Magnets

Magnets are metallic composites, typically composed of ferrous metal, that generate a magnetic field. This field enables them to attract magnetic objects while also influencing other magnets, either drawing them closer or pushing them apart. The vast array of magnets available today varies in magnetic strength, heat resistance, corrosion tolerance, and permanence, making them suitable for diverse applications.

Magnets fall into two primary categories: non-permanent and permanent. Non-permanent magnets, or electromagnets, rely on an external power source and activate their magnetic properties through electrical currents. They serve critical roles in industrial applications, including solenoid valves, AC and DC motors, biomagnetic separation, and transformers. Permanent magnets, in contrast, maintain their magnetism without an external power source. These include ceramic magnets (ferrite magnets), alnico magnets, and rare earth magnets. Ceramic magnets offer lower magnetic power and are brittle, yet they remain a cost-effective option for non-structural uses such as motors, magnetic chucks, and tools. Rare earth magnets, though more expensive to produce, provide significantly stronger magnetic fields and superior retention of magnetism. Their power makes them essential in industrial lifting and holding applications, as well as in motors, speakers, sensors, testing instruments, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) systems.

Magnetic assemblies integrate various types of magnets—including electromagnets, ceramic, alnico, and rare earth magnets—into specialized tools for lifting, holding, or separating metallic materials. By combining different magnet types, these assemblies enhance overall magnetic force, optimizing performance for industrial and manufacturing applications. They play a vital role in lifting metal parts and sheet metal, securing components in place, separating materials, and facilitating water treatment processes. Both permanent and electromagnetic magnet assemblies are indispensable in fields such as automotive, aerospace, electronics, and biomedical technology. These applications range from beam control, software disk programming and erasing, and MRI technology to welding equipment, ignition timing systems, electric motor activation, sound speakers, and blood testing and separation. Various magnet types serve industry-specific needs—sheet magnets, for instance, are flexible ferrite-plastic composites extruded into sheets for use in automotive and consumer applications. These can also be cut into rubber-based magnetic strips. Meanwhile, bar magnets, commonly made from ferrite metal, remain one of the most widely used magnet forms.

When manufacturing magnets, several key properties must be considered, including porosity, ease of fabrication, retention of magnetism under heat and corrosion, magnetic strength, and overall cost. No single magnet type excels in all these areas, as each material composition offers distinct advantages and trade-offs. Ceramic magnets, composed of sintered ceramic powder, iron oxide, and either strontium or barium, can be compressed, extruded, or sintered into various shapes. The resulting material is a cost-efficient, brittle, porous, charcoal-gray ceramic often shaped into arcs for motors, discs, and blocks for lifting and holding applications. Due to their porous nature, ceramic magnets are highly susceptible to corrosion and lose magnetism under high temperatures. Alnico magnets, made from aluminum, nickel, cobalt, and iron, share similarities with ceramic magnets but offer greater durability, superior shape retention, and higher magnetic resistance.

Rare earth magnets, including neodymium and samarium cobalt magnets, surpass ferrite and alnico magnets in power. Their strength stems from the partially filled outer f-electron shells of the rare earth lanthanide elements neodymium and samarium. Neodymium magnets, composed of neodymium, iron, and boron, exhibit the highest magnetic pull of any magnet type. However, they have limited heat and corrosion resistance and begin to lose magnetism at temperatures above 200 degrees Celsius. To counteract their brittleness, neodymium magnets are frequently nickel-coated for protection. Samarium cobalt magnets, a combination of samarium and cobalt, offer superior resistance to demagnetization and corrosion while maintaining thermal stability up to 550 degrees Celsius. Their high-temperature endurance makes them ideal for motors and medical tools. However, the scarcity of rare earth materials and the lengthy extraction process from lanthanide ores render rare earth magnets significantly more expensive than their non-rare earth counterparts.

Magnet FAQs

What are the main types of industrial magnets?

Industrial magnets include permanent, temporary, electromagnets, and superconducting magnets. Permanent magnets retain magnetism without power, electromagnets require electric current, and superconducting magnets offer the highest power when cooled to extremely low temperatures.

What are rare earth magnets made from?

Rare earth magnets are composed of lanthanide elements such as neodymium and samarium. Neodymium magnets combine neodymium, iron, and boron, while samarium cobalt magnets combine samarium and cobalt, providing exceptional magnetic strength and heat resistance.

How are ceramic magnets used in industry?

Ceramic magnets are cost-effective materials made from iron oxide and strontium or barium carbonate. They are widely used in motors, magnetic chucks, tools, and lifting applications, though they are brittle and less heat-resistant than rare earth types.

Why are magnets important in manufacturing and recycling?

Magnets enable efficient sorting and separation of ferrous materials, reducing contamination and maintenance costs. They are essential in recycling centers, waste management, and material handling for their ability to quickly extract magnetic components from mixed materials.

What are the benefits of using magnets in industrial settings?

Industrial magnets reduce mechanical wear, enhance safety by collecting metal debris, and prevent contamination in food, pharmaceutical, and chemical manufacturing. They improve efficiency in lifting, sorting, and separation operations across multiple industries.

How should industrial magnets be handled safely?

Safety precautions include wearing gloves and goggles, avoiding contact with electronics or pacemakers, and properly shielding magnets during transport. Strong magnetic fields can cause injuries or interfere with sensitive devices if mishandled.

What factors affect magnet performance and durability?

