their highest levels. Scientific advancements now allow weight measurements to be assessed down to the hundredth and thousandth of a decimal. When using an electric scale, the likelihood of inaccuracy is virtually eliminated.

However, several factors, whether intentional or unintentional, can influence a scale’s accuracy. Understanding these factors ensures consistent and precise weight measurements.

Correctness of Load Cell

The accuracy of a balancing scale is entirely dependent on the quality of its load cell. To achieve precise results, it is essential to use a machine built with high-quality load cells. The performance and correctness of the load cells determine how accurately the scale measures weight. Choosing a scale with subpar load cells increases the risk of inaccuracies, making it crucial to invest in a well-manufactured system.

Load Application Process

When determining the G-factor of an item, proper load application is essential. The weight must be placed correctly on the scale, following the guidelines provided in the user manual. This process is relatively simple for low-capacity home or small business scales but becomes more complex with heavy loads. For larger weights, careful loading and unloading are necessary to prevent strain on the scale’s components. Ensuring the load is evenly distributed and aligned with the designated load points is crucial for accurate weight measurement and preventing strain gauge errors.

Weighing Environment

External environmental factors can significantly impact the accuracy of a scale, particularly when weighing heavy loads. Wind, temperature fluctuations, and pressure differentials can all introduce inconsistencies. That is why selecting a stable, controlled environment for installing mid- and large-level balancing scales is important. Eliminating environmental interferences ensures precise weight readings and prevents discrepancies caused by external variables.

Installation and Use of Weight Controller

Improper installation is one of the leading causes of inaccurate weight readings and inefficiencies in material assessment. Ensuring that the scale is correctly balanced within its surroundings is crucial. Carefully following the installation guide provided by the manufacturer helps prevent errors that could compromise accuracy. Additionally, implementing a weight controller system can reduce noise and mitigate external disturbances that might affect mass measurement.

For optimal results, a high-quality load cell that meets the application’s specific requirements is essential. Finding the right manufacturer is the first step in securing a reliable and precise weighing system. The best approach is to browse the websites of reputable companies, compare their offerings, and reach out with your specifications. When selecting a manufacturer, confirm their ability to meet your timeline and budget while adhering to your technical requirements. Strong customer service and a willingness to collaborate are key indicators of a manufacturer’s reliability and commitment to delivering high-quality load cells.

Proper Care for Load Cells

Load cells are highly sensitive instruments, requiring careful handling to maintain their accuracy and longevity. Proper maintenance and usage ensure consistent performance while preventing damage.

- To avoid high voltage surges, always use a stable and regulated power supply. Electrical fluctuations can interfere with measurement accuracy or cause permanent damage to the load cell’s internal components.

- Never remove or tamper with sensor covers. These protective enclosures safeguard the delicate internal components from dust, debris, and accidental impact. Any unauthorized adjustments can compromise performance and void warranties.

- Monitor the temperature environment to ensure it remains within the load cell’s specified operating range. Excessive heat or extreme temperature fluctuations can alter sensor readings and reduce the reliability of measurements over time.

- Handle load cell cables with care—avoid pinching, kinking, yanking, or overbending them. Damaged cables can disrupt signal transmission and lead to inaccurate readings or complete sensor failure. Ensuring proper cable management will extend the load cell’s operational lifespan and maintain consistent performance.

Accessories for Load Cells

While load cells are largely self-sufficient and do not require many additional components, a few key accessories enhance their functionality and performance. These include load cell bases and load cell buttons, both of which contribute to stability and accuracy in various applications.

Load cell bases provide a secure mounting option by allowing end-users to bolt their load cells onto a stable, reliable surface. This ensures consistent performance by minimizing external movement or interference. With a properly mounted base, the load cell can operate efficiently from a simple and dependable interface.

Load cell buttons are particularly useful in applications where misalignment of the applied load may occur. These components help distribute force evenly, ensuring accurate weight measurement and reducing stress on the load cell. By addressing potential alignment issues, load cell buttons improve precision and extend the operational lifespan of the system.

Load Cell Terms

Axial Load

The force applied along the length of or parallel to the primary axis, sharing a common axis with it.

Calibration

The process of comparing a load cell's output against standard test loads to ensure accuracy.

Creep

The gradual change in a load cell’s output over time while under a constant load, assuming environmental conditions and other variables remain unchanged.

Dead Volume

The internal volume within the pressure port of force sensors or transducers at room temperature and barometric pressure.

Deflection

The change in length along the primary axis of a load cell between no-load and rated-load conditions.

Diaphragm

The membrane component of force sensors that deforms under pressure-induced displacement.

Drift

An unintentional and unexpected change in a load cell’s output while under a constant load.

Driveline Shaft

A steel tube with a universal joint at each end, transferring torque from the output of the transfer case to the axle in load cell applications.

Eccentric Load

A force applied parallel to the primary axis of a load cell but without a common axis, potentially causing inaccurate readings.

Electrical Excitation

The current or voltage supplied to the input terminals of a transducer to generate a measurable output.

Flush Diaphragm

A sensing device positioned at the very end of a transducer, with no pressure port, ensuring direct force measurement.

Full Scale

The maximum measurable load that a specific load cell is designed to handle for a given application or test.

Full Scale Output

The numerical difference between the lowest output and the rated capacity of a load cell.

Hysteresis

The largest difference in load cell output for the same applied load, measured once when increasing the load from zero and again when decreasing the load from rated capacity.

Input Impedance

The resistance measured across the excitation terminals of a transducer at room temperature, with no applied load and open-circuited output terminals.

Load

The force, weight, or torque exerted on a transducer, load cell, or force sensor.

Load Cell

A device designed to measure force, typically featuring a rounded top surface where the load is applied.

Measured Media

The physical property or condition that a load cell measures, such as force, acceleration, mass, or torque.

Piezoresistance

The change in electrical resistance due to applied strain on a load cell’s diaphragm.

Primary Axis

The geometric centerline along which a load cell is specifically designed to bear a load.

Pull Plate

An attachment to a load cell that ensures tension or compression forces are applied directly along its centerline through a threaded center hole.

Safe Overage

The maximum pressure or load a transducer, load cell, or force sensor can withstand without causing permanent damage or affecting performance specifications.

Shear

A force that acts parallel to opposing stresses within a load cell, tending to divide an object along a given plane.

Strain Measurement

The ratio of the change in length of a structure when force is applied compared to its original length, providing insight into material deformation and stress distribution.

Torque Sensor

A device that measures the rotary movement of a force or a system of forces causing rotation within an engine or mechanical system. Torque sensors gauge the torque transferred along the drive-line axis at the point where the sensor is positioned, ensuring accurate monitoring of rotational force in automotive, aerospace, and industrial applications.

Zero Balance

The output signal of a load cell at rated excitation with no load applied. This value is typically expressed as a percentage of the rated output and serves as a reference point for calibration and accuracy verification.

More Load Cells

Load Cell Manufacturers