Magnet performance depends on material composition, temperature resistance, and protective coatings. Environmental conditions like heat, humidity, and corrosion can degrade magnetic strength, so coatings and proper design are essential for longevity.

When should a magnet be inspected or replaced?

Magnets used for lifting or holding heavy materials should be inspected regularly for degradation or loss of magnetic force. Routine testing prevents accidents, and manufacturers can provide guidance on replacement intervals and performance checks.

Notable Applications of Industrial Magnets

-

Sorting

The fundamental principles of magnetism enable the separation of ferrous from non-ferrous materials and magnetic from non-magnetic materials, providing an essential function in recycling, waste management, and material processing industries.

Magnetic Sweepers

A straightforward yet effective use of magnets, these tools attract and collect loose ferrous components to enhance safety and prevent the loss of valuable materials in industrial and commercial environments.

Imaging Devices

Magnets play a crucial role in advanced medical and scientific imaging technologies, allowing for the visualization of areas and structures that would otherwise remain unseen. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and other scanning devices rely on magnetic fields to generate detailed images for diagnostic and research purposes.

Lifts

Industrial lifting applications leverage magnetic pick-up technology to securely lift, hold, and transport ferrous materials with minimal moving parts, improving efficiency and reducing mechanical wear in handling operations.

Data Storage

Magnetic fields serve as the foundation for credit card functionality, hard drives, and various other digital storage media. The precise arrangement of magnetic particles enables the encoding and retrieval of data, making magnetism integral to modern information technology.

Household Goods

Magnets are widely used in everyday household applications, including refrigerator magnets, cabinet latches, and door closures, offering convenient and reliable fastening and storage solutions.

Maglev Trains

By utilizing repelling magnetic forces, magnetically levitated (maglev) trains achieve nearly frictionless motion, enabling high-speed transportation with increased efficiency and reduced maintenance compared to traditional rail systems.

Seals

Magnetic seals provide secure closure mechanisms in refrigerators and other storage containers, ensuring airtight insulation and preventing energy loss while maintaining convenient access.

Generators and Electric Motors

Magnets form a fundamental component in electric motors and generators, where they facilitate the conversion of electrical energy into mechanical motion or vice versa. The type and configuration of the magnet determine the efficiency and performance of the motor assembly.

Electronics

A vast range of electronic devices rely on magnetism for various proprietary functions. Cathode ray tube (CRT) televisions, for example, use magnetic fields to deflect electron beams and create images, while many modern devices incorporate magnets for speakers, sensors, and wireless charging technologies.

History of Magnets

The use of natural magnets dates back to ancient civilizations, with early records indicating that Chinese mariners employed the properties of natural magnetite to develop the first compasses for navigation. While magnets have been utilized for centuries, the scientific study of magnetism began much later. In 1600, William Gilbert conducted some of the earliest systematic experiments on magnetism, uncovering methods for producing artificial magnets and observing the effects of temperature on magnetic properties.

The widespread industrial application of magnets only emerged after significant advancements in electronics and magnetism, propelled by renowned physicists such as J.J. Thomson. Although rudimentary electromagnetic generators and other magnet-based technologies were present by the early 19th century, it wasn’t until the 20th century that scientific understanding progressed enough to enable the diverse range of modern magnetic applications.

Some of the most powerful industrial magnets, known as rare earth magnets, were not developed until the 1970s and 1980s. Meanwhile, superconducting magnets were first theorized in 1911, yet it took until 1955 to successfully produce them. More recent advancements in superconductors and electronics have further expanded the use of magnets, accelerating their integration into cutting-edge technology and industrial processes.

Basic Categories of Industrial Magnets

-

Permanent Magnets

These are the most commonly used magnets, retaining their magnetism indefinitely without requiring an external power source. They are essential in countless applications, from industrial machinery to consumer electronics.

Temporary Magnets

These materials exhibit magnetic properties only when exposed to a strong external magnetic field. Typically composed of simple ferrous materials, temporary magnets are widely used in electronic devices where magnetic effects are needed intermittently.

Electromagnets

Generated by an electric current, electromagnets rely on a continuous power supply flowing through tightly wound coils of wire. Unlike permanent magnets, they can be switched on or off as needed, making them integral to various electronic devices, industrial lifting systems, and electromagnetic applications.

Superconductors

Functioning similarly to electromagnets, superconducting magnets operate without a metal core and require extreme cooling to reach superconducting states. As the most powerful type of magnet, they are indispensable for high-intensity applications, including industrial magnetic separator machines, MRI scanners, and advanced scientific research.

Benefits of Using Industrial Magnets

Industrial magnets are often designed for highly specialized applications, making it difficult to generalize their advantages. However, their unique properties provide consistent benefits across numerous industries.

Reduced Maintenance Costs

Magnets help lower maintenance expenses in several ways. By attracting and collecting ferrous debris, they prevent damage to mechanical components, reduce the risk of punctured tires in industrial settings, and enhance workplace safety. Additionally, magnetic lifting and holding systems minimize mechanical wear and tear by reducing reliance on moving parts.

Contamination Prevention

Many manufacturers use industrial magnets to extract ferrous and magnetic contaminants from production lines and storage areas. This is particularly crucial in industries such as food processing, pharmaceuticals, and chemical manufacturing, where contamination can compromise product integrity and safety.

Efficient Sorting and Separation

One of the simplest yet most effective applications of industrial magnets lies in their ability to quickly distinguish between ferrous and non-ferrous materials. Magnetic sorting systems streamline production and recycling processes, eliminating the need for time-consuming manual separation and improving overall efficiency.

Industrial Magnet Accessories

Most industrial magnets function as integral components within larger assemblies or machinery, minimizing the need for standalone accessories. However, smaller magnets used in raw form can benefit from additional enhancements to improve performance and longevity.

Covers

Protective covers shield magnets from physical damage, help insulate nearby electronic components when the magnet is not in use, and prevent unintended demagnetization.

Ferrous Components

Small ferrous elements, such as steel-and-nickel discs, can be paired with magnets for a wide range of applications, enhancing magnetic performance or serving as attachment points.

Connectors and Adhesives

Specialized connectors and adhesives enable magnets to be securely attached to other materials, ensuring proper alignment and stability in various applications.

Design Factors to Consider for Industrial Magnets

When selecting an industrial magnet, several critical design considerations will influence performance and cost-effectiveness.

The first factor is determining either the exact type of magnet required or specifying key attributes such as strength, durability, and permanence. A clear understanding of these characteristics allows suppliers to make informed recommendations.

Shape is another essential consideration. If a specific shape is necessary for the intended application, it should be specified early in the design process. However, if shape is not a concern, opting for standard or easily manufactured forms can reduce production costs.

Coating requirements should also be evaluated, especially for magnets exposed to harsh conditions. Protective coatings help prevent wear, corrosion, and chemical damage, extending the magnet’s lifespan in demanding environments.

Environmental factors must also be taken into account, as different magnets respond differently to temperature variations. Additionally, certain component metals, such as iron, may be prone to rust in humid conditions unless treated with protective coatings or specialized finishes.

Magnet Safety Considerations

-

Goggles

When handling heavy-duty magnets, protective goggles are essential for several reasons. These magnets can shatter or break other materials, sending sharp fragments flying. In machining and industrial applications, they may also generate sparks or burns, posing additional hazards to the eyes.

Gloves

Improper handling of heavy-duty magnets can result in abrasions, sprains, and even broken bones due to their intense magnetic force. Additionally, shattered magnet fragments can create sharp edges that may cause deep cuts. Wearing heavy-duty gloves provides necessary protection against these risks.

Electronics

Industrial magnets produce strong magnetic fields that can interfere with or permanently damage electronic devices and data storage systems. Caution should be exercised when working near computers, smartphones, hard drives, and other sensitive equipment to prevent unintended malfunctions or data loss.

Pacemakers

As electronic medical devices, pacemakers are highly susceptible to magnetic interference. Industrial magnets can disrupt their operation, posing life-threatening risks. Individuals with pacemakers or other magnet-sensitive medical implants should avoid working with strong magnets unless cleared by a medical professional.

Allergies

Some individuals experience allergic reactions to the component metals found in industrial magnets. Direct skin contact or inhalation of dust from machining or handling magnets can trigger allergic responses, making it important to be aware of potential risks and take necessary precautions.

Navigation

High-powered magnets can interfere with navigational instruments, including GPS systems and compasses. When traveling with industrial magnets, special precautions should be taken to prevent navigation disruptions.

Transport

Shipping powerful magnets requires careful planning to ensure they do not interfere with transportation equipment or adhere to metal surfaces within shipping containers. Proper shielding and packaging methods should be used to prevent unintended interactions during transit.

Care of Industrial Magnets

Inspection protocols for industrial magnets vary depending on their specific application. While all magnets perform optimally when cleaned and decontaminated regularly, the extent of degradation and the necessary frequency of maintenance should be determined based on usage conditions.

Magnets responsible for holding or lifting heavy loads should undergo routine testing to prevent unexpected failures that could result in dropped materials or workplace hazards. If there is any uncertainty about a magnet’s functionality, manufacturers can provide testing services or recommend suitable replacements.

Industrial Magnet Compliance and Standards

Given the vast range of applications for industrial magnets, compliance requirements and industry standards are highly specific to each use case. Conducting thorough research on the relevant standards for a particular application simplifies the manufacturing process for custom magnets, ensuring regulatory adherence and optimal performance. If compliance requirements remain unclear, manufacturers can offer guidance to ensure magnets meet necessary specifications.

Regardless of the application, general safety precautions must always be observed, particularly when handling powerful rare earth magnets, superconductors, and electromagnets, as their intense magnetic fields present unique operational risks.

Choosing a Manufacturer for Industrial Magnets

Because of the many differences in industrial magnet applications, it can be difficult to identify a single “best” manufacturer in your area. Instead, you should look for a manufacturer most suited to your needs and expectations as a customer. Look for these traits:

Familiarity with Your Specific Need

First and foremost, you want an industrial magnet supplier familiar with the type of magnet you're using and the application you’ll be using it for. A supplier familiar with your needs and expectations can offer superior service, lower expenses, and fewer mistakes. Seek out references from similar businesses to yours or ones that have used magnets for similar applications.

Versatility

You want a manufacturer that can customize to your exact needs. That doesn't mean you should look for a manufacturer with a one-size-fits-all solution somewhat close to what you need. The best custom magnet fabricators will go the extra step to meet your specific needs and adjust as necessary when it comes to any unusual requests.

Transparency

You want to fully understand what you're getting for what you pay in every interaction with a vendor, supplier, or contractor. This holds as true with magnets as it does with anything else.

Schedule

Make sure you're working with magnet manufacturers or suppliers who can meet your scheduling needs. You don't want to end up halfway through a project only to find out you won't have the magnets necessary to proceed for weeks or months to come.

If you need help, you can refer to the convenient list of manufacturers listed at the top of this page.

Magnet Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

Magnets are materials that exert a noticeable force on different materials.

Magnets are materials that exert a noticeable force on different materials.

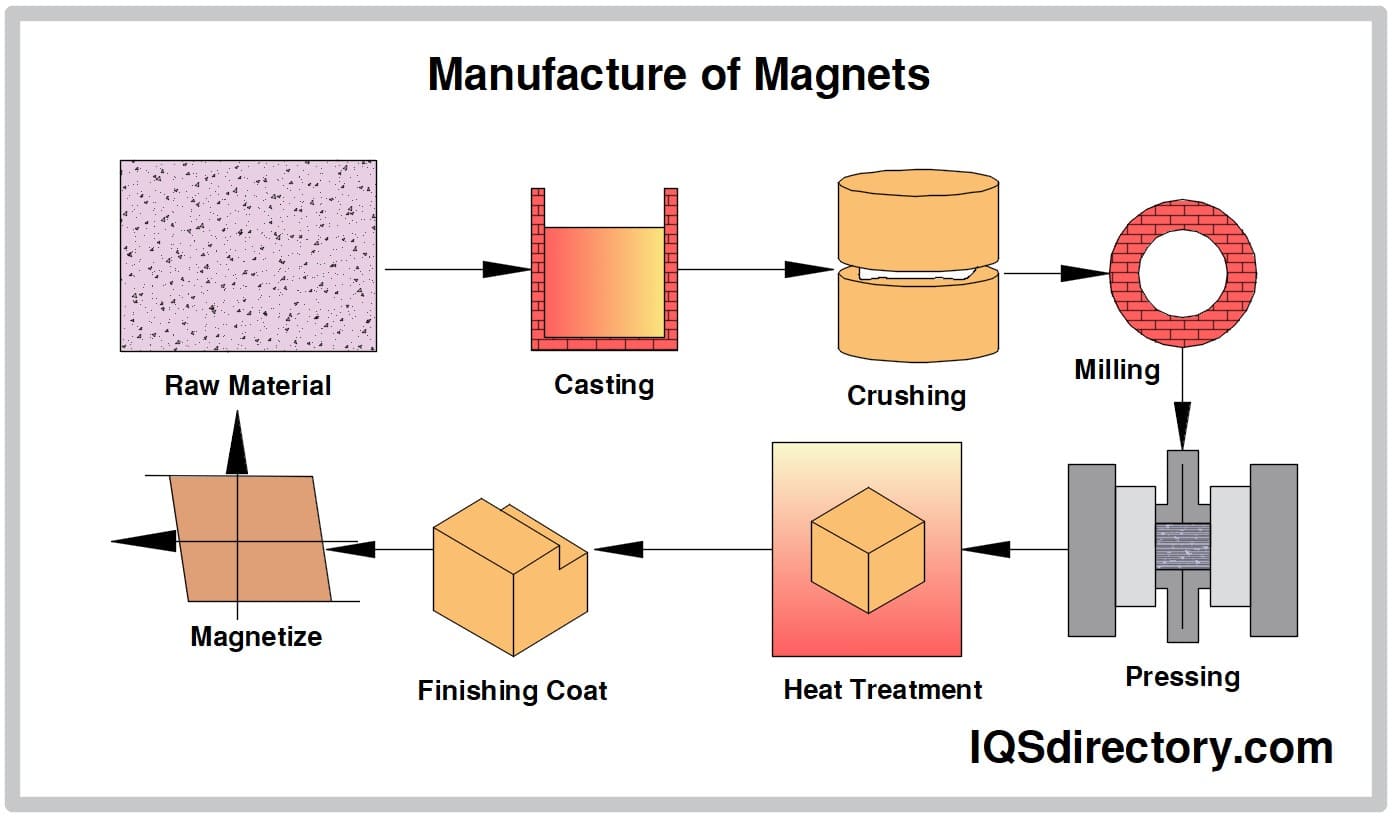

Since magnets are comprise different materials so the processes of manufacturing are different and unique.

Since magnets are comprise different materials so the processes of manufacturing are different and unique.

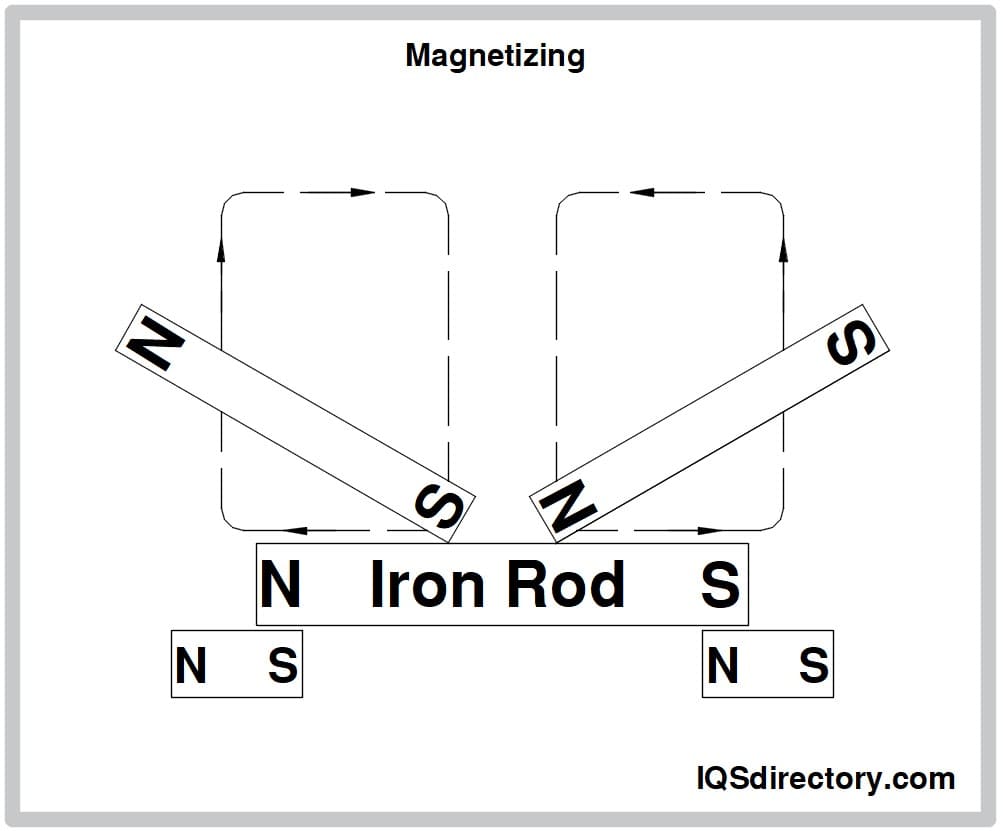

Following the finishing process and the manufacturing process, the magnet needs to be charged in order to produce an external magnetic field.

Following the finishing process and the manufacturing process, the magnet needs to be charged in order to produce an external magnetic field.

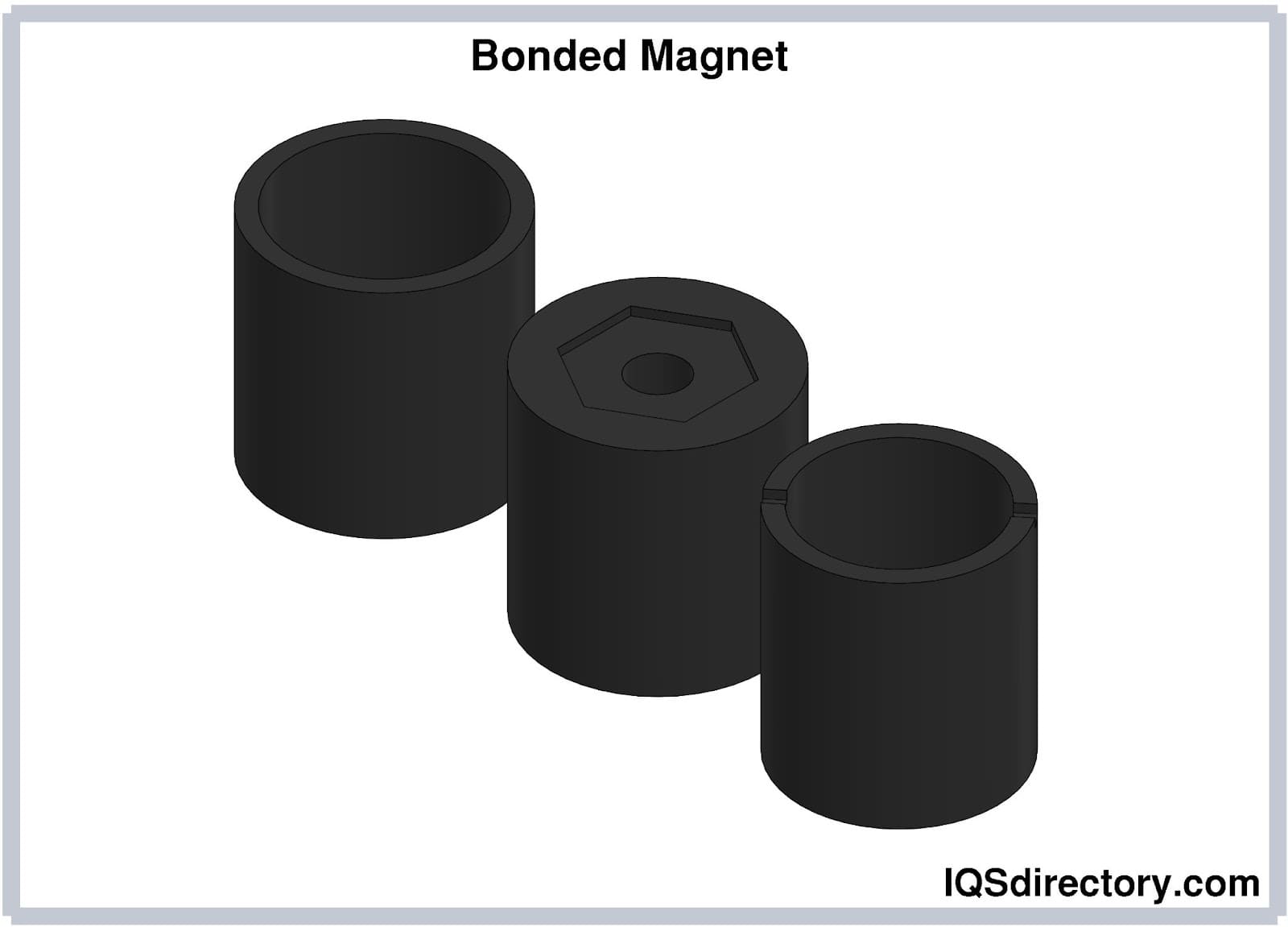

Bonded magnets have two main components a non-magnetic polymer and a hard magnetic powder which aims to be magnetically bonded no matter the materials.

Bonded magnets have two main components a non-magnetic polymer and a hard magnetic powder which aims to be magnetically bonded no matter the materials.

A very powerful magnet made of a ferromagnetic substance which is magnetized by an outward magnetic field which are capable of being magnetized over a long period of time.

A very powerful magnet made of a ferromagnetic substance which is magnetized by an outward magnetic field which are capable of being magnetized over a long period of time.

Magnetic separation involves separating a mixture of different components using a magnet to attract the magnetic materials.

Magnetic separation involves separating a mixture of different components using a magnet to attract the magnetic materials.

Magnet Types

-

Alnico Magnets

Sintered from a composite of aluminum, nickel, and cobalt, these magnets offer higher magnetic permanence and strength than all other non-rare earth magnets. Only rare earth magnets exceed their performance.

Bar Magnets

Narrow, rectangular pieces of ferromagnetic material or composite that generate a strong magnetic field, commonly used in educational and industrial applications.

Bipolar Assemblies

Ideal for part transference, welding alignments, and part-holding applications, these magnetic assemblies provide high heat resistance and an extended magnetic reach, making them valuable in demanding industrial environments.

Bonded Magnets

Created by combining thermoplastic or thermoelastomer resins with magnetic powders, these injection-molded, flexible magnets are well-suited for custom applications where rigid magnets would not offer the same versatility.

Ceramic Assemblies

Known for their resistance to demagnetization, these assemblies withstand exposure to electrical fields and vibration, making them ideal for welding, construction, and other environments where stability is critical. However, they have relatively low heat resistance.

Ceramic Magnets

Constructed from a mixture of strontium carbonate and iron oxide or other ceramic materials, these magnets offer an economical option for various industrial applications.

Custom Magnets

Manufactured to meet specific requirements, these magnets—whether sheet, alnico, neodymium, rare earth, or ceramic—are fabricated in specialized sizes, strengths, and densities for unique applications.

Electromagnets

Require an external electric current to generate a magnetic field, allowing for controlled activation and deactivation in industrial and electronic applications.

Ferrite Magnets

A cost-effective magnet type, ferrite magnets—also known as ceramic magnets—are widely used due to their durability and affordability. Though brittle, they maintain reliable performance in many applications.

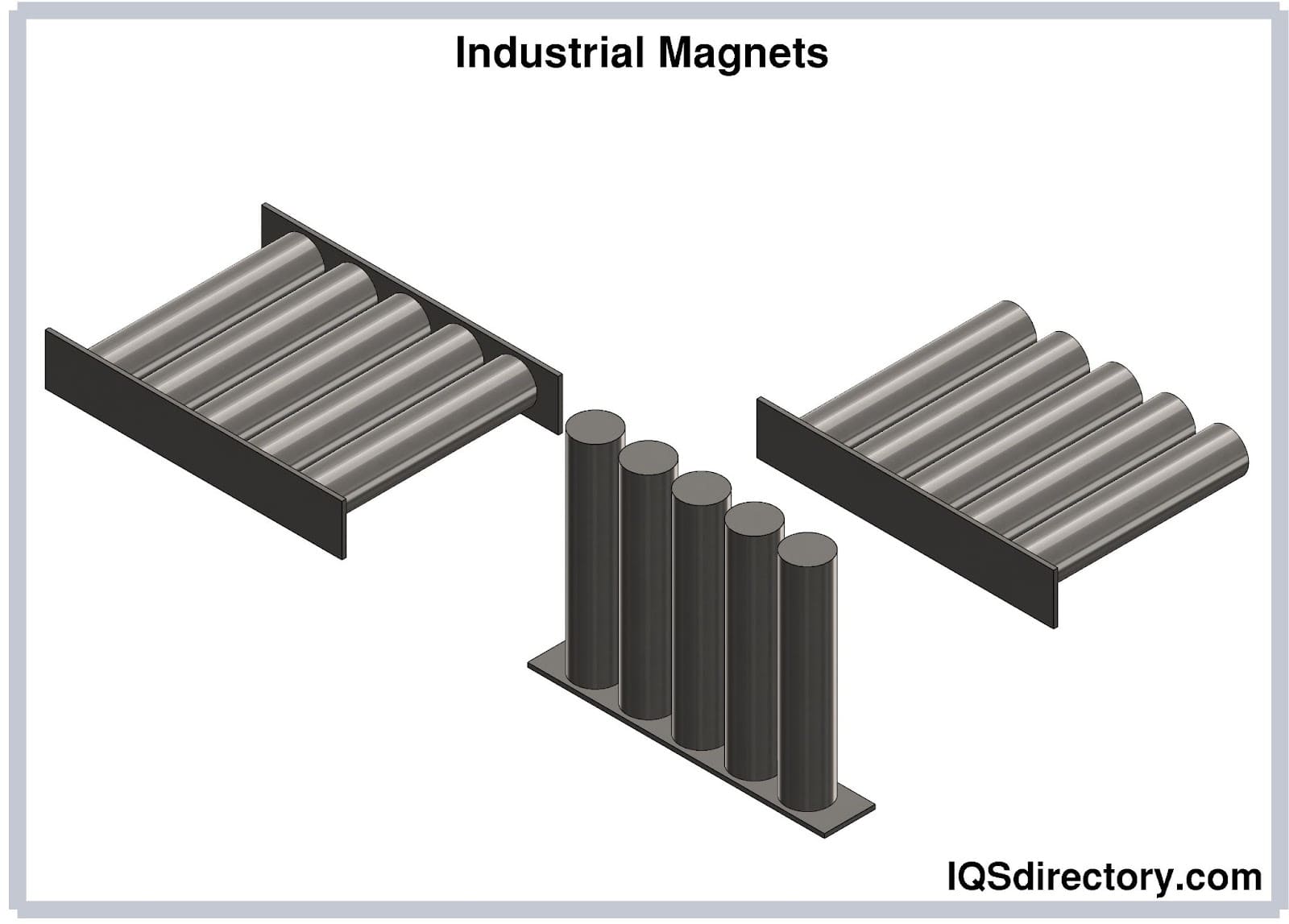

Industrial Magnets

Designed for heavy-duty industrial use, these powerful magnets are integral to lifting, separating, and securing ferrous materials.

Magnetic Assemblies

Composed of multiple magnets working together, these tools enhance the lifting, separation, and holding of metallic materials in manufacturing and processing industries.

Magnetic Strips

Thin, flexible magnetic rubber pieces, often featuring an adhesive backing for easy attachment to irregular or uneven surfaces.

Neodymium Magnets

Composed of neodymium, iron, and boron, these magnets—also called neodymium iron boron (NdFeB) magnets—are among the strongest permanent magnets available.

Permanent Magnets

Retain magnetism without requiring an external magnetic field, making them reliable for long-term applications without generating electricity or heat.

Rare Earth Assemblies

Offering the highest holding strength of all magnetic assemblies in a compact design, these assemblies are composed of neodymium and samarium cobalt magnets. However, they typically exhibit low heat resistance.

Rare Earth Magnets

Exceptionally powerful magnets composed of elements from the "Rare Earth" section of the periodic table. Their superior strength makes them essential in high-performance applications.

Sheet Magnets

Large, flat magnets designed to cover broad surfaces, often used in signage, industrial shielding, and flexible mounting solutions.

SmCo Magnets

Samarium cobalt (SmCo) magnets are a type of permanent magnet composed of rare earth metals samarium and cobalt. Known for their high-temperature resistance and stability, they are ideal for demanding applications requiring strong magnetic fields.

Magnet Terms

-

Alnico (Aluminum-Nickel-Cobalt)

A term referring to magnets composed of an aluminum, nickel, and cobalt alloy. These magnets offer medium to high magnetic strength and exhibit excellent resistance to heat-induced demagnetization.

Anisotropic

A magnetic property in which the magnet's orientation is predetermined during production by applying a magnetic field, resulting in a fixed direction of magnetism.

Assemblies

Systems or tools that incorporate magnets alongside other components, designed for tasks such as lifting, separating, or securely holding ferrous materials.

Badge Magnet

A magnet encased in a protective covering, used to attach identification badges to clothing without causing damage.

Bar

A long, narrow rectangular-shaped piece of ferromagnetic material or composite that generates a magnetic field.

Bipolar Assemblies

Heat-resistant magnetic assemblies with an extended magnetic reach, commonly used for alignment, holding applications, and industrial tasks requiring precision.

Bipole Electromagnet

An electromagnet configuration where the coil is positioned between two parallel steel plates that function as the north and south poles, enhancing magnetic efficiency.

Ceramic Magnet

A magnet composed of strontium carbonate and iron oxide, typically appearing in charcoal-colored disc, ring, block, cylinder, or arc shapes for use in motors and industrial applications.

Curie Temperature

The threshold temperature at which a magnet begins to lose its magnetic properties upon exposure to heat.

Demagnetizer

A device that neutralizes magnetism in magnetic materials by applying an alternating electrical current.

Demagnetizing Force

External influences such as temperature fluctuations, shock, vibration, or electrical and magnetic currents that reduce or eliminate a magnet's strength.

Ferrite Magnet

A widely used, low-cost magnet that is brittle yet resilient, offering good resistance to demagnetization, high-temperature stability, and superior corrosion resistance.

Ferrous Material

Any material that contains iron and is naturally attracted to a magnetic field.

Flexible Magnets

A magnet produced by combining ferrite powder with rubber polymer resin, shaped through extrusion or rolling, and later magnetized and laminated with vinyl or adhesive. These are the most pliable and cost-effective permanent magnets available.

Flux

A measurement that quantifies the overall strength of a magnetic field in a given area.

Gauss

A unit of measurement used to indicate magnetic induction, representing the strength of a magnetic field.

Industrial Magnet

A magnet designed for large-scale projects involving the lifting, separating, or holding of substantial ferrous materials. These magnets are highly adaptable and can be customized for specific industrial applications.

Isotropic

A magnetic property where no fixed direction of magnetization exists, allowing isotropic (non-oriented) magnets to be magnetized in any direction.

Lifting Magnet

A magnet integrated into a lifting system, used to transport ferrous materials such as bundled rods, scrap metal, or heavy metal blocks without the need for mechanical clamps.

Magnetic Field

The region around a magnet where the force of magnetism is exerted, with the strongest intensity concentrated at the North and South poles.

Magnetic Flux

A measurement of the strength of a magnet’s field, representing the rate at which magnetic energy moves through a given space.

Magnetic Induction

The process by which an object becomes magnetized due to the influence of an external magnetic field.

Magnetic Orientation

The directional alignment of a magnet, determined during its manufacturing process by exposure to a controlled magnetic field.

Magnetic Pole

A region within a magnet where magnetic flux is most concentrated. The strongest points of attraction or repulsion are found at the North and South poles.

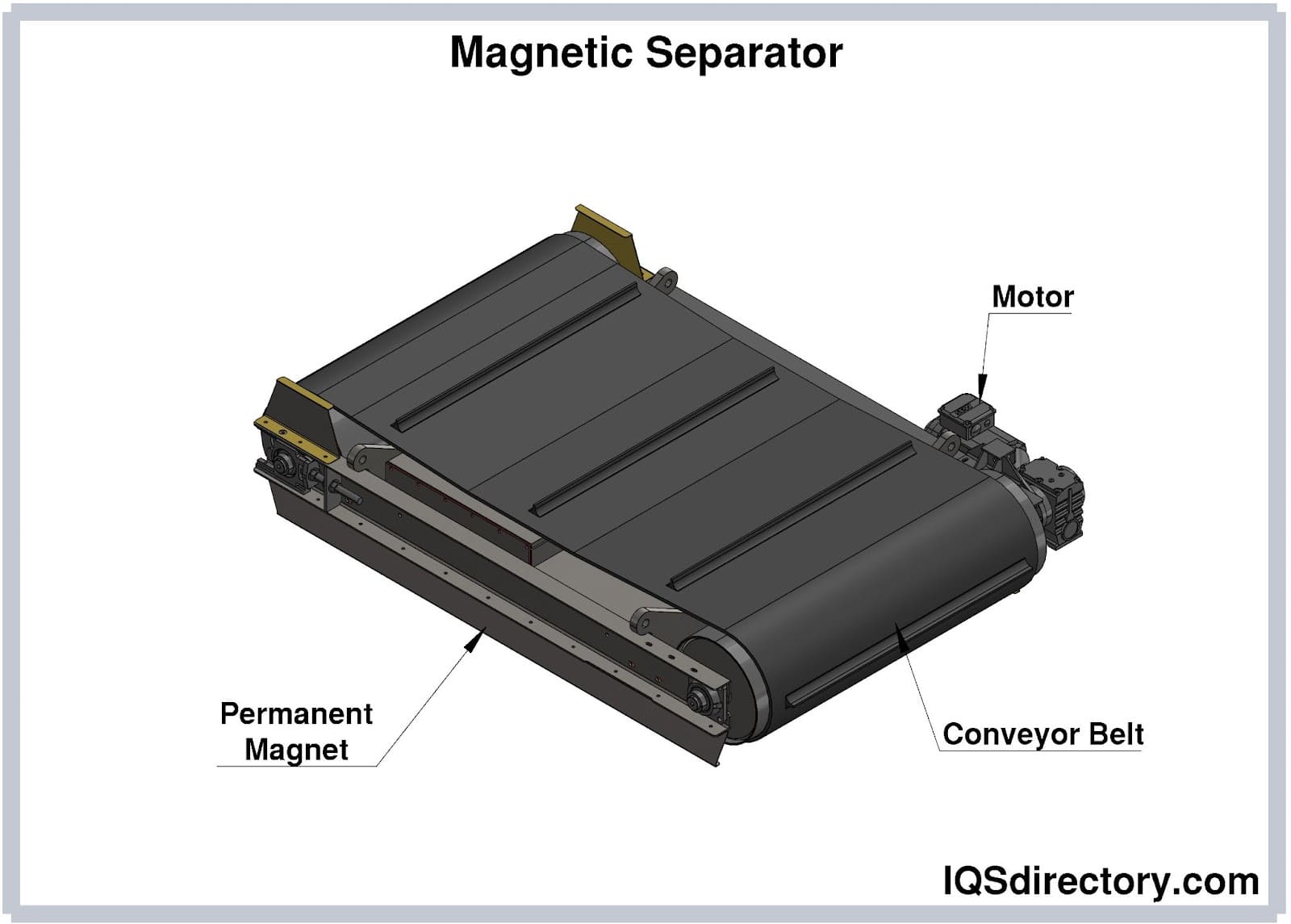

Magnetic Separators

Devices used to extract ferrous contaminants from materials, preventing damage to machinery and ensuring product purity.

Maxwell

A unit of measurement that quantifies magnetic flux, indicating the total magnetic field strength.

Neodymium Magnet

A rare earth magnet composed of neodymium, iron, and boron, offering superior strength at a smaller size and lower cost compared to most other magnets.

Oersted (Oe)

A unit used to measure the intensity of a magnetic field.

Permanent Magnet

A magnet that retains its magnetism indefinitely, even after being removed from an external magnetic field.

Rotary Magnetic Sweeper

A rolling device designed to collect metallic debris, preventing workplace hazards. The built-in release mechanism allows for safe disposal of collected metal fragments without direct handling.

Sheet Magnets

Large, flat magnets designed to cover broad surfaces, commonly used in signage and industrial applications.

Strips

Thin, flexible magnetic materials, often featuring adhesive backing for attachment to irregular or uneven surfaces.